By turning to a SPECT/CT scan with technetium-99m (Tc-99m) sestamibi, clinicians can overcome inconclusive or suspicious CT or MRI results and are better able to characterize and diagnose renal cell carcinoma, according to a study published in the April issue of Clinical Nuclear Medicine.

The uptake of Tc-99m sestamibi by oncocyte tumors is the key differentiator between benign and malignant lesions. The informed prognoses can help spare patients from unnecessary biopsies or surgery that could lead to partial or complete kidney removal and possibly dialysis.

"How you tell the pussycat from the tiger has been elusive by radiology in the past," said co-author Dr. Mohamad Allaf, a professor of urology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "[SPECT/CT] is noninvasive, it is not expensive, and does no harm to patients in any way. It really adds value to the proposition of care for patients with a kidney tumor."

Diagnostic challenges

Preoperatively diagnosing renal cell carcinoma has been a challenge for clinicians. Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI have had difficulty in characterizing and differentiating between malignant and benign renal tumors, which could lead to unnecessary biopsies and/or radical nephrectomy, the authors noted (Clin Nucl Med, April 2017, Vol. 42:4, pp. e188-e193).

Dr. Mohamad Allaf from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Dr. Mohamad Allaf from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.Kidney procedures are especially onerous for older patients who have only one kidney or insufficient renal function. Removing all or part of the kidney could require patients to undergo dialysis, potentially causing complications to magnify.

"We could biopsy some of these tumors, but some of them are not in the right place and are not amenable to a biopsy," Allaf said. "They are in the front part of the kidney, or they are difficult to get to."

In addition, he estimated that 15% to 20% of the time, a patient with a negative biopsy still has cancer.

Tc-99m sestamibi is commonly used to image the heart and is designed, in part, to highlight the organ's mitochondrial content. The most common benign lesion -- and the one that mimics kidney cancer on MRI, CT, and ultrasound -- is the oncocyte tumor. Oncocytoma also contains mitochondria, but renal cell carcinoma is relatively devoid of mitochondria, which creates energy for the cell.

Thus, the Johns Hopkins researchers hypothesized that Tc-99m sestamibi uptake could be a key indicator for mitochondria in the kidney to differentiate between malignant and benign tumors.

"If we remove the tumor and it is benign, most of the time it is an oncocyte tumor," Allaf said. "If we had known this, we may have been able to save the kidney, or we may have not done anything, because the patient is older. If it were a benign tumor, then we would just watch it."

The researchers prospectively reviewed 48 patients (age range of 40-81 years) with known oncocytoma who underwent conventional CT, contrast-enhanced MRI, or noncontrast-enhanced MRI. The mean size of the oncocyte tumors was 2.95 cm. Eight weeks later, the subjects underwent SPECT/CT scans (Symbia, Siemens Healthineers) with 925 MBq of Tc-99m sestamibi prior to partial or radical nephrectomy.

Two experienced radiologists were blinded to SPECT/CT and surgical pathology results, and they were asked to rate their diagnostic confidence on a five-point scale, with 1 as definitely benign and 5 as definitely malignant. They also were asked to calculate Tc-99m sestamibi uptake within the tumors.

Based on surgical results, 39 tumors were malignant renal cell carcinomas, while there were nine benign tumors (six oncocytomas, two oncocytic/chromophobe tumors, and one angiomyolipoma).

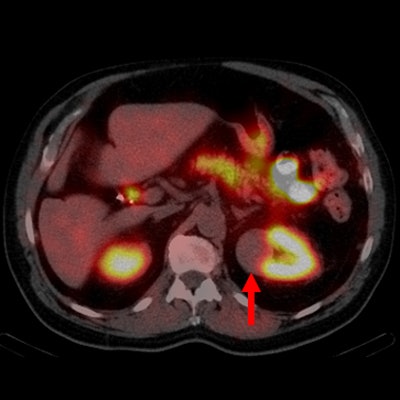

Hot and cold spots

The SPECT/CT images showed noticeable uptake of Tc-99m sestamibi, or "hot spots," in the mitochondria, indicating a benign oncoctye tumor. Conversely, the malignant tumors displayed no such uptake of the tracer, or "cold spots," suggesting malignancy.

