Who or what is to blame for the trend toward eating disorders among women the world over? The fashion industry seems to simultaneously accept blame (banning models with a "low" body mass index from runways) while also denying culpability (supermodel Giselle pointing a slim finger at weak family structures).

Mixed messages about acceptable weight certainly abound in Hollywood as well. For example, in a recent issue of Us Weekly magazine, one article praised a group of actresses for shedding pounds after unloading their husbands/boyfriends, while another lauded "curvier" up-and-comers like Dreamgirls' Jennifer Hudson (February 19, 2007).

Even science offers provocative "nature versus nurture" arguments. A number of studies have suggested that some people are genetically predisposed to eating disorders such as bulimia and anorexia nervosa. Other researchers posit that a woman's relationship with her father may predispose her to eating disorders (American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, November 5, 2005, Vol. 139B:1, pp. 61-68; British Journal of Clinical Psychology, September 2006, Vol. 45:3, pp. 319-330).

Rather than assigning blame, perhaps the better questions to ask are what makes a person -- and women in particular -- susceptible to eating disorders and why? Is there something wired into our brains that drives this complex relationship with food, making it more than just a tool for mere survival?

In honor of National Eating Disorders Awareness Week, AuntMinnie.com surveyed the latest research in eating-related imaging. We start with a study of women without eating disorders that looked at appetite-related brain activity, followed by a separate paper on the subjective quality of appetite. Then we turned our attention to research on the cerebral processing of food-related stimuli and how it's affected by gender. Finally, we have the results of a study on hunger and satiety in anorexia patients.

Comfort me with (caramel-covered) apples

In the first study, a group from the Eastern seaboard correlated brain activity in the orbitofrontal cortex with mood ratings. In other words, they looked at whether there was a connection between a person's emotional state and the types of food that the person gravitated toward.

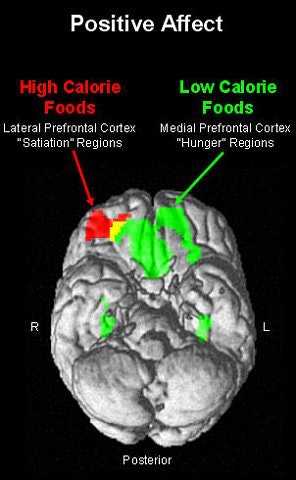

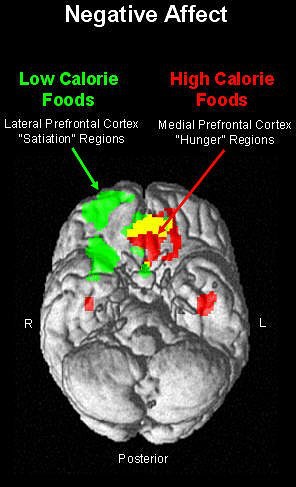

"The orbitofrontal cortex appears to be particularly important for evaluating reinforcement contingencies.... The experience of hunger and motivation to eat is associated with increased activity within the medial and caudal regions of the orbitofrontal cortex…. Lateral regions of the orbitofrontal cortex may serve as inhibitory function that leads the satiated individual to stop eating," wrote William Killgore, Ph.D., and Deborah Yurgelun-Todd, Ph.D., in the International Journal of Eating Disorders (July 2006, Vol. 39:5, pp. 357-363).

Killgore is from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, MD, while his co-author is from McLean Hospital in Belmont, MA.

For this research, 13 healthy women were enrolled. They were deemed free of any history of eating disorders, and were within normal limits of the body mass index (BMI). They did not consume any food for at least 90 minutes before undergoing blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) fMRI.

Echoplanar imaging (EPI) was done on a 1.5-tesla unit (LX, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, U.K.) and included matched T1-weighted images for anatomic localization. Pictures of food, such as vegetables (low-fat) and cake (high-fat) were presented during three separate scanning runs, along with neutral images (spoons). Immediately after imaging, the participants completed a 20-item self-report of their current affective state. The scale offered two scores, pleasant enthusiasm (PA) or unpleasant emotional activation (NA).

|

Images courtesy of Major William D. "Scott" Killgore, Ph.D.

|

According to the results, the images of high-fat foods yielded greater fMRI activity within the right lateral orbitofrontal cortex, which correlated with PA subjective ratings. On the other hand, greater activation was seen within the medial orbitofrontal and insular cortex, along with higher NA ratings, when the participant looked at low-fat foods.

These results indicate that "functional segregation of the medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex with regard to the motivation to eat," the authors stated, pointing out that the medial orbitofrontal cortex is associated with rewarding stimuli while the lateral orbitofrontal activity responds to punishing stimuli.

"The current findings … suggest that one mechanism of the relation between mood and appetite may involve the relative changes in brain activity within the lateral and medial orbitofrontal cortices," they wrote. As a result, people may go for high-fat foods in an effort to "self-medicate" their negative moods, the authors explained. Over a lifetime, this can lead to unhealthy food choices as a person's negative mood state drives her brain toward comfort foods, they added.

In a related study, European and U.S. researchers demonstrated that the putamen, an area of the brain credited with integrating cognitive and emotional response, was modulated by the feeling of appetite.

"In contrast to hunger, appetite is a psychological desire to eat food without any metabolic needs," explained Katarina Porubska from the MEG-Center at the University of Tubingen in Germany. Her co-authors are from the University Hospital Tubingen, the University of Arkansas in Little Rock, and the University of Trento in Italy. Furthermore, "there are three sensory modalities which influence our behavior in respect to food: gustatory, olfactory, and visual," they wrote (NeuroImage, September 2006, Vol. 32:3, pp. 1273-1280).

