The use of functional MRI (fMRI) as a research tool has exploded as neuroscientists employ it to plumb the depths of the human psyche, measuring how our brains respond to advertising or even whether we're telling the truth. But what happens when incidental findings pop up on fMRI brain scans of healthy research participants?

Researchers at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver believe they've discovered a way to ethically and cost-effectively manage incidental findings in MR brain imaging of participants in research studies. Their technique relies on selective screening of individuals based on gender, age, and family history, according to a study in the July issue of Value in Health (published online June 17).

They found that it is more cost-effective to perform a full radiological exam before enrolling women with a family history of intracranial aneurysm in a brain imaging study. Men with no such family history have a lower risk of developing aneurysm, so the cost of a full neurologic scan prior to enrollment is not justified.

The researchers believe the study is the first economic analysis of current practices for managing incidental findings.

Disclosure debate

In MR brain research, previous studies have found that between 2% and 8% of incidental findings require clinical follow-up, with mostly a low -- but occasionally a high -- degree of urgency, according to the authors.

The issue of how to address the discovery of these anomalies has been part of an ongoing debate. "Strategies vary widely across laboratories and institutions," the authors wrote, "with options ranging from inaction (i.e., images are not screened for anomalies) to full clinical-grade imaging of all participants before their enrollment in a study."

In weighing the subject of incidental findings, study co-author Judy Illes, PhD, professor of neurology and director of UBC's National Core for Neuroethics, said the issues include the significance of the incidental finding in the brain. Is it clinically significant, or is it a benign anomaly that would never manifest if it had remained unnoticed?

"No. 2, whether or not it is significant, at the moment an anomaly is communicated to a human participant, one thing that is provoked is psychological anxiety," she added. "If a subject decides to pursue medical care, then the question is: Who pays for it? Whose responsibility is it?"

When there is an incidental finding, the participant will likely undergo clinical testing to evaluate the anomaly, potentially triggering a cascade of medical interventions and follow-ups. There also are potential costs to the individual, depending on his or her health insurance coverage, as well as time and degree of intervention.

"As always, the benefits are weighed against the costs, and then one has to make an assessment of that," Illes said.

Intracranial aneurysms

Intracranial, or vascular, aneurysms were chosen for study partly because, if left untreated, they can rupture and cause subarachnoid hemorrhage. As the study noted, treatment is available for the aneurysms, which also makes them "a relevant first target to rigorously evaluate the merit of different screening approaches to research fMRI studies."

"We know that of the incidental findings in the brain, the vast majority are of vascular origin and aneurysms are potentially fatal," Illes added. "We had to pick one model that was trackable, measurable, and for which some prior data existed, in terms of intervention."

The study explored four strategies for handling intracranial aneurysms in MR brain imaging with participants 18 years and older who said they were in good health. The four options were:

- Research scans were not routinely reviewed and no diagnostic or therapeutic workup was performed on any participant.

- Research scans were reviewed by a researcher, often a graduate student or postdoctoral fellow with no formal clinical training in radiology, and were referred to an MR-trained radiologist for evaluation if a brain anomaly was detected. If the finding was confirmed to be suspicious by the specialist, the participant was referred for a full diagnostic workup.

- Research scans were referred directly to an MR radiologist for formal review, and subjects with suspicious findings were sent for a full diagnostic workup.

- Prior to study enrollment, all research participants underwent a full workup including clinical-grade MR angiography.

Economic evaluation

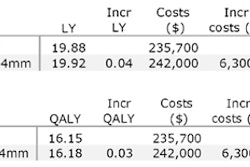

The study also calculated a cost-effective strategy for each group, with quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and willingness to pay. The researchers used the most common value for willingness to pay, according to recent research, of $50,000 per quality-adjusted life year. Given recent increases in QALY estimates, the study included an additional willingness-to-pay analysis of $100,000 per QALY.

The economic analysis found that costs ranged from $225.90 for no scans and no workup to $268 for scans done by a researcher or nonspecialist and a referral for workup, if an anomaly was found. When a scan was referred directly to a radiologist and then diagnostic workup, the cost increased to $404.20. In cases of a full workup prior to enrollment in a study, the cost was estimated at $1,004.

The researchers also devised a customized plan, which would have the highest net monetary benefit within each subgroup.

Compared to the first strategy of no scans or workup, a customized plan based on willingness to pay and $50,000/QALY resulted in a $90.40 increase in societal costs during the lifetime of subjects. By adopting the customized plan, society would pay $12,503 for obtaining one additional QALY compared to the strategy of not screening research subjects.

Based on $100,000/QALY, the customized plan, compared to the first strategy, resulted in a $354.70 increase in societal costs during the lifetime of subjects, with society paying $32,767 for one additional QALY compared to the strategy of no screening.

The study also found differences in cost-effectiveness among the subjects:

- A review of scans for incidental findings by a nonspecialist (strategy 2) is not cost-effective for any of the subgroups.

- In men with no family history of intracranial aneurysm, no review of scans is cost-effective.

- Clinical-grade MRI examinations, including MR angiography (strategy 4), for women with a positive family history before enrollment in a study are cost-effective.

It is difficult to extrapolate the group's results to other fMRI research studies, Illes said. "We are very cautious about that," she noted. "Those next studies have to be done. When we have more models, then we will be able to generalize perhaps to other cases we haven't tested. It is difficult to extrapolate from just one [study]."

She added it is "vital" to continue research in this area. If funding is available, she and her colleagues plan to follow that path.

"The challenges introduced by incidental findings are increasingly complex. Structural anomalies are only the beginning," Illes said. "We are now moving into combined technologies that include both imaging and genetic data, functional data, and we will have to pay very careful attention to our approaches to these challenges and our strategies for the maximum benefit of research, clinical care, and concern for public trust."

By Wayne Forrest

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 6, 2010

Related Reading

Incidental findings are common on brain MRI: meta-analysis, August 26, 2009

Incidental findings on brain MRI common as technology advances, November 1, 2007

Copyright © 2010 AuntMinnie.com