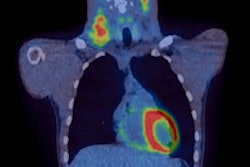

By using FDG-PET to guide chemotherapy, oncologists can significantly increase the number of patients who go into remission and decrease the use of more toxic forms of chemotherapy in those with advanced Hodgkin's lymphoma, according to a study published online April 11 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The findings come from four groups of researchers who collaborated on a phase II clinical trial that used FDG-PET to assess therapy for stage III to IV Hodgkin's lymphoma (JCO, April 11, 2016).

The study evaluated 331 patients with Hodgkin's disease between July 2009 and December 2012, who volunteered for two rounds of chemotherapy with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) after their diagnosis of cancer. The patients were then scanned with PET to determine their response to the initial treatment.

If the scan results were negative and the cancer appeared to be gone, the patients received a final four cycles of ABVD. Those whose scans showed positive signs of Hodgkin's disease were given six cycles of chemotherapy with a seven-drug combination of bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (eBEACOPP), which is typically used in Europe.

The eBEACOPP treatment comes with risks that include infertility, sustained heart or lung damage, and the development of secondary cancers such as leukemia.

The researchers found that 64% of patients who received eBEACOPP were cancer-free after two years, which is more than double the expected remission rate for this patient group. Typically, among those who receive two rounds of ABVD and have a positive PET scan, approximately 15% to 30% are cancer-free after two years.

Those who received only ABVD and had a clear PET scan fared the best, with 82% being free of cancer after two years.

Only 20% of the patients in the trial were treated with the powerful eBEACOPP regimen and thus also exposed to its potential adverse effects, noted co-author Dr. Jonathan Friedberg, director of the James P. Wilmot Cancer Institute at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

This finding is important because many people diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma are in their 20s and 30s and want to have children. This response-adapted therapy would ensure that those who need the more toxic drugs receive them, while others could be spared from infertility and serious toxicities, he added.

Contributing to the research were the Southwest Oncology Group, the Cancer and Leukemia Group B/Alliance, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, and the AIDS Malignancy Consortium.