If a patient with an implanted cardiac device is referred for an MRI scan, can you scan him or her safely? Yes, even if the device is not one of the newer MRI-conditional devices, say cardiologists from Johns Hopkins University in a study published October 4 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

MR imaging of patients with cardiac devices has been generating growing interest since February, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared the first pacemaker that is conditional for use in an MRI environment (Revo MRI SureScan, Medtronic).

But what about patients who have older devices? As a general rule, they are considered a contraindication for MRI scans by both the FDA and device manufacturers. But Johns Hopkins researchers have been scanning these patients for years by carefully screening the devices and in many cases reprogramming them to operate more safely in an MRI environment.

Along the way, they've experienced only three cases (1.5%) in which a device reverted to its backup or default programming mode, with no long-term adverse effects (Ann Intern Med, October 4, 2011, Vol. 155:7, pp. 415-424).

First scans

Johns Hopkins scanned its first patient with these guidelines back in 2003, and the use of the protocol has expanded exponentially ever since. To date, more than 700 patients with implanted cardiac devices have safely undergone MRI exams at the university.

"It has become the standard of care in our hospital," said lead study author Dr. Saman Nazarian, a cardiac electrophysiologist and an assistant professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in an interview with AuntMinnie.com. "There are just so many patients with pacemakers and defibrillators. These are patients that are sick, have medical morbidities, and are at the hospital often, needing an MRI for one reason or another."

The protocols have worked so well because of "the strong collaboration between cardiology and radiology," Nazarian added.

The prospective study followed 438 people with implanted cardiac devices, who received a total of 555 MRI scans. The majority of the exams (94%) were conducted at Johns Hopkins and the others were performed at Rambam Medical Center in Haifa, Israel. There were no differences between the study centers in terms of patient age or sex, device models, or device indications.

Of the 237 patients with pacemakers, 184 (78%) received the device for symptomatic bradycardia and 53 (22%) for complete heart block. There were 201 patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), of whom 191 (95%) received the device for ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy, nine (4%) for right ventricular dysplasia, and one (0.5%) for irregular electrical activity in the heart.

The MRI safety process at Johns Hopkins begins by knowing which pacemakers and defibrillators are safer than others, based on the device's pulse generator, battery, and internal computer circuitry.

Defibrillator pulse generators manufactured after 2000 and pacemaker pulse generators made after 1998 tended to do much better when the researchers reviewed which devices did not function well after MRI exams.

"Just by scanning patients' pacemakers and defibrillators out of the body initially, we could determine which devices were safe to [image] and which ones we did not want to scan," Nazarian said.

Heated wires

The researchers also found alterations in the patients' pacemakers and defibrillators that would make them unsafe for MRI. For example, there are cases where a nonfunctioning lead -- the wire that connects the pulse generator to the heart -- is intentionally left in a patient because its removal is more risky.

Once a wire has been implanted for a few weeks, it adheres to the wall of the heart and the proximal portion is sewn to the muscle where it enters the vessel. When the lead is not connected to the generator, it can still be fueled by the strength of the MRI magnet and heat up.

"When it is left in as a nonfunctioning lead that is not connected to a generator, doing an MRI scan can be less safe, because [the lead] can heat up more," Nazarian said, adding that having a nonfunctioning lead is not uncommon for many patients.

Additionally, there are wires placed on the vessels inside and outside the heart. These types of wires also tend to heat more during an MRI scan.

