Radiologists and nuclear medicine physicians recommended additional imaging tests about 30% of the time as a follow-up to oncologic PET/CT scans, with approximately half of those recommendations being unnecessary, according to a new study presented on Friday at the American Roentgen Ray Society (ARRS) meeting in Vancouver.

The researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston identified 84 requests for additional imaging tests and, after review, determined that 43 follow-up scans (51%) were not needed.

Furthermore, no adverse patient outcomes would have occurred from disregarding those 43 recommendations, said study co-author Dr. Atul Shinagare, who presented the results at the ARRS meeting.

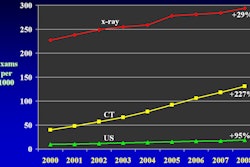

"The recommendations for additional imaging tests in radiology reports have reportedly doubled since 1995, and while often useful, they also increase healthcare costs, patient anxiety, and inconvenience, as well as the risk of complications associated with unnecessary tests and procedures," Shinagare told AuntMinnie.com.

Based on existing literature and their own experiences, Shinagare and colleagues knew that additional imaging tests are common in oncologic PET/CT reports. "However, the exact incidence and clinical significance of additional imaging tests, as well as the result of limiting or ignoring the additional imaging tests in this population, is unknown," he added. "Therefore, we decided to investigate this topic."

PET/CT review

The retrospective study analyzed 250 consecutive patients who received an oncologic PET/CT scan in 2008. Patient records that contained additional imaging tests were reviewed by two blinded readers. The pair recorded PET/CT results that prompted additional imaging tests, the appropriateness of those additional scans, the number of extra tests resolving the PET/CT question, and the clinical outcome of the findings from the additional exams. Clinical outcome was confirmed through pathology, unequivocal imaging progression, or imaging stability for at least 12 months.

The researchers identified 84 recommended additional imaging tests for 88 PET/CT scans in 74 (30%) of the 250 patients. Of those 84 additional scans, 43 (51%) were ruled inappropriate by the two reviewers. Shinagare and colleagues found 26 recommendations (31%) that prompted further imaging; these additional scans helped resolve inconclusive results in 20 (77%) of the 26 cases.

Shinagare said he and his colleagues did not expect the total to be as high as 30%. Although the researchers anticipated that the frequency of additional requests would vary by reader, there was no statistical difference among the readers for a couple of reasons.

"One [reason] is that PET/CT at our institution is interpreted through joint reading sessions involving one attending nuclear medicine physician and one attending diagnostic radiologist," he said."As a result, it was not possible to accurately ascribe additional imaging tests to one of these readers, even though one of the two readers may have been primarily responsible for the additional imaging tests. Additionally, there were a large number of PET/CT readers involved, both from nuclear medicine and diagnostic radiology, which further limited the ability to discern trends among readers."

Clinical insignificance

Perhaps most noteworthy, Shinagare and colleagues found that results from the additional imaging tests were clinically significant for only 10 patients (11%). Referring clinicians did not follow 58 (69%) of the recommendations for additional imaging; of the 58, only three (5%) were clinically significant. In addition, of the 43 recommendations considered inappropriate by the reviewers, only two (5%) were clinically significant. The PET/CT results were sufficient for diagnosis or management in each of these cases, according to the authors.

Based on the findings, three questions seem to address most of the inappropriate requests for additional imaging, according to Shinagare: Was the initial PET/CT sufficient for diagnosis or guiding management, was the finding stable on studies for more than 12 months without suspicious features, and would pursuing the finding potentially alter the management or prognosis?

While there is a subjective component to the study results and individual opinions may vary in some cases, Shinagare said, "we can definitely decrease the additional imaging tests by following this approach and rationally considering the necessity for additional imaging tests."

Brigham and Women's, for example, has changed its imaging protocols regarding additional tests through ongoing education for radiologists and nuclear medicine physicians, he said. Anecdotally speaking, he speculated that the incidence of additional imaging tests in oncologic PET/CT reports has decreased at the facility, though the numbers have not been formally measured.

"Nuclear medicine physicians and radiologists can significantly reduce the number of unnecessary additional imaging tests through thoughtful consideration of [their necessity] in view of the patient's clinical context and any anticipated added benefit of the additional imaging test," he added.

"There is a greater chance that the nonimaging community may exert increasing control over imaging tests unless we try to limit the unnecessary tests ourselves," Shinagare said. "Our knowledge of added benefits of various imaging tests certainly puts us at an advantage in judging the benefit of additional tests, and we should use this to limit the unnecessary imaging tests."

Shinagare and colleagues are considering a prospective follow-up study to evaluate the change in incidence of recommendations for additional imaging as a result of their study, and to assess the potential for a decision-support module to appropriately reduce the number of additional tests.