Nuclear medicine's best bet to attract more physicians to the field may be to get its hooks into residents interested in recent clinical advances, according to a study published September 1 in Academic Radiology.

A group of specialists in Boston surveyed a group of current U.S. radiology residents -- those pursuing nuclear medicine and those who aren't -- to identify key factors in their career choices. Research was the least attractive aspect of nuclear medicine, while routinely encountered clinical pathology was the most attractive, they found.

"Rising demand for [nuclear medicine/molecular imaging] physicians in the near future is anticipated -- therefore, successful recruitment of talented and enthusiastic trainees into the field is a high priority," wrote corresponding author Dr. Bashar Kako, a radiology clinical fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, and colleagues.

Although the number of nuclear medicine trainees and training programs has declined over the past 15 years, the trend has plateaued or slightly increased within the last four years, with a total of 84 trainees (residents and fellows) in 2020-2021, according to the authors.

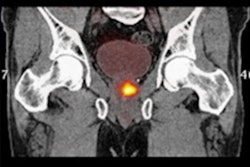

Advances in nuclear medicine -- the U.S. approvals of F-18 DCFPyL and gallium-68 PSMA-11 radiotracers for use in prostate cancer patients, for instance -- are increasing use of diagnostic and therapeutic nuclear medicine in clinical practice, and new crops of physicians will be needed to handle the increase in volume, the authors wrote.

Given this backdrop, the researchers aimed to identify key factors that may attract more trainees into the field. They sent a web-based survey containing multiple-choice questions to all diagnostic radiology residency programs in the U.S. between February 21, 2021, and April 4, 2021. They received responses from 198 residents.

Over half of the trainees (58.6%) reported first learning about nuclear medicine during medical school and 27.3% first learned about the specialty during radiology residency, with no significant difference between trainees specializing in nuclear medicine and those who were not, according to the findings.

Routinely encountered clinical pathology was the most attractive aspect of nuclear medicine (29.4%) for those going into the field, which is notably different from the response of those not specializing in nuclear medicine (9.8%), the researchers found.

In contrast, respondents reported that nuclear medicine-associated research was overall one of the less motivating aspects for pursuing the career. A higher proportion of respondents specializing in the field (35.3%) stated that research was the least attractive aspect, as compared with those not specializing.

"While scientific research and discoveries of [nuclear medicine/molecular imaging] are often touted as one of its most exciting areas ... research was surprisingly the least attractive aspect," the group wrote.

In addition, a higher quality experience while on a nuclear medicine rotation including improved teaching and didactics was deemed the most important factor for attracting trainees into the field (38.9%), according to the survey responses.

Ultimately, it is unclear whether the lack of interest in research is due to the areas and topics available, its availability at the trainees' institutions, lack of free time to pursue it, or greater interest in the clinical aspects of nuclear medicine, the authors wrote.

Additional exploration is needed to clarify these questions further, they wrote.

However, according to this analysis of survey responses, improving exposure to nuclear medicine during medical school and providing more hands-on clinical experiences during residency training could result in greater interest, they suggest.

"This may widen the pool from which future [nuclear medicine/molecular imaging] trainees derive, whether it is through diagnostic radiology or otherwise," Kako and colleagues concluded.