MRI offers a "robust method" for assessing suspected acute appendicitis in pregnant patients in a speedy 30 minutes, according to a group from Beth Israel-Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. In addition, the MR exam is the best bet for visualizing the normal appendix.

"Acute appendicitis is the most common cause of abdominal pain in pregnancy that requires surgical treatment," said Dr. Ivan Pedrosa in a talk at the 2007 International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) meeting in Berlin. "Although its incidence is low, it still remains a diagnostic challenge because of anatomy and histological alterations that occur during pregnancy."

These anatomic changes include superior displacement of the appendix because of the gravid uterus. As a result, the normal appendix may appear in the right midabdomen or right upper quadrant during the second and third trimesters, according to Pedrosa and colleagues (RadioGraphics, May-June 2007, Vol. 27:3, pp. 721-744).

Last year, Pedrosa's group published a paper on the value of MR in this patient population. At the time, they enrolled 51 pregnant women who received oral contrast before the MR exam was done in a supine position. According to the results, MR scans were positive for appendicitis in four patients and inconclusive in three (either the appendix was not seen or was borderline enlarged). They reported an overall sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 93.6%, and an accuracy of 94% (Radiology, March 2006, Vol. 238:3, pp. 891-899).

Those promising results were reiterated at the 2006 RSNA meeting in Chicago when Pedrosa presented data on 109 patients. As part of their imaging protocol, all pregnant women underwent ultrasound imaging as well. At the RSNA meeting, Pedrosa stated that the normal appendix was visualized in 89% of the patients on MR but not on ultrasound. In addition, MR correctly identified alternative causes of pain including ovarian torsion and ectopic pregnancy.

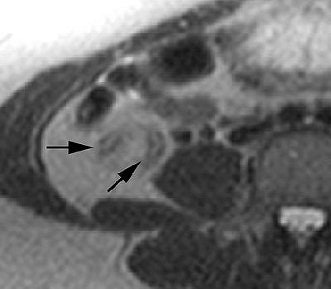

|

| Coronal single-shot fast spin-echo (SSFSE) image in pregnant patient with RLQ pain shows an enlarged blind-ending tubular structure (arrowheads) adjacent to the right kidney. Image courtesy of Dr. Ivan Pedrosa. |

At the ISMRM meeting, Pedrosa presented an update on their ongoing investigation, sharing results in 158 pregnant patients with suspected acute appendicitis. Of this group (group A), 122 underwent 1.5-tesla MRI followed by ultrasound (117) and CT (2). Thirty-six patients were examined with ultrasound and CT but not MRI (group B). The appendicitis/appendectomy rate (AAR), negative laparotomy (NLR), and perforation rate (PR) were calculated.

A minimum of one hour before the MR study, the patients received 300 mL each of ferumoxsil and barium sulfate. This oral contrast agent provided negative contrast within the bowel lumen and eliminated susceptibility artifacts, the group explained in Radiology.

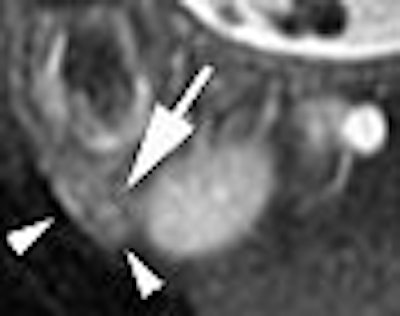

|

| Same patients as above. Axial fat-saturated SSFSE confirms the presence of periappendiceal edema as a rim of high SI (arrowheads) around the fluid-filled distended appendix (arrow). Surgery and pathology confirmed the diagnosis of uncomplicated acute appendicitis. Image courtesy of Dr. Ivan Pedrosa. |

"Our MR protocol can be performed in less than 30 minutes," Pedrosa emphasized at the ISMRM meeting. "It's important to point out that these MR sequences are available on any of the current MR scanners. The bread-and-butter of our protocol is the three-plane T2-weighted SSFSE (single-shot fast spin-echo) sequence." Other sequences used were transverse time-of-flight T2*-weighted gradient-echo imaging and transverse T2-weighted in-phase and opposed-phase imaging.

In group A, 12 patients had acute appendicitis and MR was positive in all cases, according to the results. Ultrasound was positive for appendicitis in three of the 12 cases. The normal appendix was visualized on MRI in 89% of the cases. The MR study was inconclusive in six patients with the majority (three patients) deemed as having a borderline enlarged appendix. For those without appendicitis, MR correctly identified the alternative diagnosis in six patients.

One patient out of two with false-positive MR exams underwent surgery. Three other patients from group A underwent negative laparotomies. The AAR was 73%, the NLR was 3.2%, and the PR was 17%.

In group B, seven patients had acute appendicitis and ultrasound was positive in two cases. There were also three true-negative cases on CT. The AAR was 54%, the NLR was 16%, and the PR was 14%.

The reduction in the NLR rate was significant and achieved "mainly through a dramatic improvement in the visualization of the normal appendix (on) MRI," Pedrosa noted. "The point of this (study) is not to show the sensitivity of (MRI and ultrasound), but the negative predictive value of both tests. When one rules out appendicitis with ultrasound, it's based on the lack of positive results. It's really an inconclusive result because the surgeon wants to know 'Do you see a normal appendix, yes or no?' The MRI, by showing a normal appendix, rules out the diagnosis of appendicitis."

