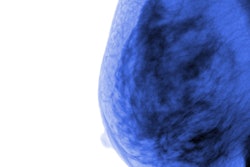

Breast density and its influence on a woman's breast cancer risk has become a hot topic for research and practice -- especially because more than 40% of screening-eligible women have dense tissue. Because density can limit conventional mammography's performance, clinicians have begun to use other modalities to screen for cancer, such as ultrasound and digital breast tomosynthesis.

But there's an unsung hero in breast cancer detection for women with dense tissue, according to research presented at the recent RSNA 2015 meeting: molecular breast imaging (MBI).

Carrie Hruska, PhD, from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN.

Carrie Hruska, PhD, from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN.Why? Because unlike 2D and 3D mammography, which image anatomy, MBI images tumor function by examining uptake in breast tissue of a technetium-99m (Tc-99m) radiotracer, presenter Carrie Hruska, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, told session attendees. It's a good supplemental option for women who have dense breast tissue on mammography, and it's a viable alternative for women contraindicated for MR.

MBI also costs roughly the same as a mammogram, it can be optimized for low-dose imaging, and, perhaps most importantly, it finds occult cancers that could have been missed after years of screening.

"Molecular breast imaging shows functional uptake of Tc-99m sestamibi in metabolically active cells, which is what cancer cells are," Hruska said. "When added to mammography, it finds an additional eight to nine cancers per 1,000 women screened -- and most of these are invasive."

Tracer uptake information

Are there particular features of an MBI exam that could help clinicians assess a woman's breast cancer risk?

Hruska and colleagues investigated this question by assessing background parenchymal uptake of Tc-99m sestamibi within normal fibroglandular tissue compared to fatty tissue. They gathered cases of 3,027 women who had undergone MBI exams between 2005 and 2014; 62 incident breast cancer cases were identified, of which 73% were invasive and 27% were ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). The group used Gamma Medica's LumaGem MBI unit.

The researchers also randomly selected 179 controls who were matched to the cancer cases in terms of age, date of MBI exam, menopausal status, and follow-up time. Classification of patients was based on background parenchymal uptake, with four categories established: photopenic, minimal-mild, moderate, or marked.

Hruska's group found that women with moderate or marked background parenchymal uptake at MBI had a 5.5 times greater risk of breast cancer than women with photopenic or minimal-mild background parenchymal uptake. These results were not affected by density or body mass index.

"Adding functionally based risk information from MBI could help identify women with dense breasts who are at greatest risk of breast cancer and who are most likely to benefit from tailored screening or prevention strategies," Hruska told session attendees.

What about dose?

In separate research to which Hruska contributed, presenter Zaiyang Long, PhD, also of the Mayo Clinic, shared results comparing the performance of a breast-specific gamma imaging (BSGI) system and an MBI system, using doses of Tc-99m sestamibi considered acceptable for low-dose imaging. The BSGI unit included a single-head multicrystal sodium iodide (NaI) system with a hexagonal-hole lead collimator, while the MBI device was comprised of a dual-head cadmium zinc telluride detector system with registered tungsten collimators.

Over distances of 1 cm, 3 cm, and 5 cm from the collimator, the MBI system demonstrated better spatial resolution than the BSGI system -- while yielding 2.6-fold greater sensitivity.

The other benefit of MBI is that in terms of radiopharmaceuticals needed for functional imaging, sestamibi is one of the safer ones, according to Hruska.

"MR uses gadolinium and contrast-enhanced mammography uses iodine, both of which carry risk of reactions in patients," she said. "Sestamibi is probably the safest agent of the three, and the radiation levels we're talking about are so low that the benefit of using MBI to find cancers mammography misses outweighs the hypothetical risk of increased radiation dose."

Barriers to MBI

So what gets in the way of more widespread use of MBI? Traditionally, nuclear medicine hasn't necessarily been incorporated into the breast imaging continuum, Hruska said.

"Some facilities don't even have nuclear medicine and mammography in the same building," she said. "At our institution, nuclear medicine works closely with breast imaging, so that's helpful."

In terms of reimbursement, coverage for MBI differs across the U.S. So even though the exam tends to be comparable in cost to a screening mammogram, if a woman has to pay out of pocket, that can be an obstacle.

But the technology may be such a good option for women with dense breasts that it makes overcoming these barriers worth it, according to Hruska. For example, when one woman with extremely dense tissue underwent MBI after years of negative findings on mammography, the MBI exam showed a 2-cm cancer that was completely occult on mammography.

"Interestingly, this patient had undergone a prior MBI exam eight years before this one, and I went back to take a look at it," Hruska said. "It showed that high background parenchymal uptake that we now know to be associated with risk, even then. This just supports our hypothesis that functional imaging can depict important biomarkers of breast cancer development years before they are evident on mammography."

Study disclosures

Hruska has an institutional license agreement with Gamma Medica.