The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the first clinical trial of a new technology that uses radiolabeled nanoparticles to brighten cancer cells so they can be detected by a PET-optical imaging camera.

Researchers from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) and Cornell University are collaborating with Hybrid Silica Technologies, a Cornell start-up company, and Dutch optical imaging developer O2view on the project and clinical trial.

The FDA's investigational new drug (IND) approval for the study represents the first inorganic particle platform of its class to be used for multiple clinical indications, according to co-researcher Dr. Michelle Bradbury, a neuroradiologist at MSKCC and assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College.

The trial will explore the applications of cancer targeting and future therapeutic diagnostics, as well as cancer disease staging and tumor burden assessment through lymph node mapping.

Multiple applications

"Cancer has largely been the heavy hitter for nanoparticle probes, and I think there are overlaps with other diseases where institutions could make use of such types of particles," Bradbury told AuntMinnie.com. "We are developing the [therapeutic diagnostic] probes and using them for surgical applications, mainly lymph node mapping."

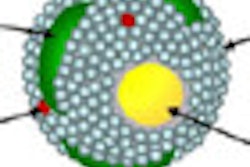

The so-called "Cornell dots" are silica spheres approximately 6 nm in diameter that enclose several dye molecules. The silica shell, which is essentially glass, is chemically inert and small enough to pass through the body and exit in the urine. For clinical applications, the dots are coated with neutral molecules -- polyethylene glycol (PEG) -- so the body will not recognize them as foreign substances and activate a patient's immune system to reject them.

To make the nanoparticles adhere to tumor cells, organic molecules that bind to tumor surfaces or specific locations within tumors can be attached to the PEG shell. When exposed to near-infrared light, the dots become brighter and help identify the targeted cancer cells.

Nanoparticle half-life

Nanoparticles in general can linger in the bloodstream for many hours and even days, depending on their size. Given their 6-nm size, the nanoparticles have a half-life of approximately six hours in the bloodstream before evacuation through the kidneys. "Within a 24-hour period," Bradbury said, "50% may be cleared through the kidneys."

Among the researchers' goals in this trial is to validate the pharmacokinetics and dosimetry of the nanoparticles and PET-optical imaging technology for safe use in humans. Researchers also will collect blood and urine samples to see how different parts of the body, besides organs, react to the nanoparticles.

The study will include five metastatic melanoma patients as its first enrollees. "If all goes well with a few patients, we hope to proceed with a targeted study," Bradbury said.

Surgical information

The technology, the researchers believe, could be particularly beneficial during surgical treatment, allowing surgeons to see the invasive or metastatic spread to lymph nodes and distant organs and illustrating the extent of treatment response.

Initially, the surgical applications will include cancer within the complex area of the head and neck. With the help of the nanoparticles and PET-optical imaging camera, surgeons will be able to detect the activity of the lymph nodes.

Currently, Bradbury explained, physicians have little or nothing to refer to during surgery other than a preclinical scan -- and compared to the scan, the patient is now in a totally different position on the table.

"How would they know where they are in the neck?" she asked. "They just don't [know], so they want tools so they can see what they are doing and see the nodes in relation to vital structures, such as nerves. They don't want to pick up activity from a lymph node plus an adjacent tumor, which would be easy to do, if you don't know where you are exactly."

Nanoparticles in mice

Researchers have already had some success with the nanoparticles and the PET-optical imaging technology in a preclinical study in mice. Among the conclusions is that the nanoparticles have been "optimized for efficient renal clearance" and "concurrently achieved specific tumor targeting" (Journal of Clinical Investigation, July 2011, Vol. 121:7, pp. 2768-2780).

In addition, the multimodal silica nanoparticles exhibit "what we believe to be a unique combination of structural, optical, and biological properties," wrote lead study authors Dr. Miriam Benezra and Dr. Oula Penate-Medina and colleagues.

To be clinically successful, the group added, the "next generation of nanoparticle agents should be tumor selective, nontoxic, and exhibit favorable targeting and clearance profiles. Developing probes meeting these criteria is challenging, requiring comprehensive in vivo evaluations."