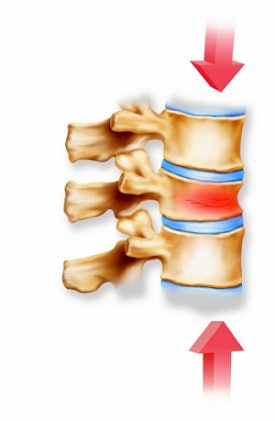

The brief history of vertebroplasty tells a familiar tale, a version of which seems to occur with every procedure developed by interventional radiologists. In this case, interventional radiologists cultivated an innovative, minimally invasive treatment for vertebral compression fractures (VCF).

Word spread to others, including grateful patients and non-imaging specialists such as orthopedic surgeons, thus precipitating the classic turf battle. But unlike most fields where IRs have dared to tread, the turf for treating VCF was a wasteland before radiology stepped in.

Patients often suffered from chronic pain and diminished mobility that wasn’t relieved by the standard treatment of bed rest, bracing and painkillers. Spinal fusion or internal fixation surgery wasn’t an option for older patients with comorbidities and soft bones that were no match for spinal hardware.

Then in 1984, a group led by French radiologist Dr. Hervé Deramond developed percutaneous vertebroplasty -- a therapeutic injection of bone cement into the vertebrae under imaging guidance. The group was seeking a treatment for painful vertebral hemangiomas, myeloma, and metastatic lesions of the spine. Yet the stabilizing effect of injected cement also seemed to relieve the pain caused by more common VCF.

Radiologists at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville performed the first vertebroplasty in the U.S. in 1993. American neurosurgeons and orthopedic spine specialists began embracing the procedure and even performing it themselves. Then in 1996, an enterprising orthopedic surgeon developed a balloon-augmented vertebroplasty, now known as kyphoplasty. Both procedures have rapidly gained in popularity: more than 50,000 kyphoplasties have now been performed, including 17,000 done in the U.S. just last year.

Today, while some radiologists and surgeons do both procedures, many of the former perform only vertebroplasty while most of the latter do only kyphoplasty. It’s a twist on the usual story -- radiologists were first into the arena, and the teams are sharing some equipment -- but there’s still a turf battle going on.

Procedural performance

As far as intracommunity disputes on how to do vertebroplasty, there isn’t much to talk about these days, according to Dr. John Mathis, one of the first radiologists to perform vertebroplasty at UVA and now chairman of radiology at the Virginia College of Osteopathic Medicine in Blacksburg.

"I think the technique is getting fairly similar among physicians," Mathis said. "All physicians vary a little bit in how they do the same procedure, but we’re getting down to where it’s pretty agreed upon what we do and how to keep safe."

|

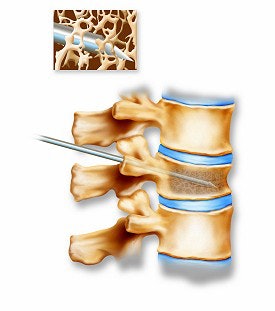

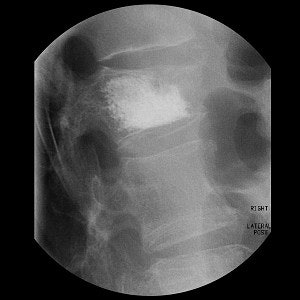

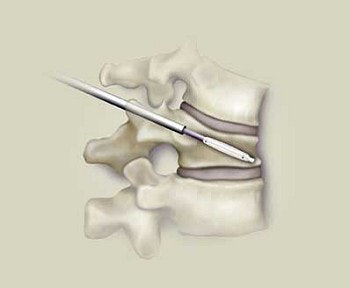

A vertebral compression fracture causing pain and spinal deformity (above). Below, a biopsy needle is guided into the fractured vertebra through a small incision in the skin. Inset shows a magnified view of the interior of the osteoporotic vertebra with the needle in place.

|

That view appears to be borne out by two recent journal articles on how to perform vertebroplasty, one co-authored by Mathis and the second by two other UVA vertebroplasty veterans, Dr. David Kallmes and Dr. Mary Jensen.

