VIENNA - While in most cases it's not life-threatening, endometriosis has a substantial impact upon women's quality of life and may sometimes be the cause of infertility. Radiologists involved in diagnostic workup for suspected endometriosis are strongly urged to make a checklist of areas needing investigation when presented with such cases.

This plea came from speaker Prof. Karen Kinkel, head of female imaging at the Institute of Radiology, Clinique des Grangettes, Geneva, Switzerland, in her talk about diagnosing endometriosis through imaging, which formed part of Sunday's categorical course on the female pelvis.

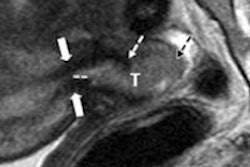

"You should always check the area behind the cervix, in between the start of both uterosacral ligaments," she told delegates. She illustrated her point with an asymmetrical image in the torus uteri, the ligaments presenting as small and normal on the right side but thickened on the left side, which was abnormal.

Prof. Karen Kinkel, head of female imaging at the Institute of Radiology, Clinique des Grangettes, Geneva, Switzerland. All images provided by ESR.

Prof. Karen Kinkel, head of female imaging at the Institute of Radiology, Clinique des Grangettes, Geneva, Switzerland. All images provided by ESR.

Endometriosis can go deeper, low down through the posterior vaginal cuff coming from the retrocervical area to the anterior rectal wall. Anterior deep endometriosis should also be sought in the space between the bladder and the uterus, with imaging showing bladder wall thickening, if present.

"Those type of lesions cause chronic pelvic pain. In fact, the type of pain can give you a hint about the area the endometriosis might be," Kinkel said in the session moderated by Prof. Veronika Gazhonova, chair of the radiology department, United Hospital and Polyclinic, and professor of radiology at the President Medical Centre, Moscow.

Linking symptom to location, Kinkel cited dysmenorrhea as a symptom of adhesions in Douglas' pouch. Dyspareunia, on the other hand, could be caused by endometriosis in the uterosacral ligaments and torus uterinus rather than adhesions in the vagina. Painful defecation during menstruation could also stem from endometriosis in the vagina or Douglas' pouch, while bowel adhesions often caused noncyclic pain. Lower urinary tract symptoms clearly pointed to potential endometriosis in the bladder, Kinkel concluded.

Ultrasound is the first line tool for diagnosing endometrioma (endometriosis of the ovaries) and bladder endometriosis. MRI, however, had the highest sensitivity to identify all lesion locations on the checklist, and the status of lesions should be checked in all three orientations at T2.

"Radiologists should use rectal contrast if the patient complains about painful defecation during menses, but remember that lesions are often dark at T2 and not seen in fat-saturated T1 except for in the abdominal wall," she said.

Radiologists play a vital role in distinguishing atypical endometrioma from ovarian cancer or cystic teratoma, which require vastly different management. Endometrioma will show a diffuse low-level internal echo and hyperechoic foci in ultrasound while cystic teratoma is quite different, according to Kinkel.

"Cystic teratoma have layered lines and dots, fat fluid levels, and isolated bright foci with acoustic shadowing, and are easy to distinguish from endometrioma," she said.

Dr. Evis Sala, lecturer in radiology at Cambridge University and radiologist at Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge.

Dr. Evis Sala, lecturer in radiology at Cambridge University and radiologist at Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge.

Ruling out differential diagnoses of ovarian cancer could be achieved through color Doppler, which in endometrioma would show negative for vessels. Conversely, complex ovarian cysts with a solid portion could be deemed highly suspicious for cancer if vessels could be visualized inside the mass with color Doppler imaging.

Speaking about the acute female pelvis, Dr. Evis Sala, lecturer in radiology at Cambridge University and radiologist at Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, reviewed the lacelike or fishnet appearance of the hemorrhagic cyst on ultrasound, and the grayscale ultrasound features in ovarian torsion that include the "string of pearls" sign, free pelvic fluid, and an extraovarian echogenic, targetlike mass, or twisted vascular pedicle.

"Ultrasound is generally preferred as a first step as it is more sensitive to vascular flow within the ovary. Grayscale findings of enlarged ovary with multiple peripherally placed small follicles are diagnostic," she elaborated. "Difficulty arises with masses and compressed ovary, or with persistent flow. To avoid missing torsion, maintain a high index of suspicion and be willing to accept some negative laparoscopies."

She also outlined the advantages of MRI in the pregnant patient with acute or subacute symptoms. MRI is safe in the second and third trimesters and is highly accurate for characterizing indeterminate adnexal lesions found on ultrasound, she said.

Completing the session, Dr. Thomas Kroencke, radiologist at the Charité Hospital, Berlin, provided an update on image-guided therapy for leiomyomas, the most common benign uterine tumors that affect women between the ages of 40 and 60. Rarely life-threatening, symptoms can range from severe pain to obstipation, urinary frequency, and infertility. Although there were uterus-sparing options available, hysterectomy remained the most frequent treatment, Kroencke told delegates.

His talk covered the appearance of leiomyomas on both ultrasound and MRI and moved on to innovative treatments currently in clinical practice such as MR-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS), uterine-sparing resection, and uterine fibroid embolization (UAE).

"MRI plays a key role for assessment of extent of disease and treatment stratification," said Kroencke, concluding the session. "The spectrum of therapeutic options for symptomatic leiomyomas has broadened, and now individualized therapy with MRgFUS and UAE is establishing itself as alternatives to surgery."

Originally published in ECR Today March 5, 2012.

Copyright © 2012 European Society of Radiology