In one of the only large-scale studies on the issue, researchers have shown that surveillance imaging in patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) saves lives, according to a study published online January 10 in Radiology.

In an analysis of statewide cancer registry data, researchers at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City found lower mortality rates in patients with head and neck cancer who underwent imaging with PET/CT and CT and/or MRI up to two years after treatment. The findings support extending surveillance imaging beyond current recommendations, they wrote.

"No surveillance imaging recommendation beyond six months is included in the current National Cancer Consortium Network HNC guidelines because of the lack of high-level evidence," wrote lead author Dr. Yoshimi Anzai, PhD, and colleagues.

The prognosis for patients with locally advanced HNC is poor, with approximately 40% of patients experiencing recurrence. Surveillance imaging is performed to detect recurrence of disease before clinical symptoms and signs develop. Yet there is lack of high-level evidence to support its use to improve overall patient mortality rates, the authors wrote.

To elucidate the issue, the researchers identified 1,004 patients who underwent PET/CT, CT, and/or MRI for HNC between January 2012 and December 2017. The group included 902 patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) HNC and 102 patients with non-SCC. Approximately 74% (666 of 902) of patients with SCC and 74% (75 of 102) of patients with non-SCC underwent surveillance imaging at least once.

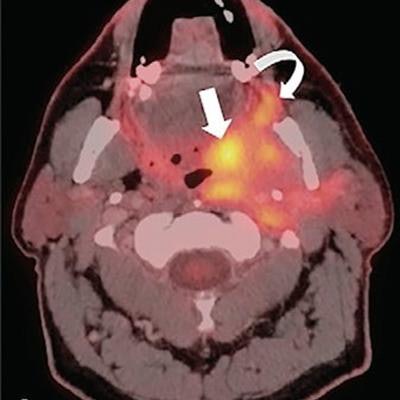

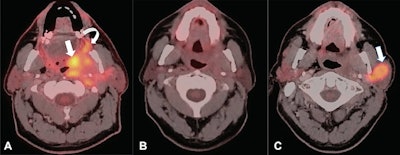

A 62-year-old man with a history of human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. (A) Axial fused image of FDG-PET and contrast-enhanced CT shows a large infiltrative tumor centered in the left palatine tonsil (straight arrow) extending to the left soft palate, retromolar trigone (curved arrow), medial pterygoid muscle, and left parotid gland. The patient underwent chemotherapy and radiation therapy. (B) Axial fused image of FDG-PET and contrast-enhanced CT performed 4 months after chemotherapy and radiation therapy shows marked reduction of metabolic activity. Mild residual soft-tissue fullness is present in the left parapharyngeal space, presumably representing posttreatment changes. (C) The patient underwent surveillance FDG-PET/CT, which shows a recurrent mass in the left parotid gland (arrow) with avid FDG uptake (maximum standardized uptake value, 24.5). The patient remained asymptomatic. The biopsy of the left parotid mass showed recurrent squamous cell carcinoma. Image and caption courtesy of Radiology.

A 62-year-old man with a history of human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. (A) Axial fused image of FDG-PET and contrast-enhanced CT shows a large infiltrative tumor centered in the left palatine tonsil (straight arrow) extending to the left soft palate, retromolar trigone (curved arrow), medial pterygoid muscle, and left parotid gland. The patient underwent chemotherapy and radiation therapy. (B) Axial fused image of FDG-PET and contrast-enhanced CT performed 4 months after chemotherapy and radiation therapy shows marked reduction of metabolic activity. Mild residual soft-tissue fullness is present in the left parapharyngeal space, presumably representing posttreatment changes. (C) The patient underwent surveillance FDG-PET/CT, which shows a recurrent mass in the left parotid gland (arrow) with avid FDG uptake (maximum standardized uptake value, 24.5). The patient remained asymptomatic. The biopsy of the left parotid mass showed recurrent squamous cell carcinoma. Image and caption courtesy of Radiology.According to the findings, a lower mortality rate was associated with SCC in patients who underwent surveillance imaging for regionalized cancer stage (hazard ratio [HR], 0.55; p = 0.005) and distant cancer stage (HR, 0.40; p = 0.01) compared with those without surveillance imaging. The median years of survival was 3.76 years for the surveillance imaging group and 2.89 years for the no-surveillance imaging group in patients with SCC.

"The surveillance imaging protective association was observed up to two years after treatment completion," Anzai and colleagues wrote.

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Barton Branstetter of the University of Pittsburgh wrote that the findings support the current consensus of most head and neck radiologists and should be seen as a launching point for further studies.

Questions that need to be answered, for instance, include whether clinicians should use PET/CT as the first post-treatment examination, and then switch to CT every three to six months, or whether PET/CT should be used at every examination so that surveillance can be concluded sooner, he wrote.

"Anzai et al have shown that radiologic surveillance saves lives -- now we need to perfect our imaging strategies," Branstetter wrote.