Interventional retrieval of fractured portacath fragment with cardiac migration

Abstract

Portacaths are commonly indicated for long-term administration of parenteral medications. We report a case of successful interventional retrieval of a fractured portacath fragment that has migrated into the right ventricle. This is rather an unusual complication that, at times, can be life-threatening, with the mortality rate exceeding 60%. Interventional endovascular techniques remain so far the preferred method of management, with the GooseNeck loop snare having the highest success rate.

Introduction

A portacath is a tunneled implantable venous access device that consists of a port and a catheter attached to it. The port is implanted in the chest wall or the arm, and the tip of the catheter is placed in the superior vena cava or the right atrium. Portacaths are commonly indicated for long-term parenteral administration of medications, such as antibiotics in patients with cystic fibrosis and chemotherapy in patients with malignancy.1

The most frequent complications are pneumothorax, deep vein thrombosis, and infection.2,3 However, mechanical complications including fracture, dislodgement, migration, and leak are relatively uncommon. We report a case of portacath fracture with migration of the proximal fragment of the catheter into the right ventricle.

Case

A 32-year-old female patient, with known case of breast cancer (invasive ductal carcinoma), was referred to interventional suite for removal of a retained fragment of the fractured portacath that had migrated to the right ventricle. The patient had a bilateral mastectomy with right axillary lymph node dissection and had completed chemotherapy. The portacath was placed in the left subclavian vein and remained there for about three years and four months.

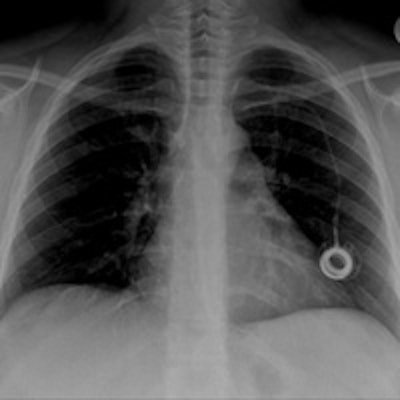

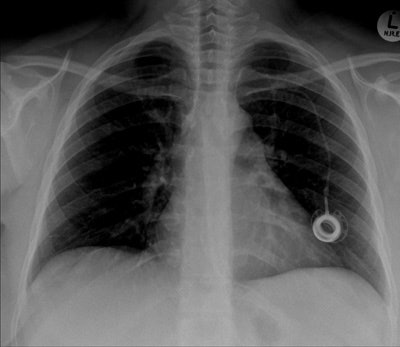

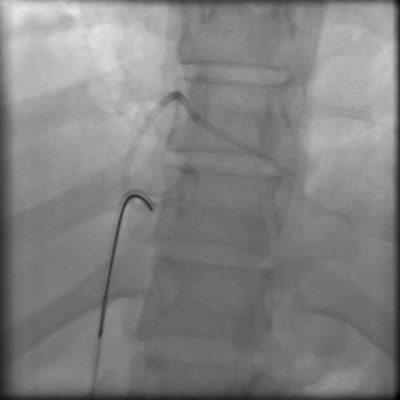

Chest radiograph of a 32-year-old woman shows cardiac migration of the proximal fragment of a fractured portacath. All images courtesy of Drs. Jamal Al Deen Alkoteesh and Maysam T. Abu Sa'a.

Chest radiograph of a 32-year-old woman shows cardiac migration of the proximal fragment of a fractured portacath. All images courtesy of Drs. Jamal Al Deen Alkoteesh and Maysam T. Abu Sa'a.The portacath fracture was incidentally discovered on chest radiograph, which showed cardiac migration of the proximal fragment. Echocardiography was performed and showed preserved left ventricular function with ejection fraction of about 50% to 55%. No regional wall motion abnormalities seen. Linear shadow was seen on echocardiography, representing the retained fragment.

