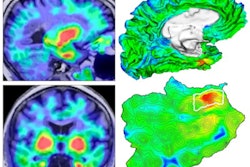

PET scans of older Americans have revealed a potential link between the quality of air they breathe and the presence of brain plaque linked to Alzheimer's disease, according to a study published online November 30 in JAMA Neurology.

The revelations come from more than 18,000 participants in the Imaging Dementia-Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) study who were exposed to extensive air pollution from a variety of sources. PET scans showed that these individuals were 10%-15% more likely to develop amyloid plaques compared with individuals from the least-polluted areas.

"This study provides additional evidence to a growing and convergent literature, ranging from animal models to epidemiological studies, that suggests air pollution is a significant risk factor for Alzheimer's disease and dementia," said senior author Dr. Gil Rabinovici from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Memory and Aging Center and UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

Previous studies have suggested that air pollution is associated with dementia and Parkinson's disease, can adversely affect cognition, and can slow behavioral and psychomotor development in children. To further advance current data and zero in on a possible connection between poor air quality and mild cognitive impairment, Rabinovici and colleagues targeted the presence of amyloid plaques, which are a biomarker of the condition and often a prelude to Alzheimer's.

The researchers analyzed amyloid-PET scans from 18,178 older adults (mean age, 75.8 ± 6.3 years), 10,991 (61%) of whom were diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment and 7,187 (39%) of whom had dementia. Their degree of exposure to air pollution was based on predicted fine particulate matter (PM2.5), which calculates the amount of particles that contribute to pollution, and ground-level ozone concentrations.

Air quality data was estimated for the years 2002 to 2003, approximately 14 years prior to the amyloid-PET scans and again from 2015 to 2016 approximately one year before amyloid-PET imaging with one of three tracers: florbetapir (Amyvid, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals), florbetaben (Neuraceq, Life Molecular Imaging), or flutemetamol (Vizamyl, GE Healthcare).

The key measure is determining an association between air pollution and the likelihood of a positive amyloid-PET scan was an odds ratio (OR), which was adjusted for a participant's demographic, lifestyle, and socioeconomic data, as well as medical comorbidities that included respiratory, cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, psychiatric, and neurological conditions.

The researchers found that seniors living in areas with higher estimated PM2.5 concentrations in 2002 to 2003 -- in other words, the worst air quality -- were 10% more likely to have amyloid plaques appear on their PET scans (adjusted OR, 1.10). The chances increased to 15% (OR, 1.15) when 2015-2016 poor air quality data was compared with amyloid-PET results. The association between air pollution and amyloid plaque was statistically significant (p = 0.003) after adjusting for demographic, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors as well as medical comorbidities, the authors added.

Given the results, Rabinovici and colleagues suggested "the need to consider airborne toxic pollutants associated with amyloid-beta pathology in public health policy decisions and to inform individual lifetime risk of developing Alzheimer's disease and dementia."