In this case report, we bring to light a unique case of interval necrotizing pancreatitis -- a rare and potentially life-threatening complication of splenic artery embolization (SAE). We explore its risk factors and pathophysiology, and discuss the importance of early recognition, treatment, and patient education.

Introduction

SAE is safe and effective; therefore, it is more frequently employed in the nonoperative management of splenic trauma. Currently, the literature has few reports of necrotizing pancreatitis following SAE, and all reported cases have resulted in the need for surgical intervention or in life-threatening multiorgan dysfunction requiring a prolonged hospital stay.

Our report attempts to highlight the risk factors, pathophysiology, and importance of early recognition of necrotizing pancreatitis given its significant morbidity and mortality.

This case report was reviewed by the local institutional review board, and the need for informed consent was waived.

Case

An 81-year-old man was brought to a level I trauma center by emergency medical services as the restrained driver of a motor vehicle accident. On admission, he was hypertensive with a blood pressure of 184/99 mmHg and tachycardic with a heart rate of 109 beats per minute. His tachycardia was responsive to fluid boluses.

After initial resuscitation and focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST), he underwent a CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis that revealed a 1.4-cm grade III splenic laceration near the anterior lip associated with a focus of contrast extravasation. The exam also revealed an associated subcapsular hematoma larger than 50% of the surface area of the spleen, with hemorrhage tracking along the left paracolic gutter into the pelvis (figures 1A and 1B). The pancreas appeared unremarkable on this CT (figure 2).

Figures 1A and 1B: Axial and frontal views of CT of the abdomen with IV contrast show a focus of active extravasation within the spleen (above) associated with a large subcapsular hematoma (below). All images courtesy of Dr. Shruthi Suresh et al.

Figures 1A and 1B: Axial and frontal views of CT of the abdomen with IV contrast show a focus of active extravasation within the spleen (above) associated with a large subcapsular hematoma (below). All images courtesy of Dr. Shruthi Suresh et al. Figure 2: Axial view of CT of the abdomen demonstrates unremarkable appearance of the pancreas on arrival (white arrow).

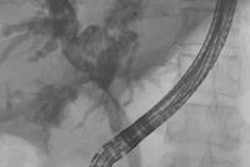

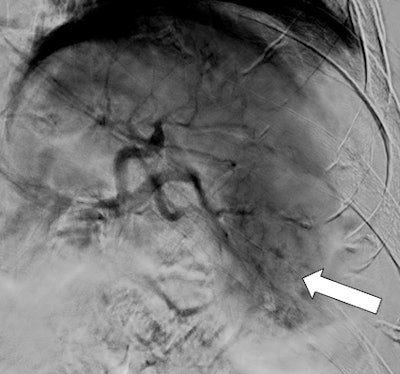

Figure 2: Axial view of CT of the abdomen demonstrates unremarkable appearance of the pancreas on arrival (white arrow).Splenic arteriogram demonstrated parenchymal injury and active extravasation, which corresponded with the CT, with identifiable contrast extravasation (figure 3A). In a location distal to the dorsal pancreatic artery, SAE was performed utilizing 0.035- and 0.018-inch coils.

Figures 3A and 3B: Splenic arteriogram demonstrates diffuse injury at the inferior pole of the spleen (above with extravasation). Coils were deployed distally to the dorsal pancreatic artery (black arrow). Postembolization arteriogram shows stasis of blood flow in the mid and distal splenic artery (below).

Figures 3A and 3B: Splenic arteriogram demonstrates diffuse injury at the inferior pole of the spleen (above with extravasation). Coils were deployed distally to the dorsal pancreatic artery (black arrow). Postembolization arteriogram shows stasis of blood flow in the mid and distal splenic artery (below).More than 35 coils were used to reach stasis because the splenic artery was hypertrophic with a very robust flow. Postembolization control arteriogram was performed and confirmed stasis of flow within the mid and distal splenic artery (figure 3B). The patient's hemoglobin stabilized; he clinically improved and was subsequently discharged.