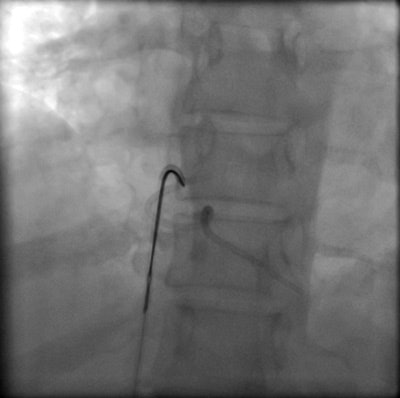

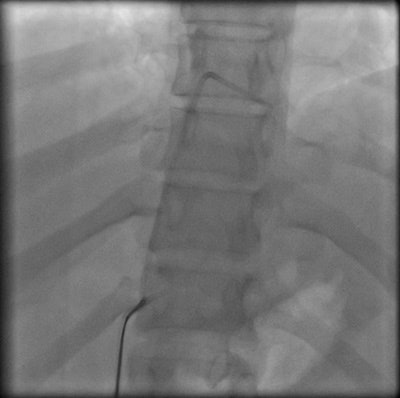

Percutaneous retrieval of the retained fragment of the fractured portacath catheter was successfully accomplished on the second attempt. Following prepping of the right groin, the right femoral vein was punctured and an 8 French sheath was inserted. Selective catheterization of the right ventricle was performed using a 6 French catheter. A 25-mm snare was used to capture the migrated retained fragment. It was then removed successfully without immediate complications.

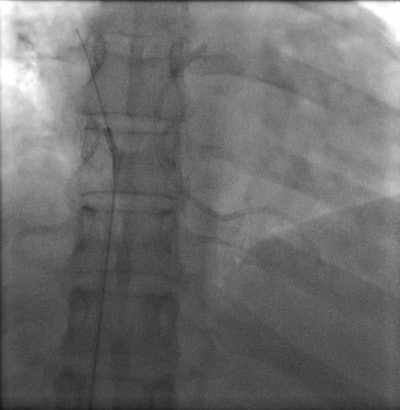

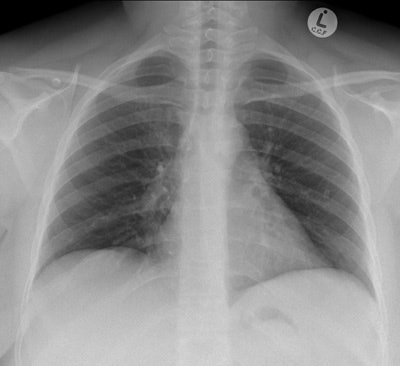

The postoperative radiograph showed no residual fragments.

Postoperative chest radiograph.

Postoperative chest radiograph.Discussion

Portacath fracture with fragment migration is a rare complication with an estimated incidence of about 0.3% to 2.9% in adults and 1.4% to 3.6% in children.4,5 It was first reported in 1954 by Turner and Sommers.6 The most common location of the portacath fracture is the anastomosis site between the port and the catheter.7

The cause of portacath fracture is unknown. Compression of the catheter between the first rib and the clavicle by the costoclavicular ligament and the subclavius muscle was described in literature as a possible explanation of subclavian portacath fracture, and this leads to what is known as "pinch off syndrome" 8,9; nevertheless, this can't explain fracture of portacaths that are inserted in other veins such as the internal jugular vein.10

Catheter migration is rather an unusual complication with the internal jugular vein being the most common site of migration.11 It may be caused by increased intrathoracic pressure and physical movement, yet in most cases the cause is unknown.10 Male gender and lung cancer were recently identified to be probable risk factors.10 Moreover, shallow catheter tip location and venous port type may play a role.10-12

In this case, we presented a far less common complication of portacath with fracture of the catheter and migration of the proximal part into the right ventricle. This complication is usually found incidentally in the chest radiographs of asymptomatic patients.13 Nonetheless, chest wall swelling around the port and shoulder pain are the most common findings in symptomatic patients. In addition, patients occasionally present with cough, chest pain, and palpitation.14 Malfunction of the portacath prompted further workup in many cases and sometimes is the first sign of portacath fracture.15

Cardiac migration of a fractured portacath is associated with potentially serious complications, and at times they could be life-threatening. These include sepsis, pulmonary thromboembolism, ventricular tachydysrhythmia, cardiac arrest, and cardiac perforation.16,17 It is reported that the mortality rate may reach as high as 60% in some patients with the cause of death being one or more of the following: septic endocarditis, arrhythmias with cardiac failure, inferior vena cava thrombosis leading to pulmonary embolism, and cardiac wall necrosis.18

