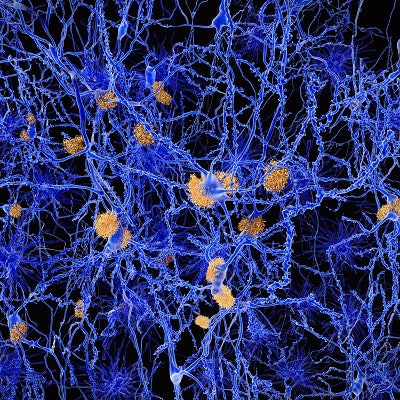

Elevated levels of amyloid on PET scans of the brain have been associated with an increased risk for Alzheimer's disease (AD). But a study published June 13 in the Journal of the American Medical Association suggests that higher levels of amyloid could actually be the first preclinical sign of the illness.

Patients with elevated brain amyloid levels on a baseline PET scan were more than twice as likely to have developed symptoms consistent with Alzheimer's disease at four-year follow-up, compared with those with normal amyloid levels, according to a team led by Michael Donohue, PhD, from the University of Southern California.

If elevated brain amyloid in cognitively normal people indicates a presymptomatic stage of disease, it's possible that patients could receive intervention earlier -- and payors could be persuaded to cover PET scans for the evaluation of amyloid levels, Donohue told AuntMinnie.com. Currently, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) only pays for these scans as part of clinical studies.

"It's exciting to get this long-term perspective on the course of Alzheimer's disease, and our study supports the idea that we may be able to perform interventions in the preclinical stages," he said.

Risk factor, or marker of early disease?

A diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease requires the presence of dementia with impairment of multiple cognitive processes -- enough to interfere with daily activities, Donohue and colleagues wrote. This dementia is often preceded by mild cognitive impairment that doesn't necessarily affect a person's function. Previous research has suggested that mild cognitive impairment, when accompanied by biomarkers of Alzheimer disease such as elevated brain amyloid, should be considered a risk factor for AD (JAMA, June 13, 2017, Vol. 317:22, pp. 2305-2316).

Michael Donohue, PhD, from the University of Southern California.

Michael Donohue, PhD, from the University of Southern California.In the current study, Donohue's group sought to address the question of whether this combination of mild cognitive impairment and elevated brain amyloid is actually the beginning of the disease, not just a risk factor. To this end, the team gathered cognitive and biomarker data from 445 patients who were participating in the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). The patients were observed from August 2005 to June 2016, with a median follow-up of 3.1 years.

Using PET imaging or a cerebrospinal fluid assay of beta amyloid, the researchers classified 243 patients as having normal brain amyloid and 202 as having elevated brain amyloid. The mean age of the patients was 74, and 52% were women.

The participants underwent two PET studies: one with FDG to measure glucose metabolism in the brain, and another with either florbetapir or Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) to measure brain amyloid levels. They also had a series of cognitive tests, including the Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite (PACC), the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), and the Logical Memory Delayed Recall.

Overall, compared with patients who had normal amyloid at baseline, those with elevated amyloid had worse mean scores at four years on the PACC, MMSE, and CDR-SE tests. Differences in scores between the groups for the Logical Memory Delayed Recall test were not statistically significant.

Specifically, at four years, 32.2% of patients who had elevated amyloid levels at baseline had developed AD symptoms, compared with 15.3% of patients with normal amyloid levels. At 10 years of follow-up, 88.2% of those with elevated amyloid levels had developed AD symptoms, compared with 29.4% of those with normal amyloid.

Next steps

There are currently no effective treatments for preclinical Alzheimer's disease, Donohue and colleagues wrote. The value of diagnosing earlier may be in education and planning for patients and their families.

"Therapeutic trials are now underway to assess whether the prognosis of preclinical AD can be altered by interventions targeting amyloid," the group wrote. But treatment "of preclinical AD with antiamyloid or other interventions, if shown to be effective, would represent management of disease rather than risk reduction."

Randomized trials are needed to evaluate how interventions based on the study's findings would affect the course of Alzheimer's, Donohue concluded.

"We still have a lot to learn about the early stages of the disease, and we need to conduct further research to assess these findings," he said.