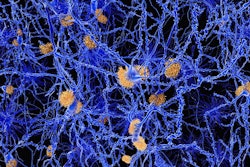

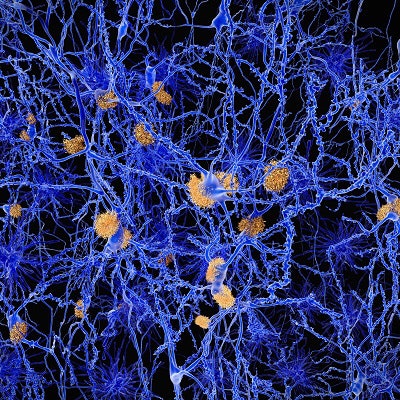

If physician-assisted death were legal, how many people with elevated beta-amyloid levels would opt for it if they experienced a cognitive decline due to Alzheimer's disease? Not that many, according to a research letter published online April 29 in JAMA Neurology.

In a survey of patients with high beta-amyloid levels, only approximately 20% of study participants said they would consider physician-assisted death if they became cognitively impaired, were suffering, or were a burden to others. In comparison, a majority of the subjects cited "personal, religious, or philosophical objections" as reasons why physician-assisted death wouldn't be right for them.

"Our findings suggest that learning one's amyloid imaging result does not change baseline attitudes regarding the acceptability of physician-assisted death," wrote the researchers led by Emily Largent, PhD, from the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia. "However, among those who indicate a personal openness to physician-assisted death, an elevated amyloid imaging result and the associated risk of cognitive decline are viewed as relevant to physician-assisted death-related decision-making."

Currently, seven U.S. states allow for competent, terminally ill patients to choose a physician-assisted death, but that choice is prohibited for people with dementia. But what if that right was extended to those with Alzheimer's disease? Would patients take that path, if they thought their condition could or would become progressively worse?

To find that answer, the researchers recruited 50 participants from the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer's (A4) study, which is designed to determine the efficacy of Eli Lilly's investigational drug solanezumab for slowing cognitive decline in persons with amyloid accumulation. They also included 30 people from the Longitudinal Evaluation of Amyloid Risk and Neurodegeneration (LEARN) study, which includes subjects with no such amyloid deposition.

Within the A4 cohort were 35 people (70%) between the ages of 65 and 74 and 15 people (30%) 75 years and older. The LEARN group included 25 people (83%) between 65 and 74 years old and five people (17%) 75 years and older. All 80 subjects were interviewed four to 12 weeks after learning their amyloid levels, and 77 also received a follow-up interview at 12 months. The later interviews included a question about physician-assisted death after some participants "spontaneously mentioned" it during their earlier interviews, the authors noted.

When asked if they would contemplate physician-assisted death, approximately two-thirds of the people with elevated amyloid levels said they "neither had nor would" consider that action. They cited "personal, religious, or philosophical objections that led them to conclude physician-assisted death would not be right for them," Largent and colleagues noted. Interestingly, these subjects expressed higher feelings of optimism or hope about the future than the approximately one in five interviewees who said they would consider physician-assisted death in the event of cognitive impairment, suffering, or becoming a burden to others.

Those who would consider physician-assisted death were relatively more likely to report preparing for the future via legal or financial planning than those who would not consider physician-assisted death. The researchers also noted that some individuals with elevated beta-amyloid levels were ambivalent about physician-assisted death. Many of these subjects described efforts to learn more about it, according to the authors.

"Understanding attitudes toward physician-assisted death held by individuals at risk for cognitive decline owing to Alzheimer's disease is important to inform ongoing debates about the scope of access to physician-assisted death," the researchers concluded. "Further research is indicated to better understand end-of-life care preferences among people at increased risk for dementia."