Percutaneous transcatheter retrieval of the portacath fractured fragment by interventional endovascular techniques is the preferred method of management. GooseNeck loop snare, which we have used in this case, is the most popular device used with a success rate of about 90%.4 If the fractured fragment that has migrated to the heart is not detected and removed early, it becomes endothelialized and may require surgical removal.10

Conclusion

Cardiac migration of a fractured portacath is a potentially life-threatening complication; hence, careful follow-up of patients with indwelling portacaths, early detection of complications, and prompt management are recommended. Interventional endovascular techniques using the GooseNeck loop snare remain the preferred method of management.

Drs. Jamal Al Deen Alkoteesh and Maysam T. Abu Sa'a are from the department of interventional radiology at Tawam Hospital in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates.

References

- Ananthakrishnan G, McDonald R, Moss J, Kasthuri R. Central venous access port devices -- a pictorial review of common complications from the interventional radiology perspective. J Vasc Access. 2012;13(1):9-15.

- Yildizeli B, Laçin T, Batirel HF, Yüksel M. Complications and management of long-term central venous access catheters and ports. J Vasc Access. 2004;5(4):174-178.

- Poorter RL Lauw FN, Bemelman WA, Bakker PJ, Taat CW, Veenhof CH. Complications of an implantable venous access device (Port-a-Cath) during intermittent continuous infusion of chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A(13): 2262-2266.

- önal B, Coşkun B, Karabulut R, Ilgıt ET, Türkyilmaz Z, Sönmez K. Interventional radiological retrieval of embolized vascular access device fragments. Diag Interv Radiol. 2012;18(1):87-91.

- Kim OK, Kim SH, Kim JB, et al. Transluminal removal of a fractured and embolized indwelling central venous catheter in the pulmonary artery. Korean J Intern Med. 2006;21(3):187-190.

- Turner DD, Sommers SC. Accidental passage of a polyethylene catheter from cubital vein to right atrium. N Engl J Med. 1954;251(18):744-745.

- Lin CH, Wu HS, Chan DC, Hsieh CB, Huang MH, Yu JC. The mechanisms of failure of totally implantable central venous access system: Analysis of 73 cases with fracture of catheter. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36(1):100-103.

- Aitken DR, Minton JP. The "pinch-off sign": A warning of impending problems with permanent subclavian catheters. Am J Surg. 1984;148(5):633-636.

- Andris DA, Krzywda EA, Schulte W, Ausman R, Quebbeman EJ. Pinch-off syndrome: A rare etiology for central venous catheter occlusion. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1994;18(6):531-533.

- Funaki B. Central venous access: A primer for the diagnostic radiologist. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179(2):309-318.

- Fan WC, Wu CH, Tsai MJ, et al. Risk factors for venous port migration in a single institute in Taiwan. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12(15):1186/1477-7819.

- Wu CY, Fu JY, Feng PH, et al. Rsk factors and possible mechanisms of intravenous port catheter migration. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44 (1):82-87.

- Sattari M, Kazory A, Phillips RA. Fracture and cardiac migration of an implanted venous catheter. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2003;2(4):532-533.

- Al Hindi S, Al-Saad K. Spontaneous migration of a central line catheter into the heart. Bahrain Medical Bulletin. 2007;29(3).

- Kock HJ, Pietsch M, Krause U, Wilke H, Eigler FW. Implantable vascular access systems: Experience in 1500 patients with totally implanted central venous port systems. World J Surg. 1998;22(1):12-16.

- Hsieh HJ, Lue KH, Chang BS, Kao CH, Liu SH, Kao PF. Port-A catheter fracture: A potential lethal iatrogenic complication identified on PET-CT. Ann Nucl Med Sci. 2009;22(1):47-51.

- Denny MA, Frank LR. Ventricular tachycardia secondary to Port-a-Cath fracture and embolization. J Emerg Med. 2003;24(1):29-34.

- Wu CY, Fu JY, Feng PH, et al. Catheter fracture of intravenous ports and its management. World J Surg. 2011;35(11):2403-2410.