The passing of celebrated news anchor Peter Jennings was a sad reminder, if any were needed, that lung cancer is usually still fatal -- if only because most diagnoses, Mr. Jennings' included, come too late for effective treatment.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) reports that more people are calling for information on quitting smoking since Jennings' death on August 8. Last week brought news of the death of actress Barbara Bel Geddes, of '80s TV show "Dallas" fame. And Dana Reeve, wife of the late actor Christopher Reeve and a nonsmoker, revealed her own lung cancer diagnosis. News of celebrities' battles with disease can be salutary, of course, when it encourages public awareness of prevention and screening issues.

Lung cancer's toll can hardly be overemphasized. The New York City-based ACS estimates that 172,570 new cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed in the U.S. this year, and an estimated 163,510 will die from the disease.

For those unable to escape a diagnosis, multidetector-row CT is offering much-needed hope by finding more cancers earlier. CT's rapidly advancing capabilities, aimed at catching more cancers while they're potentially curable, have been the driving force behind the growth of lung cancer screening trials over the past decade.

National Cancer Institute/SEER reports (1995-2000) peg the five-year survival rate for localized lung cancer at 49.4%, compared to just 2.1% when there are distant metastases. But only 20% of lung cancer patients are diagnosed while their disease is resectable, and many more die as a result of late diagnoses, researchers believe.

Thanks to better scanners, some lung screening trials are reporting positive results for a majority of the patients they scan. The question is what to do with the proliferation of solitary pulmonary nodules (SPN)? When should they be biopsied, resected, or followed up with serial CT? Should some subjects with diminutive "ditzels" simply head home and stop worrying? This question is complicated by the benign appearance of some malignant nodules and the malignant appearance of some benign lesions.

But these are exceptions to the rule that larger masses, and those with nonsolid components, are more likely malignant. And thoracic radiologists have more on their side than elaborate CT scanners. They've gained a wealth of experience with lung nodules that only the passage of time, prudent follow-up, and multiple clinical trials can teach.

In presentations at the recent International Symposium on Multidetector-Row CT in San Francisco, two thoracic imaging experts discussed the impact of the CT screening data becoming available, and offered advice on which nodules to biopsy, resect, follow, or even ignore.

Dr. Ella Kazerooni, professor and chief of thoracic imaging at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, discussed the evolving criteria for following and acting on lung nodules.

Dr. Anna Leung, professor of radiology and chief of thoracic imaging at Stanford University in California detailed some additional CT characteristics that can offer clues to the malignancy or benignity of detected nodules.

"Fast-evolving CT technology has produced exquisite image quality," Kazerooni said in her talk. "In thoracic imaging it's also made for the problem of increased finding of multiple small pulmonary nodules."

"Improvements in volumetric acquisition have eliminated the possibility of respiratory misregistration," noted Leung in hers. "Now that most of us do paging on our PACS stations we can easily differentiate between nodules and vessels, and the decreased vessel thickness enabled by fast scanners allows us to detect very small nodules, or see larger nodules on multiple sections."

Better scanners and more scanning mean many more nodules to interpret than in the past, Kazerooni said. Where early trials might have turned up suspicious lesions in 10% to 20% of patients, newer studies are finding far more.

"Up to 50% or sometimes higher of patients in these screening trials have had pulmonary nodules, a very small percentage of which turn out to be cancer," Kazerooni said.

Among the latest published results, Swenson et al from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, enrolled 1,520 subjects who underwent annual CT exams for five years. The researchers found 3,356 noncalcified lung nodules in 74% of their subjects. Sixty-eight lung cancers were eventually diagnosed (Radiology, April 2005, Vol. 235:1, pp. 259-265).

"How are we going to manage all these small pulmonary nodules?" Kazerooni asked. "Do we just ignore (them)? Do we send them for a PET scan or biopsy? Do we follow them, and if so, how often do we follow them?"

Radiologists worry most about small noncalcified nodules, which have a benign behavior, although not necessarily a benign etiology, in as many as 98% of patients, Kazerooni said. Such findings generally represent benign granulomas or healed infarcts, but they can also be small indolent carcinomas that don't grow during the patient's lifetime -- or alternatively, remain stable until patients undergo a change in their immune status.

In the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), aimed at determining if there is a mortality benefit from x-ray or CT lung screening, negative scans are defined as subjects with no detected nodules -- or subjects with nodules smaller than 4 mm, who go back into annual screening. Nodules 4-10 mm in size are followed up at six, 12, and 24 months, said Kazerooni, whose group is participating in the trial.

Previous studies have specified a three-month follow-up for nodules 4-10 mm, "but many people have backed off doing a three-month follow-up CT, because for small nodules it's very hard to appreciate if it actually changed, visually," Kazerooni said.

