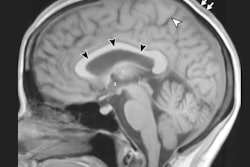

Researchers using MRI have discovered optical abnormalities in the eyes and brains of 27 astronauts who spent prolonged time in space. The abnormalities are similar to defects found in cases of intracranial hypertension, according to a study published online March 13 in Radiology.

Intracranial hypertension is a potentially serious condition in which pressure builds within the skull. Researchers from the University of Texas (UT) Medical School at Houston believe the physiologic changes occurring during exposure to microgravity and space may help determine the causes behind intracranial hypertension under normal gravitational circumstances.

The 27 astronauts in the study had a mean age of 48 years and were exposed to microgravity or zero gravity for an average of 108 days while on space shuttle missions and/or serving on the International Space Station. On their return to Earth, all 27 astronauts received exams on a 3-tesla MRI scanner (Intera, Philips Healthcare) with thin-section, 3D, axial T2-weighted orbital and conventional brain sequences. Eight of the 27 astronauts underwent a second MRI after a second space mission that lasted an average of 39 days.

Lead study author Dr. Larry Kramer, professor of diagnostic and interventional imaging at UT, noted that because all astronauts were exposed to microgravity, no control data were available for comparison.

However, the MRI findings uncovered various combinations of abnormalities following both short- and long-term cumulative exposure to microgravity also seen with idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

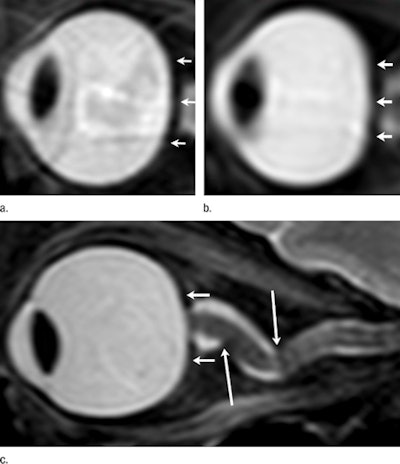

Nine (33%) of the 27 astronauts with more than 30 days of cumulative lifetime exposure to microgravity experienced more cerebral spinal fluid space surrounding their optic nerve, while six astronauts (22%) with more than 30 days in space exhibited flattening of the rear of their eyeball. Four astronauts (15%) in the same group showed bulging of the optic nerve, while three astronauts (11%) displayed changes in the pituitary gland and its connection to the brain.

|

| Sagittal oblique T2-weighted MR images show a left eye (a) before long-term exposure to microgravity. Convexity of posterior globe is noted (arrows). Another left eye image (b) shows long-term exposure to microgravity, with the loss of convexity of the posterior scleral margin (arrows). The right eye (c) of a different astronaut notes two abruptly angulated foci (long arrows) in optic nerve sheath and posterior globe flattening (short arrows). Images courtesy of Radiology. |

The same types of abnormalities are seen in cases of intracranial hypertension where no cause can be found for increased pressure around the brain. The pressure causes swelling between the optic nerve and the eyeball and eventually can result in impaired vision.

Kramer and colleagues cited several limitations of their retrospective analysis, including the lack of a control group, "a significant time delay" to postflight imaging in most astronauts, and the absence of concurrent cerebrospinal fluid or intraocular pressure measurements.

"Visual acuity degradation in astronauts exposed to microgravity is a newly recognized phenomenon," the authors wrote. "Although the exact mechanism is yet to be fully elucidated, the constellation of MR findings alone suggests that intracranial hypertension is an important component, drawing similarities to [intracranial hypertension] and substantiated by direct [cerebrospinal fluid] pressure measurements in a small subset of astronauts after flight."