While the articles come out a little differently on issues such as mixing antibiotics in the bone cement, and whether to place one or two injection needles, these differences appear to be nonessential. The critical issues, upon which the authors agree, are those that help avoid potential complications from bone cement leakage.

|

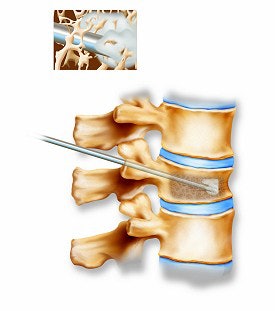

Above, the acrylic bone cement flows into the vertebra, filling the trabecular spaces within the bone. Inset shows a magnified view of the interior of the vertebra with the cement filling in the spaces. Below, the restored vertebra with the hardened cement, stabilizing the vertebral structure and relieving pain. Inset shows magnified view of the interior of the restored vertebra.

|

To that end, both articles advise the use of fluoroscopic guidance, with biplane monitoring if available. While CT’s superior contrast resolution was briefly a draw for some practitioners, "CT does not afford one the opportunities to watch the cement as it is being injected or to alter the injection volume in real time if a leak occurs," wrote Mathis and Dr. Wayne Wong (Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, August 2003, Vol.14:8, pp.953-960).

"Perhaps the most critical attribute that facilitates safe vertebroplasty is excellent opacification of cement," noted Kallmes and Jensen. Both articles recommend adding barium sulfate to polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) bone cement to achieve sufficient opacification (Radiology, October 2003, Vol.229:1, pp.27-36)

Safety debate

The complications that have occurred with vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty -- including two deaths -- prompted an alert by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) in October 2002.

|

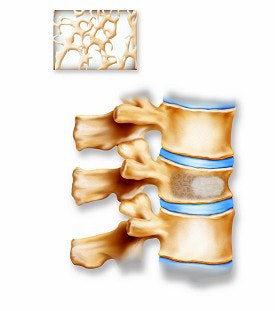

| Final result of a vertebroplasty procedure on a lateral radiograph. Image courtesy of Dr. John Mathis. |

The alert cited complications related specifically to the leakage of bone cements, including soft tissue damage and nerve root pain and compression. The CDRH also cited pulmonary embolism, respiratory and cardiac failure, abdominal intrusions/ileus as other complications generally associated with the use of bone cements in the spine; Mathis and Wong noted that the deaths appeared to result from pulmonary compromise due to fat or cement emboli.

The FDA alert appears to have had little, if any, impact on procedural volume: Mathis said he hasn’t received an queries from patients about it. In terms of the orthopedists-versus-interventionalists turf war, the CDRH alert applied equally to the competing procedures.

|

Top, radiography of a compression fracture. Center, vertebroplasty needle insertion. Below, post-procedure. Images courtesy of Dr. Martin Radvany.

|

"Each of these types of complications has been reported in conjunction with use of bone cements in both vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty procedures," the CDRH wrote. "Current information is insufficient to establish overall complication rates for either of these procedures or to distinguish the types and incidence of complications associated with the use of bone cements in each type of procedure."

Notwithstanding the opinion, kyphoplasty partisans still think their procedure is better. David Schummers, director of investor relations for Sunnyvale, CA-based Kyphon -- the sole manufacturer of kyphoplasty kits -- said that kyphoplasty has a 1% complication rate versus a 7% rate for vertebroplasty.

In contrast, the Vertebroplasty.com Web site, developed by cement-delivery-devicemaker Parallax Medical of Scotts Valley, CA, tells potential patients that complications from the procedure are "rare, affecting only about 1-3% of patients with osteoporotic compression fractures."

Comparing procedures

The claims that kyphoplasty is safer are disputed by Mathis, who helped test the Kyphon balloon at Johns Hopkins and was the first radiologist to use it in clinical practice.

"Even though I’m a stockholder in Kyphon, I have to be honest in my opinion," he said. "Most of the things that you hear are differentially positive about kyphoplasty right now are actually marketing hype, and are not as of yet substantiated by scientific data."