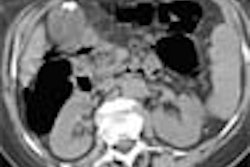

|

| The benign-appearing nodule on the left is malignant; the spiculated mass on the right is benign. All images courtesy of Dr. Ella Kazerooni. |

Small nodules hard to evaluate

"These (4-10 mm) nodules are usually too small for PET and too small for percutaneous biopsy," Kazerooni said. If, on the other hand, the nodule is new and 10 mm or larger, or growing and 7 mm or larger, further evaluation is recommended with either PET or contrast-enhanced HRCT, or further definitive diagnosis with either biopsy or resection.

"There are limitations in what we can do to diagnose small nodules," Leung noted. Contrast-enhanced studies aren't helpful for nodules smaller than about 5 mm in diameters, and PET resolution is around 7 mm. And although needle biopsy with VATS (video-assisted thoracic surgery) should be a very high-yield procedure, the difficulty lies in the localization of small lesions, Leung said.

"In order for patients to be eligible for VATS, the lesion must be located in the peripheral one-third of the lung," she said. Because of the difficulty of localizing small lesions, it is recommended that any lesion less than 1 cm that is going through a VATS procedure should have preoperative localization by some sort of guide wire."

The small ones can't quite be ignored, either

Other studies highlight the fact that small nodules aren't necessarily benign. The mean size of detected lung cancers in single-arm trials has ranged from about 1.5-2.5 cm in diameter, on average. But many subcentimeter nodules are included in these figures, and radiologists are concerned about the large number of diminutive cancers being detected, Kazerooni said.

For example, she said, in 2005 Swensen and colleagues reported that 9/27, or 34% of lung cancers detected, were in the subcentimeter range.

Sone and colleagues found that 6/23 (27%) of the cancers detected among their 5,483 participants were smaller than 1 cm in diameter (British Journal of Cancer, January 5, 2001, Vol. 84:1, pp. 25-32).

And ELCAP (I) authors Henschke and colleagues reported that 15/36, or 56% of all malignancies, were smaller than 1 cm (Cancer, July 2001, Vol. 92:1, pp. 153-159). Clearly these nodules can't be ignored entirely, Kazerooni said.

In 2001 members of the Rochester, MN-based Society of Thoracic Radiology were asked for their recommendations on dealing with "ditzels," or diminutive SPN 3-5 mm in diameter, Kazerooni said.

Among 157 respondents the most common recommendation (31% to 64% of the time) was short-term follow-up of unspecified length. The recommendations were less aggressive for lower-risk patients, such as those who had never smoked, and more aggressive in cases with a higher likelihood of malignancy, such as patients with a known cancer (American Journal of Roentgenology, June 2001, Vol. 176:6 pp. 1363-1369).

Smaller nodules were far less likely to be malignant according to the results of ELCAP II, which screened 2,897 subjects. Henschke and colleagues found zero cancers among 374 subjects whose largest detected nodule was less than 5 mm at baseline, Kazerooni noted. Yet the team found 14 cancers among 238 subjects (5.9%) whose largest nodule was 5-9 mm (Radiology, April 2004, Vol. 231:1, pp. 164-168).

"So the recommendation from (Dr.) Claudia Henschke and colleagues was for nodules less than 5 mm, follow-up ... less than one year is not warranted, and (subjects) would go back into annual screening," Kazerooni said. The team is recommending follow-up for nodules 5-9 mm in diameter.

Based on their results published in 2005, Swenson and colleagues from the Mayo Clinic are recommending annual screening for detected nodules smaller than 4 mm, 3-month follow-up for nodules 4-7 mm, and biopsy or PET for nodules larger than 7 mm.

Larger nodules more likely malignant

Leung noted a 1993 study by Gurney and colleagues that used Bayesian analysis to determine that nodule size was directly related to the probability of malignancy. The likelihood ratio of malignancy for nodules less than 1 cm, 1.2-2 cm, 2.1-3 cm, and greater than 3 cm was 0.52, 0.74, 3.7, and 5.2, respectively, she said (Radiology, February 1993, Vol. 186:2, pp. 415-422).

"However, what I want to point out is that missed cancers can occur not only from lack of detection, but a significant portion -- 41% -- based on errors of interpretation," Leung said, referencing two Japanese studies (Kakinuma et al, Radiology, July 1999, Vol. 212:1, pp. 61-66; and Li et al, Radiology, December 2002, Vol. 225:3 pp. 673-683).

Malignant lesions "are often misinterpreted as either related to granulomatous disease or a scar," Leung said.

Radiologists cannot be complacent about dismissing nodules just because they're small, Kazerooni noted. In two studies from Duke University, researchers examined patients with diagnosed stage T1 lung cancer to determine if tumor size correlated with survival (Patz et al, Chest, June 2000, Vol. 117:6, pp. 1,568-1,571; Heyneman et al, Cancer, December 15 2001, Vol. 92:12, pp. 3,051-3,055).