For their study, 12 normal-weight subjects, five of whom were female, were instructed not to eat at least five hours before the test. The stimulus set consisted of 128 color pictures of food and nonfood items. Whole-brain MRI on a 1.5-tesla scanner (Vision, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) was performed with a protocol that included functional T2*-weighted imaging and EPI.

As with the first study, the authors reported activation in the orbitofrontal cortex in response to the food images. They also found activation in the insular/opercular cortex bilaterally, the operculum, and the right putamen. All of these areas were modulated by the subjective feeling of appetite, they said, indicating that the insular cortex was involved in nongustatory processing of food.

While the study participants did not have eating disorders, their results can lead to a better understanding of these brain areas and how humans approach food control. "Especially interesting questions are connected to development and possible malfunctions of this network like eating disorders and to what extent this network is responsible for the increasing number of obese people," the authors stated.

Fast food

Investigators at the King's College Institute of Psychiatry in London went one step further in the study of how the brain regulates the desire for food, adding the variables of gender and a fasting state.

"Women are more prone to develop eating disorders, and gender differences in food preferences and in neurohumoral regulation of eating behavior have been observed," wrote Dr. Rudolf Uher, Ph.D., and colleagues in Behavioural Brain Research (April 25, 2006, Vol. 169:1, pp. 111-119).

Before undertaking this study to look at food-related information processing during fasting and satiety, the authors hypothesized that food-related cues would increase activation of an "orexigenic circuity, including the insular and orbitofrontal cortices." In addition, this reaction in the orexigenic circuitry would be greater in women.

Of the 18 healthy volunteers, 10 were women with a mean BMI of 22.5 kg/m². Before the fasting session, the participants were instructed not to eat or drink anything for 24 hours. Before the satiated session, they were asked to eat as usual and have a meal on the morning of the experiment.

BOLD MR imaging was done on a 1.5-tesla scanner while the subjects looked at pictures of food and nonfood objects. For the taste experiment, they were given liquid versions of chocolate milk and chicken broth. These liquid stimuli also had an olfactory component.

According to the behavioral measures, the subjective feeling of hunger increased during the fasting period, with women reporting greater hunger than men. Fasting also led to a significant worsening of mood and to elevated nervousness, especially in the female subjects.

On the MR studies, the authors noted widespread activations in men and women, particularly in the occipital, temporal, and frontal cortices. Both experiments elicited BOLD responses in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. When responding to chocolate milk, an area in the medial part of the lingual gyrus and left caudate nucleus demonstrated a response while chicken broth elicited a signal from the thalamus and the anterior parts of the lateral prefrontal cortex.

Broken down by gender, women showed a stronger response to visual food-related stimuli in the fusiform gyrus bilaterally. In the taste experiment, they showed a stronger response in the left anterior insula, the left frontal operculum, and the apical medial prefrontal cortex.

"These findings support our hypothesis that women would have greater reactivity to food-related stimuli…. Women also showed a greater increase in the subjective feeling of hunger with fasting," the authors explained. "This may be related to the greater sensitivity of females to humoral signals of hunger and satiation and may hint at a neural basis of gender differences in susceptibility to eating disorders."

These results from Uher and colleagues support previous studies showing that patients with eating disorders tend to have an obsessive, cognitive preoccupation with food. So what happens in the brain of an anorexic patient who has learned to severely restrict her food intake? Stephanie Santel and colleagues set out to find the answers.

Santel is from department of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University Magdeburg in Germany. Her co-authors are from the departments of psychology, neurology, and the Center for Advanced Imaging, all in Magdeburg.

They enlisted 12 anorexia nervosa (AN) patients and 10 healthy controls, all female. All the patients had a BMI below the 10th age-related percentile and were suffering from first-episode AN for less than a year. The AN group also showed symptoms of depression.

Again, the subjects looked at pictures of high-calorie foods as well as nonfood objects while being scanned in a 1.5-tesla unit (Horizon LX, GE Healthcare). Structural images were obtained with an RF-spoiled GRASS sequence. Functional imaging was performed using an echo-planar T2*-weighted gradient-echo sequence. Sessions were done before and after a meal.

Not surprisingly, the hunger score for AN patients was significant lower than that of the control group. AN patients also rated food stimuli as less pleasant than the controls. On fMRI, AN patients had diminished activation in the left inferior parietal lobe when satiated and diminished activation in the right lingual gyrus when hungry. These differences between hunger and satiation were absent in the control group, the authors reported.

"The present study demonstrates … that activation in the IPL (inferior parietal lobe) was correlated with specific behavioral and physical symptoms of AN: there was decreased IPL activation in participants with strong dietary restraint, weaker disinhibition of eating and lower BMI values," Santel's group wrote (Brain Research, October 9, 2006, Vol. 1114:1, pp. 138-148).

The postcentral gyrus of the IPL houses primary somatosensory neurons for the lips, teeth, and tongue. The decrease somatosensory-gustatory responsiveness in AN patients most likely facilitates fasting, the authors explained. It may also offer a reason why AN patients rated food stimuli as less pleasant than the healthy controls did.

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

March 2, 2007

Related Reading

Skinny teens warned about osteoporosis risk, February 2, 2007

BMD recovery after anorexia based on weight gain and menstrual function, August 23, 2006

Brain spot for body size perception identified, December 16, 2005

PET reveals more than body mass wasting away with eating disorders, September 15, 2005

Copyright © 2007 AuntMinnie.com