The patient was readmitted two weeks later for fever, abdominal discomfort, and early satiety. On arrival, he was febrile at 38° C and had a pulse of 102 beats per minute, respirations of 25 breaths per minute, leukocytosis of 12,100 white blood cells (WBCs), and lipase of 125 UI-1. He underwent CT scans with IV contrast of the abdomen and pelvis that showed marked mesenteric fat stranding and an acute necrotic collection measuring 4.7 x 13.1 cm within the pancreatic body and tail.

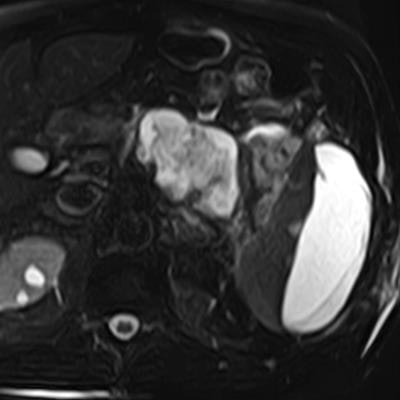

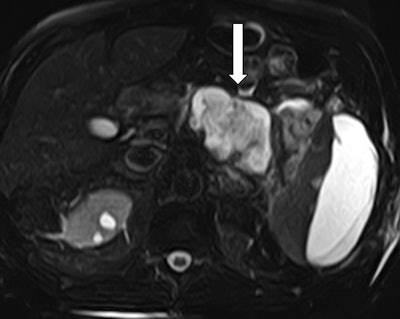

A provisional diagnosis of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) was made, after which blood cultures were obtained, and broad-spectrum antibiotics were started and then stopped in 24 hours due to negative blood cultures. MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) of the abdomen confirmed a necrotic collection involving most of the pancreatic body and tail (figure 4). The pancreatic duct was encompassed by the collection and difficult to appreciate.

Figure 4: MRCP confirms an acute necrotic collection. T2-weighted sequence of an abdominal MRI demonstrates involvement of the pancreatic body and tail. The pancreatic duct is obliterated by the collection and cannot be appreciated.

Figure 4: MRCP confirms an acute necrotic collection. T2-weighted sequence of an abdominal MRI demonstrates involvement of the pancreatic body and tail. The pancreatic duct is obliterated by the collection and cannot be appreciated.Over the course of the following week, our patient's WBCs and lipase normalized, and he was discharged home with a two-week follow-up CT of the abdomen.

Discussion

Of all blunt abdominal trauma, the spleen is one of the most frequently afflicted solid organs.1 The last decade has seen a rise in nonoperative management of hemodynamically stable blunt splenic injury with adjunctive use of splenic artery embolization due to a higher splenic salvage rate2-5 and a lower rate of early infectious complications.6 SAE, in fact, has been shown to be an independent predictor of spleen salvage in patients with high-grade splenic injuries or low-grade injuries with active extravasation, hemoperitoneum, or pseudoaneurysm seen on angiography.3

Considering that SAE has become commonplace in many institutions involved with the management of blunt splenic injuries, complications including rebleeding, splenic infarction, splenic abscess, paralytic ileus, and pleural effusions7 have been well described in the literature. Nevertheless, over the last two decades there have only been two case reports with a total of three documented patients that have developed acute necrotizing pancreatitis8-9 following SAE.

These case reports attribute central coil placement in particularly tortuous splenic arteries and inadvertent extensive SAE as causes without any discussion of risk factors that may contribute to hypoxic injury. Two of the three patients previously reported to have experienced this complication underwent a splenectomy with distal pancreatectomy; the third patient, who was medically managed, developed significant atelectasis and paralytic ileus and had a prolonged hospital stay.8-9

Our patient was managed according to the spleen trauma management algorithm for adult patients and underwent SAE for splenic injury with active extravasation seen on CT abdomen scans with IV contrast and splenic artery angiography. Care was taken to avoid the dorsal pancreatic artery as seen in figure 3; however, more than 35 coils were used to bring about stasis of blood.

The rich anastomotic blood supply between branches of the celiac artery, splenic artery, and superior mesenteric is likely why pancreatic necrosis is such a rare complication of SAE. Previous reports of necrotizing pancreatitis involving the tail of the pancreas were explained by poor distal blood supply or inadvertent extensive SAE. In our case, however, despite extensive embolization of the splenic artery, care was taken to avoid blockage of the dorsal pancreatic artery to preserve collateral blood supply to the body.