"Both (procedures) have excellent safety in the hands of good physicians, both of them relieve pain similarly," Mathis said. "And if kyphoplasty really restored the vertebral-body height, it would arguably be worth more."

|

| Through two small incisions, two KyphX balloons are inserted into narrow pathways into the fractured bone. |

Height restoration has been a major selling point for balloon-augmented vertebroplasty, as surgeons have sought to address kyphosis or spine curvature as well as pain. Kyphoplasty results compiled by spinal surgeon Dr. Isador Lieberman and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio found that some patients had as much as 3 cm in vertebral height restored (Clinical Orthopedics, October 2003, 415 supplement, pp. S176-186).

But Mathis said that that Lieberman’s mean restoration rate of 3 mm was less than impressive. "So you’re paying a huge amount of additional money to potentially restore height, but you’re not getting that most of the time," Mathis said. "Therefore, I’ve moved away from kyphoplasty on the average patient."

|

| The balloons are inflated, moving the collapsed portion of the vertebra. The purpose is to restore the fractured bone to its original shape. |

Part of the problem, Mathis explained, is that Medicare administrators often won’t pay for kyphoplasty (or vertebroplasty) until the patient has spent at least 30 days on the standard medical regime of bed rest and painkillers. Bone will generally begin to "heal" or rigidify with three weeks, making it more difficult to move the vetebra as time passes.

Lieberman agreed that some patients won’t gain much from kyphoplasty, which is why he takes issue with Mathis’ interpretation of his results. "He’s quoting my very first paper where we measured all comers and we didn’t stratify for the different fracture configurations," Lieberman said. "If we pick the right fracture configuration and we get to the vertebral body in time, we get very, very good height restoration."

Moreover, Lieberman said, Mathis is exhibiting "tunnel vision" by focusing on height restoration as the only justification for kyphoplasty. In Lieberman’s estimation, the procedure:

- is safer than vertebroplasty because cement is injected in a controlled fashion into a cavity

- reduces the rate of subsequent remote and adjacent-level fractures compared to natural occurence while vertebroplasty increases the subsequent fracture rate

- has better clinical outcomes -- a position bolstered mainly by the fact that no one else appears to be tracking and reporting data as zealously as Lieberman himself.

Cement leakage does occur more often in vertebroplasty, in a reported 20-70% of cases, compared with the extravasation reported in fewer than 10% of kyphoplasties. But the highest reported rate comes from the oldest reported series, and the only demonstrated effect of non-critical epidural leakage is a temporary attenuation of vertebroplasty’s therapeutic benefits (Journal of Neurosurgery, January 2002, Vol. 96:1 supplement, pp.56-61).

In any case, neither Mathis nor Lieberman said they anticipate a head-to-head trial of vertebroplasty versus kyphoplasty that would resolve the leakage debate or any other claims. Both cited alleged reluctance on the part of the other camp’s partisans to undertake such research.

Financial issues

While both vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty are being reimbursed by Medicare in all 50 states, kyphoplasty is indisputably more expensive, for several reasons.

Kyphoplasty is typically performed in hospital surgical suites under anesthesia, while vertebroplasty is generally an outpatient procedure. Kyphoplasty takes about 15 minutes longer than vertebroplasty, according to Mathis. And the kit including cement for vertebroplasty costs about $400, again according to Mathis, while a kit for kyphoplasty including cement costs close to $4,000.

Kyphon encourages use of its kits only in operating rooms, and requires that any interventional neuroradiologist who performs kyphoplasty have surgical backup available. Hospital costs are generally billed under the Medicare DRGs 234 and 233, which pay from $5,000 up to $10,000, according to company spokesman Schummers.