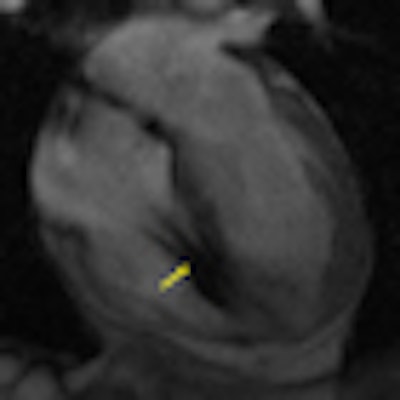

|

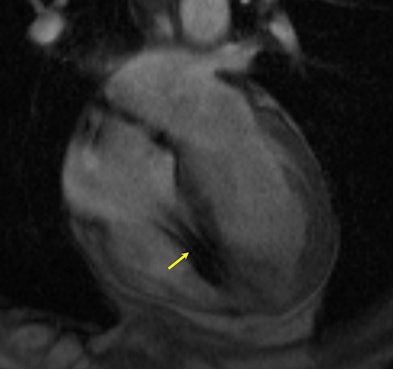

| MR image shows a heart with a defibrillator lead in the right ventricle (yellow arrow). Image courtesy of Dr. Saman Nazarian. |

While an x-ray can detect whether or not a nonfunctioning lead is connected to the generator and whether there is an unconnected wire on the inside or outside of the heart, Johns Hopkins does not need to take an x-ray of a patient, Nazarian said. "We typically obtain all the records so we can go through them and see exactly what kind of device the patient has," he said.

Pacing functions

Another major consideration of the university's protocol is that some patients are completely dependent on the pacing function of their device. If the patient has a pacemaker, he or she can still receive an MRI scan. However, if the patient has an implantable defibrillator and is dependent on the pacing function, "that is a situation where we do not scan the patient," Nazarian said.

Three patients (1.5%) experienced a power-on reset event during their MRI scan, which happens when the electromagnetic energy emitted from the scanner causes the device to revert to default settings.

"It is a small number, but it is something we need to be aware of," Nazarian said. "It is not a permanent problem with the device. As long as nothing happens during the scan, you can program the device afterward and it will function just as well as it did before."

None of the three cases had device dysfunction during the long-term follow-up of between 15 and 66 weeks. One of the patients completed four repeated MRI examinations during the study without any problems.

"A good number of patients have this condition, [where they do not have an intrinsic heartbeat]," Nazarian said. "When we see a patient like this who needs an MRI, we change the programming of the pacemaker before we do the MRI and program it in such a way that [the pacemaker] ignores any electromagnetic interference in any noise that it senses."

If the pacemaker senses the noise from the scanner, the device may think there is enough of a heartbeat and it does not need to pace. That would be a dangerous situation for the patient, Nazarian added.

If physicians set the device to a mode called asynchronous pacing for the scan, the pacemaker ignores electromagnetic interference and the patient can undergo the MRI safely.

For situations when a power-on reset can be dangerous if the patient is not monitored, the Johns Hopkins' protocol includes adding a pulse oximeter on the patient's finger or ear lobe to monitor pulse oxygenation, along with the required electrocardiogram (ECG) monitor.

Pulse oximetry

"If you are doing an MRI and you only have ECG monitoring, that could have a lot of artifact on it during an MRI," Nazarian said. "What we found works best is to have both ECG monitoring and pulse oximetry. That is very reliable, because it does not have any noise on it during the MRI scan."

He added that if Johns Hopkins physicians find any disruption to the pacing function, they stop the scan immediately. When the scan stops, the noise goes away, and even if the pacemaker is in a backup inhibited mode, it will start pacing normally again.

The most referrals for MRI scans of patients with devices have come from the university's neurology and neurosurgery departments to view brain masses or stroke. "The other large area for referral is for malignancies -- in general, anywhere in the body -- because it is a soft-tissue mass," Nazarian said. "In terms of defining soft-tissue borders, MRI seems to be far superior to CT."

While Johns Hopkins' guidelines have worked well since their inception, Nazarian and his colleagues plan to continue expanding their database and research because the imaging procedure "is not routine care, and it is important to keep looking for possible situations where it is not safe."

Other healthcare institutions have similar guidelines in place to ensure safe MRI scans with implanted cardiac devices. Johns Hopkins has also helped other hospitals and facilities implement the institution's protocols for their patients.