Medical imaging exams such as x-ray and CT played a key role in managing patients who arrived in the minutes and hours after the Boston Marathon bombing last year, according to a study in the August issue of the American Journal of Roentgenology.

Three people were killed and more than 260 others were injured on April 15, 2013, when two pressure-cooker bombs packed with items such as nails and ball bearings detonated within a minute of each other at around 2:49 p.m. Survivors were treated at 27 local hospitals, with the most severely injured taken to level I trauma centers in Boston.

The task of diagnosing and treating patients was complicated by the arrival of so many people within such a short amount of time, according to the study's authors from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Brigham and Women's Hospital.

A typical day

It started as a typical day for lead author Dr. Ajay Singh, associate director in the division of emergency radiology at MGH, who was working at Brigham and Women's Faulkner Hospital. Singh was at the facility when staff was alerted about the explosions and warned that injured spectators and runners soon would arrive.

Because Faulkner is a small community hospital that received fewer patients with blast injuries, Singh went to MGH when his shift ended later that day to read images and help with the larger influx of more serious cases at MGH's trauma center.

For the current study, Singh and colleagues reviewed x-ray and contrast-enhanced CT exams from 43 patients to detail primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary blast injuries (AJR, August 2014, Vol. 203:2, pp. 235-239).

The 21 men and 22 women in the study ranged in age from 19 to 65 years (mean, 37.1 years). The first patient was imaged just 28 minutes after the initial blast. Seven patients presented for imaging within an hour, 22 arrived between 60 and 120 minutes after the blast, nine presented two to three hours later, and five arrived three to seven hours after the blast.

The researchers found no instances of lung injury or bowel perforation from the primary blast wave, but 14 patients had a perforated tympanic membrane (eardrum). Six of those patients subsequently underwent amputation of an extremity.

"The likely reason for the lack of pulmonary and bowel injury is believed to be the open space where the explosion occurred and the relatively smaller intensity of the blast," the authors wrote.

Secondary blast damage

Most of the physical damage came from the secondary blast wave after the initial explosion, Singh and colleagues found. These injuries are more common because the secondary blast wave includes flying debris, such as shrapnel fragments, traveling at high speed.

X-ray and CT showed a total of 189 shrapnel fragments in 32 (74%) of the 43 patients. Most of the objects (153, or 81%) were found in the soft tissues of the legs, thighs, and pelvis, while the remaining 19% were located above the pelvis or in the foot. The number of objects per patient ranged from one to 41 fragments.

Shrapnel from a secondary blast wave caused a fracture of the distal tibia and fibula in a patient's right leg. All images courtesy of AJR.

Shrapnel from a secondary blast wave caused a fracture of the distal tibia and fibula in a patient's right leg. All images courtesy of AJR.Clinicians also found a large variety of debris embedded in patents. There were 125 ball bearings, 44 metal fragments, 10 nails, one screw, and nine pieces of gravel or other foreign objects. In addition, 11 patients had fractures in areas including the foot, leg, thigh, hand, orbit, nose, and lumbar spine. Injuries to five of the patients were so severe that they required lower-limb amputations.

"Because the explosive devices were left on the ground, lower-extremity injuries were the most common, with five patients in our study group requiring lower-limb amputations as a result of their injuries," the authors wrote.

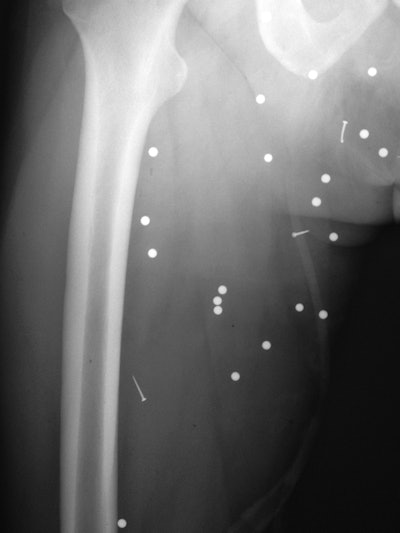

The secondary blast wave propelled multiple ball bearings and nails into the soft tissue of a patient's right thigh.

The secondary blast wave propelled multiple ball bearings and nails into the soft tissue of a patient's right thigh.Tertiary blast injuries result from falling or being thrown back by an explosion, according to the authors. In this category, right-sided lumbar transverse process and nasal bone fractures were found in two patients, along with a tibial shaft fracture in a third patient without any associated shrapnel or skin breech.

Quaternary blast wave injuries, which are caused by fire, chemicals, or other harmful agents, consisted of seven patients with burns.

"This study gives information regarding the imaging features to be expected in the event of a mass casualty caused by low-intensity blast," Singh told AuntMinnie.com by email. "The knowledge of the anatomical location and pattern of injuries from this event could be useful to the radiologists evaluating any similar event in the future."One potential bias in the study was the lack of more critically injured patients; those patients were taken to the operating room without imaging, according to Singh and colleagues.

"It is likely that a disproportionate number of these patients had secondary blast injuries leading to limb amputations, which were clinically obvious and therefore did not require initial imaging," they wrote.

The study also lacked patients who had minor injuries and did not require imaging. In addition, it is likely that patients who presented with missing limbs would have had additional fragments in their injured extremities, the authors speculated.

The extensive use of x-ray and CT for those injured in the Boston Marathon bombing reaffirms imaging's role in evaluating foreign bodies and skeletal trauma, Singh and colleagues concluded.