"The cancer itself does not have mitochondria. If the sestamibi is 'cold,' it is confirmed to me that the patient has kidney cancer," Allaf said. "And if [the sestamibi] is hot, then I become more suspicious that they have an oncocytoma, and the discussion with the patient goes more toward a benign tumor."

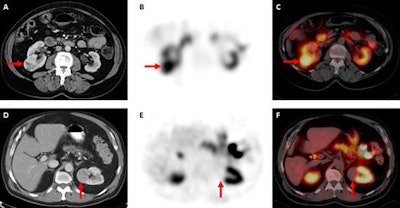

Axial contrast-enhanced CT image (A) demonstrates an enhancing mass in the lateral right kidney (red arrow). Tc-99m-sestamibi axial SPECT (B) and axial SPECT/CT images (C) show intense radiotracer uptake in the right kidney mass (red arrows), which is typical in oncocytomas and other benign/indolent neoplasms such as hybrid oncocytic/chromophobe tumors. Axial contrast-enhanced CT (D) shows an enhancing mass in the medial aspect of the left kidney (red arrow). Tc-99m-sestamibi axial SPECT (E) and axial SPECT/CT (F) images show complete photopenia in the mass (red arrows), which is typical with clear cell renal cell carcinomas. Images courtesy of Drs. Steven Rowe, Mohamad Allaf, and Michael Goren.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT image (A) demonstrates an enhancing mass in the lateral right kidney (red arrow). Tc-99m-sestamibi axial SPECT (B) and axial SPECT/CT images (C) show intense radiotracer uptake in the right kidney mass (red arrows), which is typical in oncocytomas and other benign/indolent neoplasms such as hybrid oncocytic/chromophobe tumors. Axial contrast-enhanced CT (D) shows an enhancing mass in the medial aspect of the left kidney (red arrow). Tc-99m-sestamibi axial SPECT (E) and axial SPECT/CT (F) images show complete photopenia in the mass (red arrows), which is typical with clear cell renal cell carcinomas. Images courtesy of Drs. Steven Rowe, Mohamad Allaf, and Michael Goren.With the addition of Tc-99m-sestamibi SPECT/CT results, the readers' diagnostic certainty increased in 14 cases (29%) in classifying nine benign lesions and five malignant lesions. Tc-99m sestamibi also changed nine initial diagnoses of malignancy to a benign tumor. Postsurgical pathology confirmed a diagnosis of benign histology in seven of those cases and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma for the other two lesions.

Tc-99m sestamibi also elevated the readers' diagnostic confidence level to determine that five cases had malignancies, all of which were confirmed as renal cell carcinoma on surgical pathology.

Clinical practice

Clinicians at Johns Hopkins are currently using this approach as an adjunct to an inconclusive CT or MRI scan, or when there is a suspicious renal mass and the patient might have an oncocytoma.

"Clinically speaking, someone gets a CT image and it is read as a solid renal mass, which is suspicious for renal carcinoma," Allaf said. "The next step is usually to see a urologist and reflexively to recommend surgical treatment, because we did not have anything else to further characterize it. Now, a Tc-99m-sestamibi scan would add value and prevent surgery from being necessary in a good number of these cases."

The researchers have expanded the study to approximately 140 patients to further validate the results. The long-range objective is to share the findings and the strategy to clinicians around the world. In fact, numerous inquiries already have been received about how to interpret the radiopharmaceutical-enhanced SPECT/CT scans.

Allaf and colleagues also are scheduled to conduct a seminar on the merits of the imaging technique in May at the American Urological Association annual meeting in Boston.

"Understandably, people want to see more research about this before they widely adopt it, but I do believe that this will hopefully take off," Allaf said.