"The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper'd pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side,

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound."

William Shakespeare, "As You Like It"

Andropause, a term used to describe the effects of sagging hormone levels in aging men, is of fairly recent coinage. Yet the effects of age-related hypogonadism were noted long before the advent of trophy wives and ill-considered Ferraris.

In recent years the question has centered on whether it is appropriate to intervene in the aging process, a debilitating yet entirely normal phenomenon. Organizations such as the Life Extension Foundation consider normal hormonal declines -- and indeed aging itself -- as diseases to be controlled and conquered. At the same time, traditional medicine hesitates to define aging as a disease, and endocrinologists haven't yet defined the androgen levels that signify clinically relevant hypogonadism for a given age.

But androgens do decline significantly in later life, and some men choose to compensate with injections, gels, or patches containing that most male of compounds, testosterone. What hadn't been studied until now is how testosterone supplementation plays out in the brain.

So at last week's Society of Nuclear Medicine conference in Toronto, Dr. Nicholas Friedman from the Hines VA Medical Center in Hines, IL, described a cerebral SPECT study that mapped the results of testosterone therapy in older patients, and found marked results.

"While aging is an inescapable fate for all of us, we're aware that some of us age well while others seem far older than their years," Friedman said. "I hope to share with you our findings about perfusion imaging in grumpy old men."

Declining androgens

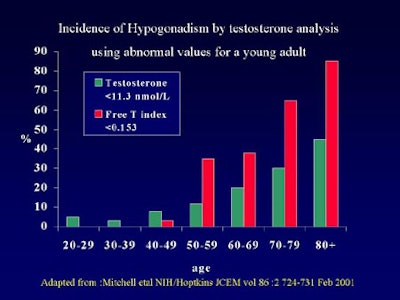

Compared to young adults, the free testosterone level in the average male has declined 30% by age 60, and 50% by age 80, Friedman said. Thus by age 60, a high proportion of males are hypergonadal, either by the measure of total testosterone, or free testosterone, both of which are difficult to measure and interpret.

|

"Endocrinologists say that a clinically relevant low-normal range in the older population is yet to be defined. So ... andropause has now become the new term to define the symptom complex associated with androgen deficiency," Friedman said.

The symptoms range from decreased lean body mass to decreased bone mineral density, as well as anemia, dysphoria (depression and "grumpiness"), decreased sleep and intellectual capacity, hair/skin changes, and decreased libido and erectile function.

There's even a testosterone quiz at www.tquiz.com, Friedman said.

"Don't worry -- if you can remember the address you don't need to take the test," he quipped. "If you can't, just write it down."

A review of the literature yielded nothing on the cerebral effects of testosterone therapy in men, Friedman said, though he found a study by Flink et al that found that increasing serum testosterone in rats corresponded with acutely higher seratonin transporter levels in the Raphe nuclei and 5-HT receptors and other higher serotoninergic sites in the cortex (Behavioral Brain Research, Nov. 1999, 105(1) pp. 53-68).

Another study by Moses et al found that estradiol and progesterone administration in older women produced generalized increased binding, especially in the anterior cingulate gyrus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and lateral orbitofrontal cortex (Biological Psychiatry, Oct. 2000, Vol. 48(8), pp. 854-60).

The SPECT study

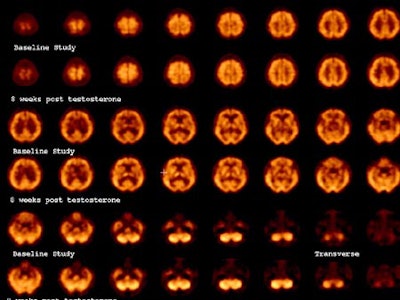

"Our study sought to determine whether SPECT imaging could identify changes in cerebral perfusion as a result of testosterone therapy," Friedman said. "We designed the study in a longitudinal fashion, to see whether these changes are constant or whether they change with time."

The team enrolled 9 males, aged 58 to 72, with documented low testosterone levels of 29.5 ± 5.8 pg/ml free early morning testosterone levels (compared with normal levels of 50-210 pg/ml). The subjects had been referred by an endocrinologist, and candidates with a history of prostate cancer, benign prostate hypertrophy, or cerebrovascular disease were excluded.

All subjects underwent therapy with 200 ml of testosterone enanthate by intramuscular injection every two weeks. Each patient completed an ADAM (androgen deficiency in aging males) questionnaire before and after therapy.

SPECT studies were acquired with a triple-head gamma camera using UHR fanbeam collimation (120 steps @ 50 sec/step), following administration of 25 mCi of Tc-99m HMPAO. The images were processed by data rebinning, without attenuation correction, and using a Hanning filter with a cutoff of 0.9 cyc/cm. The data was converted to the Mayo Analyze format, and imported into SPM96 analysis software. The images were analyzed visually, and the readers were blinded to the results of the SPM analysis, Friedman said.

In all, 7 patients completed the study, which included baseline scanning followed by repeat scans at 3-5 weeks and 3-4 months.

|

Friedman also noted some limitations: that the number of subjects was small, and that intramuscular injection was used rather than a transdermal patch, which would have provided a steady state of testosterone. No placebo was used. And the researchers could not determine whether testosterone or its derivatives are the active agents behind the changes, which will be addressed in the next phase of the study, Friedman said.

In an e-mail to AuntMinnie.com, Friedman offered a possible explanation of the results.

"It is difficult to make the leap from perfusion imaging to a theoretical concept, but the animal evidence and the findings in our perfusion imaging study suggest that as a result of testosterone replacement we are seeing changes in the serotoninergic system, with activation of the serotoninergic nuclei in the midbrain and activations in cortex via the serotoninergic system," he wrote. "While I cannot prove this, perhaps researchers with access to sertonin transporter or receptor ligands can examine this in the future."

Finally, Dr. Thomas Stuttaford offered unique insight into the condition ("Men Aging Badly," The Times, 1999), Friedman said.

"'... in the andropause, the physical and mental symptoms follow the slow decline in the testosterone levels in the blood. It starts to erode male confidence at about 45-55, just in time to confirm all those unfounded fears of the earlier mid-life crisis.'"

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 6, 2001

Click here to post your comments about this story. Please include the headline of the article in your message.

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com