|

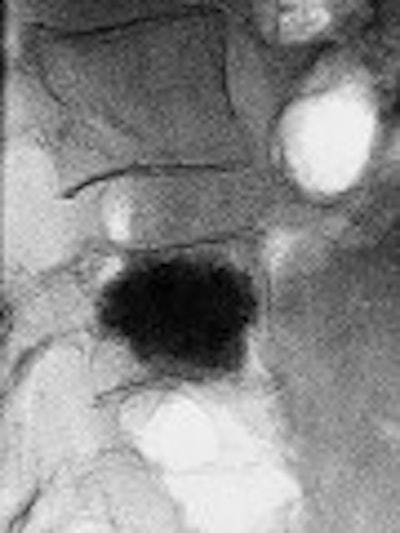

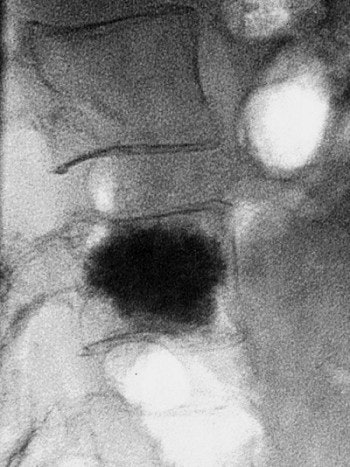

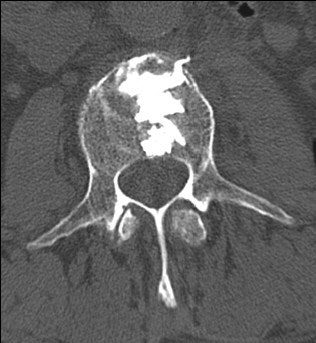

Eighty-year-old man with renal cell carcinoma who presented with lower back pain. Control CT scan (below) acquired immediately after vetebroplasty shows homogenous cement distribution in tumor necrosis with small ventral leakage. Control radiography (above) acquired three months after procedure shows stable vertebral body with unchanged location of cement filling. Schaefer O, Lohrmann C, Markmiller M, Uhrmeister P, Langer M, "Combined Treatment of a Spinal Metastasis with Radiofrequency Ablation and Vertebroplasty," (AJR 2003, Vol.180, pp.1075-1077).

|

While there is no nationwide CPT code for the professional performing kyphoplasty, the procedure is being reimbursed in every state either under state-specific codes or on a case-by-case basis. The professional reimbursement runs from a low of $500 to a high of $1,400 per procedure, Schummers said.

Mathis maintained that the relatively low reimbursement will diminish physician interest in kyphoplasty. "Surgeons aren’t going to spend their time doing these if they don’t get a whole lot more money than that," he said. "And frankly I think it pays about what it’s worth."

While Lieberman agreed that even salaried surgeons like himself will complain about poor financial recognition of their work, he maintained that kyphoplasty is here to stay.

"My institution does well by the kyphoplasties because we’ve learned to play within Medicare’s rules. We are able to do this in a cost-effective fashion." And, "the patient results are such that we’re not going to stop doing this," he said.

Future developments

Demand for fracture treatment is likely to increase for the next 10 years, Lieberman said, as the population ages without the benefit of strategies to prevent osteoporosis that will emerge in a decade or two. Both procedures are currently attracting more patients from self-referral and initiatives such as the marketing tool kit offered to vertebroplasty practitioners by Parallax Medical.

| For the latest news in vertebroplasty, check out the following presentations at the 2003 RSNA: |

|

|

|

| Education Exhibits | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Refresher Courses | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Scientific Papers | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Scientific Posters | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| For more information, visit www.rsna.org |

And over time, a greater consensus is likely to emerge among physicians as to which patients will benefit from which procedure.

"We’re going to be using all of these different modalities, in what proportion I’m not sure yet," said Lieberman. "My bias is that the vast majority of patients will do better with a kyphoplasty-type procedure."

"However," he added, "as we enter into the future of the treatment of spinal pathologies, a vertebroplasty approach may be the better approach to administer a biologic substance as opposed to an inert biomechanical substance. If I can inject bone cells in there to give those osteoporotic patients or tumor patients real bone, then we’ve got a major advance."

By Tracie L. ThompsonAuntMinnie.com staff writer

November 18, 2003

Related Reading

Book review: Percutaneous Vertebroplasty, September 30, 2003

UK issues alert over spinal fracture cements, July 31, 2003

Osteoporosis underdiagnosed in patients with vertebral compression fractures, April 24, 2003

FDA urges caution with off-label use of bone cement in vertebroplasty, April l7, 2003

New vertebral fractures often occur following percutaneous vertebroplasty, February 25, 2003

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com