PET brain scans of former NFL players with dementia due to repetitive head impacts do not show typical signs of Alzheimer’s disease, according to a study published October 5 in Alzheimer's Research and Therapy.

The study has implications in how former players with dementia are treated and potentially compensated in the NFL’s ongoing controversial “concussion settlement,” noted first authors Robert Stern, PhD, and doctoral student Diana Trujillo-Rodriguez, of Boston University, and colleagues.

“This class action settlement provides substantially higher monetary compensation to former players with a diagnosis of [Alzheimer's disease] than for players with similar cognitive impairment and dementia but without an [Alzheimer's disease] diagnosis,” the group wrote.

Moreover, a potential yet difficult diagnosis in many of these cases may be a unique disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), according to the authors. CTE is a neurodegenerative disease caused by repetitive head impacts, but can only be definitively diagnosed in patients after their death, the researchers noted.

Thus, the aim of the study was to explore whether amyloid PET scans could rule out Alzheimer’s disease in these cases and identify a potential gap in care for patients with potential CTE.

The investigators examined 237 men between the ages of 45 and 74, including 119 former professional and 60 former college players, with and without cognitive impairment and dementia. They compared results in 58 men of the same age without a history of contact sports or traumatic brain injuries.

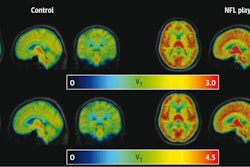

The team used PET scans with a beta-amyloid protein radiotracer called florbetapir. This tracer binds to the plaque and reveals it on imaging, with standard uptake value ratios (SUVRs) of the tracer serving to quantify accumulated levels, where present.

According to the findings, there were no diagnostic group differences either in florbetapir average SUVR or the proportion of elevated florbetapir uptake, the researchers wrote. Average SUVR means also did not differ between exposure groups, and florbetapir uptake was not significantly associated with years of football exposure, cognition, or daily functioning.

“We found that most former professional and college football players, ages 45-74 years, with and without cognitive impairment or dementia, did not have in vivo amyloid PET evidence of [Alzheimer’s disease],” the group wrote.

The impact on compensation for former players with brain injuries and dementia could be significant, the authors wrote.

For example, a 62-year-old former player who receives a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease by a “settlement-qualified neurologist” without an amyloid PET scan would be eligible for compensation of $950,000, they noted. Conversely, if the same patient has an amyloid PET scan as part of their evaluation and the results are negative, the player would be eligible for compensation of only $290,000, they added.

Ultimately, additional studies are needed to clarify the extent to which cognitive impairment in former football players with a history of repetitive head impacts is related to other neuropathological changes, including CTE, the authors wrote.

Until sensitive and specific biomarkers for CTE are available, a clinical “diagnosis by exclusion” using amyloid PET scans for Alzheimer’s disease may be appropriate, they wrote.

“The compensation criteria for the NFL settlement may need to be modified based on new medical/scientific findings, including findings that cognitive impairment and dementia in many former NFL players may be caused by non-Alzheimer's disease neuropathology,” the group concluded.

The full article can be found here.