PET/MRI scans with novel radiotracers indicate that young athletes may suffer from long-term neurodegeneration after experiencing multiple sports-related brain injuries, according to a recent study by a group of Swedish researchers.

The group observed increased uptake of both tau tracer THK5317 and the neuroinflammatory tracer PK11195 up to two years after injury in athletes with three or more sports-related concussions and in patients with moderate-severe traumatic brain injuries (TBI). The findings suggest the initial injuries may increase the long-term risk of neurodegeneration.

"This is the first tau PET study evaluating TBI patients and [sports-related concussion] athletes in such young cohorts," wrote lead author Dr. Niklas Marklund, PhD, and colleagues of Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden.

Impacts to the brain in sports-related concussions and TBIs elicit processes that contribute to delayed axonal injury and initiate neuroinflammation, which researchers believe stimulates the aggregation of tau. Since most evidence for this hypothesis is obtained from autopsy and experimental studies, however, methods to monitor neuroinflammation and tau aggregation in vivo are needed, the authors wrote.

In this study, published April 7 in NeuroImage: Clinical, Marklund and colleagues used PET/MRI to investigate patients who had experienced injuries playing soccer, ice hockey, or alpine skiing. They recruited nine healthy controls between the ages of 20 and 34, 12 symptomatic athletes who experienced sports-related concussions between 20 and 43 years old (6 males, 6 females), and six moderate-to-severe TBI patients between 21 and 40 years old (4 males, 2 females).

Compared with controls, individuals with TBI and sports-related concussions had lower scores on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) test, a battery of tests administered to assess cognitive changes (p < 0.05). In TBI patients, CSF and plasma neurofilament light chain (NFL) concentrations were increased (p < 0.05).

In athletes with sports-related concussions, increased neuroinflammation was observed on PET in medial temporal lobes, and tau aggregation was observed in the corpus callosum. In TBI patients, widespread white matter tau aggregation and neuroinflammation were found.

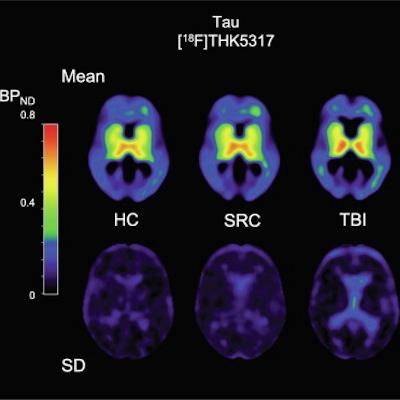

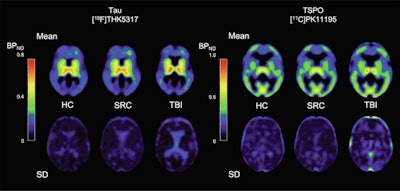

Image shows mean THK5317 and PK11195 nondisplaceable binding potential (BPND) for controls, rSRC and TBI patients, depicting tau and translocator protein (TSPO) expression, as well as corresponding standard deviation images. In symptomatic rSRC athletes, a voxel-wise t-test showed clusters of significantly increased THK5317 binding in the corpus callosum and subcortically including the medial temporal region and PK11195 binding in the medial temporal lobes. In TBI, elevated tau and TSPO binding was observed in the thalamus, temporal lobe white matter and midbrain. Significant group differences in total tau load were found between healthy controls and rSRC in subcortical gray matter (SRC 7.5 ± 0.9, controls 6.7 ± 0.5, p = 0.038), although not between TBI patients and controls. No significant differences in the number of voxels with THK5317 BPND > 0.5 or skewness in BPND distribution were found. Image courtesy of NeuroImage: Clinical.

Image shows mean THK5317 and PK11195 nondisplaceable binding potential (BPND) for controls, rSRC and TBI patients, depicting tau and translocator protein (TSPO) expression, as well as corresponding standard deviation images. In symptomatic rSRC athletes, a voxel-wise t-test showed clusters of significantly increased THK5317 binding in the corpus callosum and subcortically including the medial temporal region and PK11195 binding in the medial temporal lobes. In TBI, elevated tau and TSPO binding was observed in the thalamus, temporal lobe white matter and midbrain. Significant group differences in total tau load were found between healthy controls and rSRC in subcortical gray matter (SRC 7.5 ± 0.9, controls 6.7 ± 0.5, p = 0.038), although not between TBI patients and controls. No significant differences in the number of voxels with THK5317 BPND > 0.5 or skewness in BPND distribution were found. Image courtesy of NeuroImage: Clinical.Ultimately, the results showed that PET tracers for tau and neuroinflammation can be used to identify long-term, postinjury increases in tau aggregation and microglial activation in young, symptomatic athletes with a history of three or more concussions, as well as in young adult patients with a single moderate-severe TBI. The data imply persistent pathology at prolonged postinjury time points and are supported by the increased CSF and serum NFL levels, the authors wrote.

The researchers emphasized that while a correlation between closed-head impact and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) has been suggested in numerous reports, their study was not an investigation of CTE. No athlete with sports-related concussion in the study experienced personality changes, dementia, or aggression, traits associated with CTE.

Previous PET and autopsy studies have evaluated older individuals with more extensive postinjury times. While many details remain unknown, tau pathology may be the mechanistic link to cognitive symptoms and the tau aggregation observed in this study may be progressive, the authors concluded.

"Extended clinical follow-up, biomarker examinations, and renewed PET imaging are needed to determine whether these findings exacerbate over time or if spontaneous resolution is possible," they wrote.