An ISMRM audience member asked Pedrosa where the ultrasound exam fell in their overall imaging protocol for these patients. "We still like to do ultrasound first because ultrasound can provide a very fast diagnosis in certain cases," Pedrosa sated. "We (also) like to look at the ovaries and the kidneys, and (ultrasound) can assess those organs very fast."

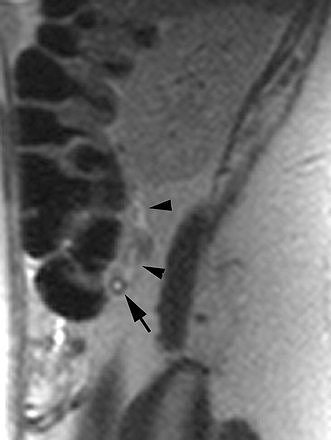

|

| Mild acute appendicitis in a 27-year-old pregnant woman (gestational age, 13 weeks). Above, transverse and, below, sagittal T2-weighted half-Fourier single-shot fast SE images (1076/60, 4-mm-thick sections, 192 x 256 matrix, 130° flip angle, 62-kHz bandwidth, 35-cm FOV) show an enlarged fluid-filled appendix measuring 7 mm in diameter (arrows). Note the increased signal intensity in the mesoappendix, a finding that is consistent with inflammatory changes (arrowheads). The MR images were interpreted as positive for acute appendicitis. Mild acute appendicitis was confirmed at surgery and pathologic examination. |

|

| Figures 2a,b. Pedrosa I, Levine D, Eyvazzadeh AD, et al. "MR imaging evaluation of acute appendicitis in pregnancy." Radiology 2006; 238:891-899. |

"If the clinical suspicion is very high for appendicitis, we don't wait for the ultrasound results. We start the oral prep for the MRI. In the meantime, we get the ultrasound results and the MR follows," he added.

In a follow-up e-mail interview with AuntMinnie.com, Pedrosa emphasized that sonography and MR are complementary, not competing exams, for assessing the appendix of pregnant women.

MRI without ultrasound "could be done if we had a patient with very high clinical suspicion for appendicitis," he explained. "However, in clinical practice, frequently this determination is not possible. The clinical presentation in most patients is not specific and one needs to rule out other pathologies than can masquerade as acute appendicitis. The ultrasound examination is a complementary test to MR that helps to evaluate some of these pathologies."

Pedrosa said the group's next phase of research will focus on an expanded patient population, as well as the finances of MRI in this setting. "The next step will be to perform a cost analysis on the use of MR in the diagnostic algorithm of pregnant patients with suspected acute appendicitis. Also, I expect that with more data (i.e., more patients) we will be able to define in what scenarios ultrasound is necessary versus those where we can go directly for MR," he said.

MRI tips

In an education exhibit in RadioGraphics, Pedrosa and colleagues offered some suggestions for making the most of MR in pregnant patients:

In addition to placing the patient in a supine position, they used a body phase-array coil.

SSFSE imaging overrides any degrading that may occur in these patients with limited breath-hold capability.

A fluid-filled appendix with a diameter of more than 7 mm on SSFSE should be seen as acute appendicitis. An appendiceal diameter of 6-7 mm without luminal air or oral contrast is indeterminate.

Other gastrointestinal tract disorders to watch for are complications from Crohn's disease and bowel wall pneumatosis. The latter can be difficult to detect on MR pulse sequences because of a lack of signal from air, they warned.

Obstetric and gynecological disorders that can manifest as abdominal pain include hemorrhagic cysts, pelvic endometriosis, ovarian torsion, benign and malignant ovarian masses, ectopic pregnancy, tubal hematoma, uterine fibroids, and urinary tract disorders.

Finally, the chart below lists some of the elements of the MRI protocol used:

|

|||

| Pulse sequences* | |||

| Parameters | Coronal SSFSE | Axial 2D FS SSFSE | 2D TOF |

|

|||

| Echo time (msec) | 60 | 60 | 100 |

| Flip angle (degrees) | 130-155 | 130-155 | 45 |

| Section thickness (mm) | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Gap (mm) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Field-of-view (mm) | 350 | 350 | 350 |

| Bandwidth (kHz)** | 62.5 | 62.5 | 31.25 |

| Breath-hold | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

|||

| *FS = fat-saturated, TOF = time of flight **62.5 kHz = 488 Hz/pixel, 31.25 kHz = 244 Hz/pixel |

|||

| Adapted from table 2, Pedrosa I, Zeikus EA, Levine D, et al. "MR Imaging of Acute Right Lower Quadrant Pain in Pregnant and Nonpregnant Patients." Radiographics 2007; 27:721-753. | |||

In a commentary on this education exhibit, Dr. Douglas Katz and colleagues predicted that MR will play a "somewhat larger role in the evaluation of patients with acute abdominal and pelvic pain in general." Some of the issues that still need to be resolved with MRI are improved availability after-hours and improved sequences, they added (RadioGraphics, May-June 2007, Vol. 27:3, pp. 743-753).

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 3, 2007

Related Reading

Routine use of diagnostic CT not advised for suspected appendicitis, May 24, 2007

MDCT of pregnant patient, August 4, 2006

MRI accurately rules out appendicitis in pregnant patients, March 2, 2006

Copyright © 2007 AuntMinnie.com