This indicates that ischemic damage was likely the result of poor or impaired collateral perfusion -- possibly a result of hypotension, hypoxia, atherosclerotic disease, or a combination thereof. Inadvertent extensive embolization of smaller supplying branches superimposed on poor blood supply likely added to the pancreatic ischemia.

Important factors to optimize blood supply to the pancreas after SAE include avoiding episodes of hypotension (providing aggressive resuscitation) and avoiding episodes of hypoxia (providing supplemental oxygen and treating the exacerbating factors). Decreasing the number of coils deployed may also reduce the risk of inadvertent embolization of collateral supply, though this may be challenging to do with diffuse splenic injury, as seen in our case. It may also be beneficial to avoid medications that induce pancreatitis through other mechanisms, negating insult to pre-existing injury.

While it is possible that the cause of necrotizing pancreatitis in our patient was a direct result of his midline injury (impact), we feel this is less likely considering the initial CT scan showed no identifiable injury to the pancreas. Compared with the previously reported cases in which necrotizing pancreatitis developed acutely, our patient is unique in that he developed necrotizing pancreatitis two weeks after his initial presentation.

It would therefore stand to reason that as opposed to a presentation of acute necrotizing pancreatitis (which would have occurred within a few days) secondary to complete occlusion of the major blood supply to the body and tail of the pancreas, our patient had a subacute presentation due to the aforementioned risk factors contributing to hypoxic injury.

Conclusion

Splenic artery embolization has become an integral component in the nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury. It is important to educate patients and physicians -- not only on common complications but also rare, life-threatening complications such as necrotizing pancreatitis, especially when such episodes can present subacutely. Additionally, minimizing episodes of hypotension, hypoxia, and the number of coils utilized for embolization may help avoid this rare but deleterious complication.

Drs. Shruthi Suresh, Sarah Bashaw, Ammar Hashmi, and Susan Baro are from the department of general surgery in the division of trauma surgery, and Drs. Jeffrey Ortiz and Benjamin Wilson are from the department of radiology in the division of interventional radiology at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, PA.

References

- Ledbetter S, Smithuis R. Acute abdomen - Role of CT in trauma. Radiology Assistant website. http://www.radiologyassistant.nl/en/p466181ff61073/acute-abdomen-role-of-ct-in-trauma.html. August 2, 2007. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Cinquantini F, Simonini E, Di Saverio S, et al. Non-surgical management of blunt splenic trauma: A comparative analysis of non-operative management and splenic artery embolization-experience from a European trauma center. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41(9):1324-1332.

- Banerjee A, Duane TM, Wilson SP, et al. Trauma center variation in splenic artery embolization and spleen salvage: A multicenter analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(1):69-74; discussion 74-75.

- Crichton JCI, Naidoo K, Yet B, Brundage SI, Perkins Z. The role of splenic angioembolization as an adjunct to nonoperative management of blunt splenic injuries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(5):934-943.

- Tugnoli G, Bianchi E, Biscardi A, et al. Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury in adults: There is (still) a long way to go. The results of the Bologna-Maggiore Hospital trauma center experience and development of a clinical algorithm. Surg Today. 2015;45(10):1210-1217.

- Aiolfi A, Inaba K, Strumwasser A, et al. Splenic artery embolization versus splenectomy: Analysis for early in-hospital infectious complications and outcomes. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(3):356-360.

- Madoff DC, Denys A Wallace MJ. Splenic arterial interventions: anatomy, indications, technical considerations, and potential complications. Radiographics. 2005;25(suppl 1):S191-S211.

- Paul DB, Opalek JM. Proximal splenic arterial embolization may also result in pancreatic necrosis. J Trauma. 2011;71(1):268-269.

- Hamers RL, Van Den Berg FG, Groeneveld AB. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis following inadvertent extensive splenic artery embolisation for trauma. Br J Radiol. 2009;82(973):e11-e14.

- Thoeni RF. The revised Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis: Its importance for the radiologist and its effect on treatment. Radiology. 2012;262(3):751-764.