Adaptive stress coping is associated with cognitive resilience in unimpaired older adults at-risk for Alzheimer’s disease, researchers have reported.

The finding is from an analysis of patients in whom more frequent use of adaptive coping was associated with better cognitive trajectories, independent of amyloid and tau brain pathology on PET imaging, noted Eleni Palpatzis, PhD, of Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, and colleagues.

“These findings suggest that enhancing adaptive coping strategies represents a potentially modifiable target for interventions aimed at delaying cognitive decline in individuals with preclinical [Alzheimer’s disease],” the group wrote. The study was published November 16 in Alzheimer’s and Dementia.

While previous research has linked stress, coping, and related psychological factors to Alzheimer’s disease brain pathology and cognitive decline, few studies have assessed whether coping modifies the relationship between pathology and cognitive trajectories, the researchers explained.

To bridge the gap, in this study, the group included 99 cognitively unimpaired older adults (mean age, 75; 59% females) from two previous Alzheimer’s disease studies who completed coping strategy assessments during the COVID-19 pandemic. This allowed the researchers to examine responses to a common stressor that increased psychiatric symptoms, since the pandemic was a traumatic event, they noted.

The first questionnaire was completed by participants between May 7 and May 26, 2020, about two months after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S., and the second was between March 23 and May 13, 2021. The questionnaires were designed to assess eight adaptive strategies (active coping, planning, positive reframing, humor, emotional support, instrumental support, acceptance, and religion) and six maladaptive strategies (self-distraction, denial, substance use, behavioral disengagement, venting, and self-blame).

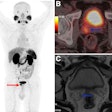

Meanwhile, participants had also undergone yearly longitudinal cognitive assessments over 5.3 years on average and cross-sectional PET imaging with the Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) to assess beta-amyloid pathology and with F-18 flortaucipir PET to assess tau pathology.

According to the analysis, more frequent use of adaptive coping was associated with better cognitive trajectories, even after accounting for beta-amyloid and tau pathology. Further, three-way interactions between tau, adaptive coping, and time indicated that individuals with elevated tau and less adaptive coping showed accelerated cognitive decline, the researchers reported.

Moreover, although tau was found to moderate the rate of decline, the protective benefit of more frequent coping persisted despite pathology levels, so that high copers with elevated tau showed significantly slower decline than low copers with similar tau levels, according to the findings.

“Our findings provide first evidence that adaptive coping strategies may serve as cognitive resilience factors in preclinical [Alzheimer’s disease],” the group wrote.

The researchers offered several biological mechanisms that may explain the protective effect. First, the mechanisms underlying the relationship may involve reduced stress activation, as stress has been linked to hippocampal atrophy, dysregulated hypothalamic pituitary adrenal-axis function, and accelerated cognitive aging, they suggested.

Second, individuals employing more adaptive coping strategies may benefit from “brain maintenance,” which may allow them to tolerate higher levels of pathology before showing cognitive decline, they added.

Given the potentially modifiable nature of coping strategies, coping-focused interventions may offer a practical and accessible approach to cognitive preservation, the researchers wrote.

“Future research should explore the neurobiological mechanisms underlying these resilience effects and examine the effectiveness of targeted interventions to enhance adaptive coping in vulnerable populations,” they concluded.

The full study is available here.