Individuals who were negative in their first round of virtual colonoscopy screening tend to stay that way at repeat screening five years later. The results are a positive sign that VC is a good way to detect significant lesions before they can advance to malignancies.

Among 451 negative screening subjects who came back for their regular repeat virtual colonoscopy exam (also known as CT colonography or CTC) five years later, 90% remained negative, and 1.8% were found to harbor advanced neoplasia, including one patient diagnosed with adenocarcinoma. The study from the University of Wisconsin was presented at the 2012 American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS) meeting in Vancouver.

"There's been a lot of debate about screening CTC; people have said that because we set our positive threshold for high-risk polyps at 6 mm, they would turn into cancers before we could screen them again," said Dr. David Kim in an interview with AuntMinnie.com.

"Other people have argued that flat polyps cannot be adequately seen by CTC and can be missed," he said. "In some populations, they're as prevalent as 10% of the screening population."

Critics charge that diminutive lesions or flat polyps that are not removed are "dangerous polyps that will turn into cancers before we can screen them again," Kim said. "If these claims are indeed correct -- that CTC performance is poor in certain types of lesions -- then we should see a high number of dangerous advanced neoplasia and even cancer at follow-up."

5-year outcomes

Kim, an associate professor of radiology at the University of Wisconsin (UW), said the study aimed to analyze five-year patient outcomes in screening subjects who were negative at their first screening to see how they fared.

The longevity and high volume of the CTC screening program at UW offers an opportunity to examine longer-term outcomes in people who were never examined with conventional optical colonoscopy.

Toward that end, the study by UW's Dr. James Boyum, Dr. Dustin Pooler, Kim, and Dr. Perry Pickhardt examined 2,196 consecutive individuals who underwent screening CTC over a 20-month interval.

In all, 1,906 individuals were told to come back for repeat screening in five years after a negative result at CTC. A negative result was classified as level C1 under the CT Colonography Reporting and Data System (C-RADS): no nondiminutive polyps at CTC. The mean age of study participants was about 57 years at initial screening and 62 years at repeat screening, Kim said.

No notices were sent to patients reminding them to return, and of the 1,906 patients, 451 (23.7%) came back five years later for routine screening.

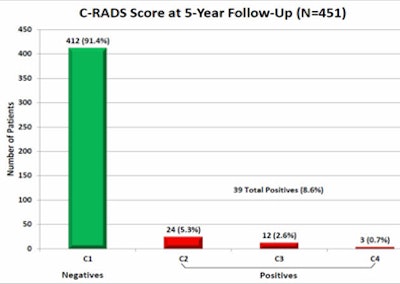

Of this group, 412 (91.4%) remained negative at follow-up (C-RADS C1). "The vast majority remained negative and went back into routine screening," Kim said.

Thirty-nine (8.6%) of the rescreened subjects had positive findings at follow-up, he said. Two-thirds of the findings were subcentimeter polyps, and the rest were 1 cm or larger.

|

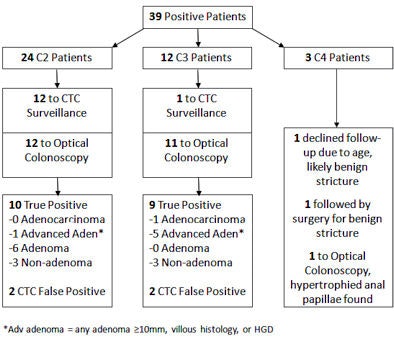

| Diagram shows results and management of 39 screening subjects, including 24 C-RADS 2 patients, 12 C-RADS 3 patients, and three C-RADS 4 patients. All images courtesy of Dr. David Kim and Dr. Dustin Pooler. |

In terms of categories, 5.3% (24/451) of the findings were C-RADS C2 (indeterminate finding, surveillance recommended); 2.7% (12/451) were C-RADS C3 (polyp, possible advanced adenoma, optical colonoscopy recommended); and 0.7% (3/451) were C-RADS C4 (colonic mass, likely malignant).

Twenty-four (61.5%) of the 39 positive patients underwent colonoscopy, while 15 (38.5%) opted for imaging surveillance. All patients with polyps 1 cm or larger went on to colonoscopy, while about half of those with subcentimeter lesions stayed in CTC surveillance, Kim said.

|

| C-RADS results for repeat VC at five years after a negative exam show a 91% negativity rate and advanced neoplasia in 0.7% of patients. |

Of those undergoing conventional colonoscopy, the advanced neoplasia incidence was 1.8%, with eight patients harboring nine lesions, including one adenocarcinoma. That patient had a T3N1 cancer that was resected; the patient went on to chemotherapy and is disease-free to date, Kim said.

Advanced status was determined by size (≥ 10 mm) for all but one lesion, Kim said. The one subcentimeter lesion met the criteria for advanced neoplasia with "tubulovillous histology -- not by high-grade dysplasia," he said.

A retrospective look at the patient's original CTC images five years ago showed that there was "something there," Kim said, but what turned out to be a flat lesion was interpreted as adherent stool.

"With what we know today, there's a good chance that [exam] would have been positive," he said, cautioning that no study is perfect, and the lesion could possibly have been missed prospectively even today.

Overall, three of the nine lesions, including the adenocarcinoma, could be seen in a review of the prior exams, Kim added.

The great majority of patients with negative initial CTC screenings remain negative at follow-up, but advanced neoplasia are present in a small percentage of patients at five years, underscoring the need for programmatic screening compliance, the authors concluded.

"The five-year screening interval for CTC is appropriate and safe," Kim said. "It's very likely safe for longer than that, but those data are just coming in." In fact, "clinically what has been happening is that most people have been coming back at six or seven years."

As a result, there are many more patients returning for CTC screening than the 451 five-year patients reported in the study. Whether or not the recommended screening interval can be extended is an interesting question, he said.

"My guess is that extending out to six or seven years is likely going to be safe -- the advanced neoplasia rate is very small at 1.8% -- and if you look back at the original prevalence in this cohort, it was over 3%."

The data suggest that screening is cutting that incidence by nearly half, so "screening at longer intervals is definitely something we're going to look into," he said.