X-ray can help unpack the secrets of the Haitian practice of voodoo, according to a pictorial review published in the Journal of Forensic Radiology and Imaging.

The research demonstrates a trend: Radiography is being used more and more to examine archeological or ethnographical objects without damaging them, according to corresponding author Dr. Philippe Charlier, PhD, of the Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines University in Montigny-Le-Bretonneux, France, and colleagues.

"The use of radiography [gives researchers] a better understanding of contemporary or old objects ... and demonstrates the interest in introducing forensic techniques in ethnology and archeology," the group wrote. "This will allow the 'autopsy' of the artifact with respect for its integrity."

Dr. Philippe Charlier, PhD, from Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines University.

Dr. Philippe Charlier, PhD, from Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines University.Many influences

Haitian voodoo is a mixture of the religious beliefs of various West African peoples, but it also incorporates beliefs from the Taino, a group indigenous to the Caribbean and Florida, as well as Catholicism and European spiritualism. Spells using voodoo dolls can be intended for good or for harm, according to the researchers.

For a spell to work, the doll must incorporate material belonging to the person it is meant to affect, such as hair, nail clippings, or a piece of clothing. A priest, called a "bokor," consecrates the dolls and casts spells. Often, the dolls are part of a larger plot to harm or even murder an intended victim.

Despite the fact that the dolls are illegal in Haiti -- and those caught making them can be punished with prison time -- practitioners continue to use them, Charlier and colleagues found. Charlier collected seven voodoo dolls, called "ouangas," from the Central Cemetery of Port-au-Prince in November 2014.

The researchers used a flat-panel digital radiography (DR) system (Clisis, Primax) to examine the objects: Five were individual dolls made of black or red fabric, while one was a pair of dolls bound together with a white cord -- one doll was made of black fabric and the other was made of white fabric. Both a radiologist and a medical anthropologist read the images taken of the dolls on film and on a workstation (JOFRI, December 2015, Vol. 3:4, pp. 221-225).

Two of the dolls made of black fabric included human hair on the head; one of these also included hair on the genital area, which led Charlier's group to characterize it as male. This doll was found to have a button inserted in its right leg, which was bent and shorter than the left leg.

"[The button] could be used to refine the identification of the target subject," Charlier and colleagues wrote.

Two dolls made of black fabric. All images courtesy of Dr. Philippe Charlier, PhD.

Two dolls made of black fabric. All images courtesy of Dr. Philippe Charlier, PhD.Two of three red cloth dolls appeared to represent men of different sizes, with hair incorporated at the head and the genitals. One of these dolls had a staple in its filling. The third red doll appeared to have been made with features suggesting a woman's hips; the x-ray showed two separate zippers or fragments of the same side of a zipper.

"The presence of the zipper elements inside of the doll could constitute a love charm which joins and holds two things together," the authors wrote.

Three dolls made of red fabric.

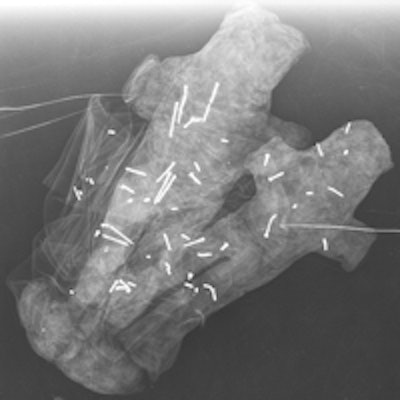

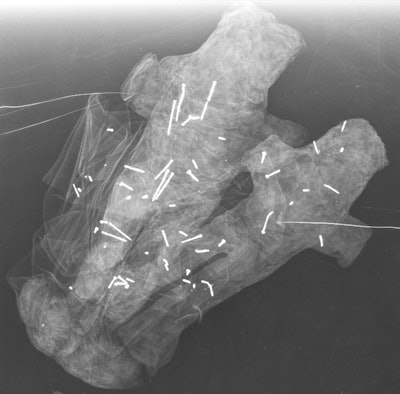

Three dolls made of red fabric.Finally, the paired dolls were not clearly identifiable as male or female, they wrote. The fact that they are a duo could signify a couple, a father and son, or siblings. The researchers found 58 needles in these two dolls: 20 in the white doll, 33 in the black doll, and five scattered across the fabric of each.

Doll pair made of black and white fabric.

Doll pair made of black and white fabric.Cracking the code

Questions remain about the dolls' meaning, according to the team.

"The radiographic analysis raised questions ... about the evil role of each doll and the meaning of the fabric used," the authors wrote. "Were [the dolls] bewitched and not used, or were they made in order to harm and not to kill?"

In any case, imaging offers a safe way to study these Haitian artifacts, Charlier told AuntMinnie.com via email.

"In the past, nobody except the priest himself knew what was inside the dolls," he said. "Radiography allows us to gather information about these objects without destroying them."