"There was no significant relationship in the stage distribution of cancer, or cancer survival, among patients with smaller tumors -- because small tumors can metastasize even before they manifest with large pulmonary masses," Kazerooni said. "So size may not be everything in lung cancer."

Suspicious criteria

Beyond size, a standard method that has evolved to classify nodules is related to their attenuation -- "Solid, nonsolid, and part-solid nodules ... that have components of both," Kazerooni said. "We know that nodules with a ground-glass or nonsolid component have a higher rate of malignancy than the solid nodules" (Likelihood of malignancy: Partly solid 63%, nonsolid 18%, solid 7%, Henschke et al, AJR, May 2002, Vol. 178:5, pp. 1053-1057).

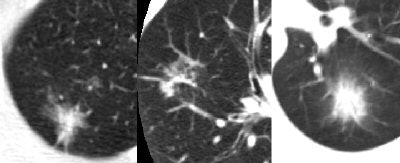

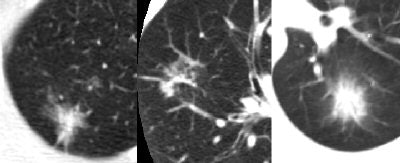

|

| Part-solid nodules, above, are far more likely to be malignant than either solid or nonsolid nodules. |

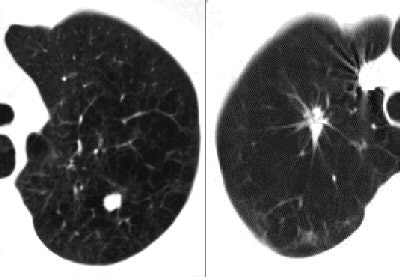

|

| Nonsolid nodules have a higher probability of malignancy than solid nodules, but a lower probability of malignancy than part-solid nodules. |

"We're all acquainted with accepted criteria for benign pulmonary nodules: fat, characteristic calcification, and what has been previously accepted -- size stability over two years," Leung said. "But as you've heard there are some very slow-growing indolent tumors that may appear stable over two years, but with longer periods of observation will ultimately grow, and prove to be low-grade malignancies."

Shape also appears to affect the probability of malignancy, Leung said -- flat lesions, for example, are more likely benign.

Researchers in Japan have found evidence that for solid lesions smaller than 1 cm, the presence of polygonal shape, lesions with concave margins, a 3D ratio greater than 1.78, and peripheral subpleural location are characteristics more commonly found in benign versus malignant lesions, she noted (Takashima et al, AJR, April 2003, Vol. 180:4, pp. 955-964; AJR, May 2003, Vol. 180:5, pp. 1,255-1,263).

"They defined 3D ratio as the maximum transverse dimension on an axial image divided by the maximum vertical dimension on a coronal reformation. And if that ratio was greater than 1.78 -- expressly what they're looking for are flat lesions -- then those lesions are more likely to be benign," Leung said.

Another frequently cited characteristic is the presence of intrapulmonary lymph nodes that occur along the subpleural lymphatic chain, typically below the carina, Leung said.

These benign findings manifest as solid lesions smaller than 15 mm, and within 15 mm of a pleural surface Leung noted. They can be round, oval, or lobulated with sharp margins, according to studies by Matsuki et al and Oshiro et al (Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography, September-October 2001, Vol. 25:5, pp. 753-756; July-August 2002, Vol. 26:4, pp. 553-557).

"Now that's all very interesting information to know, but clearly we cannot prospectively recognize an intrapulmonary lymph based on these nonspecific criteria," Leung added.

A feature more often associated with malignancy is the air bronchogram sign, she said, most commonly seen in bronchoalveolar-cell and other types of adenocarcinomas. The nodule margins may be smooth, or irregular and spiculated, but with an internal air bronchogram. It's helpful to make use of specific signs whenever possible to determine the best course of action for a particular patient, she advised.

Follow-up recommendations

"For nodules less than 4 mm, continue annual screening if you're involved in a screening trial," Kazerooni said. "But for patients with no known pulmonary neoplasm, no additional follow-up may be needed."

No follow-up recommendations are included in the radiology reports for nonsmokers with nodules 4 mm and smaller, and nodules from approximately 4-8 mm are followed-up at six, 12, and 24 months, "although there's still some concern, and maybe we should do a three-year follow-up CT," Kazerooni said. Nodules 8 mm and larger are big enough to act on with PET or percutaneous biopsy; these patients should not be put into a follow-up arm.

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

August 19, 2005

Related Reading

Lung PET rules when CT is equivocal, discordant, July 12, 2005

CT and PET screening useful in detecting early lung cancer, June 15, 2005

Emphysema alters CT appearance of benign nodules, May 4, 2005

More PET/CT lung masses seen with hardware-based fusion, April 26, 2005

CT screening detects early lung cancers, but mortality benefits unclear, March 17, 2005

CAD substantially improves MDCT's sensitivity in detecting lung nodules, January 12, 2005

Copyright © 2005 AuntMinnie.com