Dear MRI Insider,

In 2003, 25-year-old Marquise Hudspeth was shot to death by police in Shreveport, LA. Authorities said they took the drastic action for two reasons: Hudspeth had been driving erratically and the cell phone he was brandishing resembled a gun (Shreveport Times, April 23, 2003).

According to the public outcry that followed the incident, there was a third, more insidious reason behind Hudspeth's violent death -- he was shot because he was black. His family filed a suit claiming that Hudspeth's civil liberties had been violated. A year later, the officers were cleared of any wrongdoing (Shreveport Times, March 24, 2004).

Unless the evidence is obvious, proving that someone is motivated by race, either negatively or positively, is a gray area. Behavorial science studies have shown that a person's expectations of another individual -- and whether that individual intends harm -- can be influenced by the latter's race.

Most recently, investigators from Florida State University in Tallahassee ran an experiment with 50 police officers in which a gun or neutral object (such as a cell phone) was superimposed onto a white or black face, and the officers had to decide in an instant whether to shoot or hold their fire. The early part of the trial revealed that the officers were likelier to mistakenly shoot at an unarmed black suspect than an unarmed white suspect. However, as the experiment progressed, the officers were able to control that bias (Psychological Science, March 2005, Vol. 16:3, pp. 180-183).

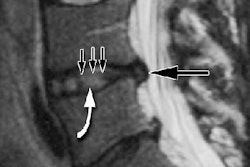

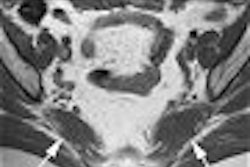

Even when we are confident that we're not blatantly assessing, judging, or discriminating against people because of the color of their skin, our brains may automatically be doing just that. In this MRI Insider Exclusive, we highlight the latest research on brain function and race processing. These functional MRI studies focused on the amygdala, which is the area responsible for sensing potential danger.

To some degree, evolution has hardwired us to be distrustful of "others." But personal experience goes a long way in determining if we truly see the world as black or white. To read more on this neuroimaging exploration of racial bias, click here.