Body packers have become more sophisticated when it comes to concealing drugs or other contraband, but CT offers an effective way to identify illegal substances, according to a presentation delivered at the recent virtual RSNA 2020 meeting.

And although most contraband is detected at international airports or near country borders, the high prevalence of drug use in many cities and in the large U.S. prison population means that even "regular" radiologists should be aware of what to look for, presenter Dr. Barry Daly of the University of Maryland in Baltimore told session attendees.

"Radiology professionals must be aware of the spectrum of findings likely to be encountered [when it comes to body packing]," he said.

Sophisticated packaging

International smuggling of drugs through concealing them in the body was first noted in the early 1970s, Daly said. Since that time, the practice has been increasing, particularly after border surveillance was boosted following the September 11 attacks.

There are a number of ways that drug smugglers conceal contraband in their bodies, according to Daly: Body packers (i.e., "drug mules") may transport cocaine, heroin, ecstasy, and marijuana across borders in packets ingested into the gastrointestinal tract; body stuffers ingest smaller amounts of drugs to avoid imminent discovery or arrest; and body pushers hide drugs, weapons, or other contraband in the rectum or the vagina.

The standard imaging modality for identifying drugs or contraband hidden in the body has been x-ray, but manufacturing techniques for drug packets have become more sophisticated, and previously reliable radiographic signs -- such as air trapped in drug packets -- are less likely to be seen, according to Daly.

"Old-style drug packets were loosely wrapped and contained air shadows, but this pattern isn't seen anymore with new wrapping techniques," he said. "Now the packets are coated with wax, latex, fiberglass, or foil to avoid rupture, and typically have less visible internal air. So radiography's sensitivity for identifying drug packets is now considered about 50% at best."

But studies have shown that CT (particularly when used with 3D reconstruction techniques) has high sensitivity for identifying drug packets, ranging between 96% to 100%, and a specificity that ranges from 94% to 100%. In addition, it can visualize trapped air along the rim of the drug packets that x-ray tends to miss, according to Daly.

"Recent developments of liquid cocaine, less radio-opaque packaging, and smaller smuggled volumes of highly concentrated synthetic opiates have made plain x-ray increasingly insensitive for detection of contraband drugs concealed in the body," he said. "CT has high sensitivity for detection of this contraband, especially with use of 3D volume rendering and extended windowing techniques."

Coping with complications

All drug mules and carriers are likely to develop medical complications, Daly said, from acute drug toxicity if packets rupture, to bowel obstruction (even some cases of bowel ischemia and perforation have been reported). Of course, drug users experience medical complications as well, ranging from cardiopulmonary and neurologic conditions to abdominal, musculoskeletal, and dental problems.

Also common is finding concealed contraband incidentally when patients who have experienced assaults or vehicle accidents present in the ER, according to Daly. He described a case of a patient who had hurriedly swallowed a crack pipe to avoid being caught with it, then a week later reported to the ER because of complications from the obstruction the pipe was causing; oblique coronal CT confirmed that the pipe was blocking the distal ileum, and the patient underwent a laparotomy to remove it.

In another case, a survivor of the 1990 Avianca Flight 52 from Bogotá, Colombia, to New York City plane crash on Long Island was being scanned for traumatic injuries and was discovered to be concealing cocaine.

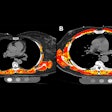

"The patient had suffered traumatic abdominal injuries, and in the course of their CT scan it was noted that they had these foreign bodies in the rectum, which turned out to be cocaine packages," he said.

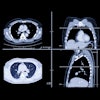

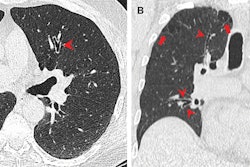

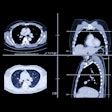

Daly also described a very ill patient who arrived in the emergency room with what appeared to be severe pneumonia on chest radiography.

"The patient had been sick at home taking antibiotics for at least a week," Daly said. "He had a CT scan, which found a horrible pneumonia that had turned into a lung abscess because the patient's bronchus intermedius was obstructed by a vial of crack cocaine. He'd aspirated [rather than swallowing] it when running from police two weeks earlier. This patient had to have the entire lung lobe removed."

Even with these distressing findings on CT in body packing patients, it's important that they understand that they will be treated for these complications without being reported to the police, according to Daly.

"If drugs are identified in a patient, even if the person is a drug pusher, the drugs are removed for the patient's safety and given to the police anonymously to be destroyed," he said. "Hospitals are not part of the police service -- that's not our job -- and ill patients who need urgent care should not be discouraged from coming in because they're worried about being arrested. That's not the way medicine works."