A PET study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has called into question the theory that ultraprocessed foods elicit brain responses akin to addictive drugs.

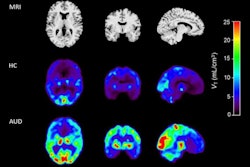

A group at the NIH’s Center on Compulsive Behaviors measured striatal dopamine responses on PET scans before and after healthy adults consumed ultraprocessed vanilla milkshakes. They found no significant difference in dopamine responses, nor were individual responses significantly related to fat mass.

“Our results do not imply that ultraprocessed foods high in fat and sugar are not addictive but rather call into question the mechanism by which this may occur,” noted lead author Valerie Darcey, PhD, and colleagues. The research was published March 4 in Cell Metabolism.

Ultraprocessed foods have been theorized to be addictive due to their consumption eliciting an outsized dopamine response in brain reward regions similar to drugs of abuse, the authors explained. They noted that the theory is based on a seminal study published in 2001 in the Lancet but that more recent research suggests a different mechanism.

To explore the issue further, the group enrolled 50 young, healthy adults over a wide body mass index (BMI) range (20 to 45 kg/m2). Participants completed a five-day inpatient stay during which their diets were stabilized. For the experiment, they underwent two carbon-11 raclopride PET scans (raclopride binds to D2-dopamine receptors), one before and then one 30 minutes after consuming a vanilla milkshake. Participants fasted for 12 hours before the first scan.

According to the analysis, interindividual responses were highly variable, yet mean dopamine signaling and activity among the group was not significantly different between the scans. Moreover, neither kilograms of fat mass, body fat percentage, age, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, nor insulin sensitivity were significantly correlated with dopamine responses.

“We believe the most likely interpretation of our data is that consuming ultra-processed milkshakes high in fat and sugar produces small but highly variable changes in postingestive striatal dopamine that were unrelated to adiposity,” the group wrote.

Instead, the group suggested that dopamine responses may be related to perceived hunger levels. They noted that changes in hunger levels before and after the milkshake correlated with whole striatal dopamine responses, such that the more hunger was suppressed by the milkshake, the greater the degree of observed dopamine release.

Ultimately, the findings call for further research, the group wrote.

“Future studies should investigate additional features of dopamine signaling (e.g., synthesis and clearance) as potential mechanisms by which ultra-processed foods high in fat and sugar may promote overconsumption,” the researchers concluded.

The full study is available here.