A minimally invasive procedure called cryoablation that uses ice to freeze and destroy tumors has proven effective for women with large breast cancer tumors, according to a study presented March 27 at the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) meeting in Salt Lake City.

The finding suggests the technique may provide a new treatment path for women who are not candidates for lumpectomy, or surgical removal, noted Yolanda Bryce, MD, an interventional radiologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, and senior author of the study.

“Surgery is still the best option for tumor removal, but there are thousands of women who, for various reasons, cannot have surgery,” Bryce said, in a news release from SIR. “We are optimistic that this can give more women hope on their treatment journeys.”

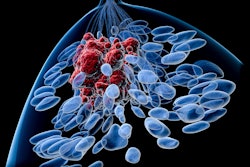

Cryoablation uses imaging guidance typically with ultrasound or CT to locate tumors. An interventional radiologist then inserts small, needle-like probes into the breast to create an ice ball that surrounds the tumor and kills the cancer cells.

Previous research suggests that when the procedure is combined with hormonal therapy and radiation, patients can have nearly 100% of their tumors destroyed, Bryce noted. To date, however, the treatment has been successfully used only to treat tumors smaller than 1.5 cm.

The research was presented during the meeting's closing plenary session by Jolie Jean, MD, a radiology resident at Weill Cornell Medicine. The study evaluated the technique in 60 patients with primary breast cancer tumors larger than 1.4 cm who were poor surgical candidates or who refused surgery. Patients underwent cryoablation between January 2017 and March 2023. Out of the 60 treated patients, 48 had invasive ductal carcinoma, five patients had invasive lobular carcinoma, and seven patients had other histology. Tumor size ranged from 0.3 cm to 9 cm, with average size of 2.5 cm.

The treatment consisted of a freeze-thaw cycle ranging between 18 to 28 minutes, followed by active thaw to remove the probes, which was performed with minimal or no sedation, depending on the eligibility and preference of the patient. Patients were able to go home on the same day once the treatment was complete.

Follow-up imaging was performed after the procedure by mammogram, ultrasound, or in some cases contrast-enhanced mammogram or MRI, based on patient eligibility and preference.

After a median follow-up of 16 months, there was a recurrence rate of 10% (six patients), according to the findings. In addition, the researchers found that patients with poorly differentiated disease had a higher risk of recurrence. Tumor size did not differ between the recurrence and nonrecurrence groups.

“With the use of treatment techniques as described, cryoablation can be performed effectively in patients with varying tumors,” Jean noted.

Ultimately, when treated with only radiation and hormonal therapy, tumors will eventually return, so the fact that the group saw only a 10% recurrence rate in the study is promising, Bryce added.

The group plans to continue to follow the patients to collect data on the long-term effectiveness of cryoablation and to better understand the impact that combined adjuvant (e.g., hormone therapy and radiation) therapies can have on this patient population.