TORONTO - A common thread linked a string of lymphoma studies presented Tuesday at the Society of Nuclear Medicine meeting. That is, as the value of FDG-PET imaging in recurrent lymphoma staging was reaffirmed, the scans were also found to be far more prognostic after the first few rounds of chemotherapy than later in treatment.

Significant diminution of FDG uptake in early chemotherapy has a high prognostic value, and represents a crucial point at which alternative treatment methods can be used to avoid unnecessary toxicity in patients who will not respond to further chemotherapy, presenters and attendees said.

The first presentation, by Dr. Jean-Emmanuel Filmont from the University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine, affirmed the value of PET in the staging of lymphoma. The study sought to assess PET's impact in staging lymphoma patients as compared to conventional imaging methods, mostly CT, in patients with residual or recurrent disease.

The study population consisted of 95 patients with a mean age of 53 years, 18 of whom had Hodgkins Lymphoma (HL), and 77 who had non-Hodgkins disease. Thirty-one patients had high-grade lymphoma, 19 intermediate grade, and 15 of unknown grade, Filmont said. The clinical stage was determined according to the Ann Arbor classification, which was verified by the outcome in at least 68 patients.

All patients had been treated with chemotherapy, radiation or stem-cell transplantation at a median interval of 22 weeks before PET imaging. Staging with conventional imaging was performed up to three months before PET imaging (an extended period which Filmont acknowledged as a study limitation).

Each patient underwent an average of 3.2 conventional imaging studies in the course of staging. A variety of exams were used including plain films of the neck, chest and abdomen, ultrasound, and bone scintigraphy. However CT was the most commonly used modality, and most CT scans were performed within 3 months of PET imaging, Filmont said. FDG-PET scans were performed on an Ecat Exact HR or HR+ scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Iselin, NJ).

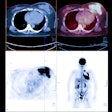

Compared to conventional imaging methods, PET downstaged 27% of patients, upstaged 10 patients (9.5%), and had no impact on the staging of 58 patients (61%). Of 14 patients with negative PET, 12 remained disease-free at follow-up. There were two false-positive PET results. One consisted of a lung infection which was resolved by antibiotic therapy, and the second false-negative result involved the mediastinum, he said. Overall, PET changed the clinical stage of 46% of the patients.

The sensitivity of conventional imaging was 82.9% as compared to 90.2% for PET. Results were statistically significant in specificity, which was 46.7% for conventional imaging, compared to 93.3% for PET. The positive predictive value (PPV) of conventional imaging was 68% compared with 93.3% for PET, and the negative predictive value (NPV) was 67% for conventional imaging. Of 14 patients with negative PET results, 12 remained disease-free at follow-up, Filmont said.

While PET was more successful as a negative predictor of disease-free survival, it was useful for all lymphoma staging, he said, and superior to conventional imaging. Moreover, PET did the job in one imaging exam as opposed to more than 3 exams for conventional imaging, he concluded.

Predictor of disease-free survival?

A second presentation by Dr. Lela Kostakoglu from New York Presbyterian Hospital and Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York City found that FDG-PET successfully predicted outcomes after the first cycle of chemotherapy in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkins (NHL) and Hodgkins lymphoma (HL), yet had much lower prognostic value at the end of therapy.

Kostakoglu and colleagues studied 30 patients, 17 NHL and 13 with HL, with a mean age of 52.3 years. The researchers sought to assess the value of PET during early chemotherapy as a predictor of durable disease-free survival.

FDG-PET imaging was performed on all 30 patients before and within 2 weeks after a single cycle of chemotherapy, using and MDC-AC scanner (Adac Laboratories, Milpitas, CA), attenuation correction, and a dose of 5 mCI of 18 FDG. Twenty-three patients had follow-up imaging between six months and two years (median, 18 months) after initial-round chemotherapy. Subsequently, one-year disease-free survival was compared between patients with positive and negative FDG-PET obtained after the first cycle of chemotherapy.

At follow-up there was a statistically significant difference in failure-free survival between patients with positive and negative PET results, Kostakoglu said. Ten patients with positive PET had disease progression or recurrent disease, as compared to 3 patients with negative PET. Similarly, only 2 patients with negative PET, and 12 with positive PET results, remained disease-free at follow-up.

Thus, the sensitivity of PET was 82% after first-cycle therapy, and only 45% after completion of therapy. PET's specificity was 92% for both time periods. Disease sites for the two false-positive results were both in the mediastinum. All of the false negative cases had a brief clinical response. However, there was eventually a recurrence of disease at the original site.

In progression-free survival time, the researchers found a dramatic difference between the two groups of patients: 16 months vs. 6 months in patients with negative PET after the first round of chemotherapy, Kostakoglu said.

"In conclusion we can say that .. after the first cycle of chemotherapy FDG-PET predicts disease-free survival with high sensitivity and specificity," she said. "FDG-PET has a greater sensitivity, positive predictive value and accuracy after the first cycle of chemotherapy than .. after additional therapy for both non-Hodgkins lymphoma and Hodgkins disease."

Asked for a possible explanation, Kostakoglu said that chemotherapy eventually takes a toll on all tumor metabolism. However, in resistant tumor that does not respond to the first rounds of chemotherapy, the diminished metabolic activity and reduced uptake seen in later therapy may be only temporary.

Preventing toxicity

Finally, a study by Dr. Tatsuo Torizuka from Hamamatsu Medical Center in Japan looked at 17 patients with pathologically proven lymphoma, including 14 with NHL and 3 with HL who underwent PET imaging at baseline, and again following 2-3 weeks of chemotherapy.

Clinical observations were obtained for the following 6 months in all patients. Ten of the 17 patients achieved disease-free remission after completion of therapy, while 7 patients did not respond to therapy. Baseline SUV did not correlate with the therapeutic response, Torizuka said, but the 10 responders showed a significantly greater reduction of SUVs after 2 cycles of chemotherapy, as compared with the 7 non-responders (mean, 70.9% vs. 23.9%).

After two cycles of chemotherapy, there was no significant difference in SUV between the responders and the non-responders. Torizuka concluded that the early response could help physicians avoid additional chemotherapy and toxicity in non-responders, since it does not appear to produce additional benefits.

An audience member commented that knowledge of FDG-PET's predictive value early on in therapy represented an important opportunity to evaluate alternative treatments in patients before receiving additional chemotherapy, which can result in additional toxicity without added curative effects in many patients.

Other presentations confirmed PET's apparent prognostic value following early treatment for lymphoma as compared to later treatment cycles. However, reimbursement problems could impede further exploration of this issue, said Dr. Alan Waxman of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Under current rules, PET studies cannot be reimbursed by Medicare until chemotherapy is completed.

By Eric BarnesAuntMinnie.com staff writer

June 27, 2001

Click here to post your comments about this story. Please include the headline of the article in your message.

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com