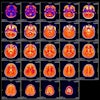

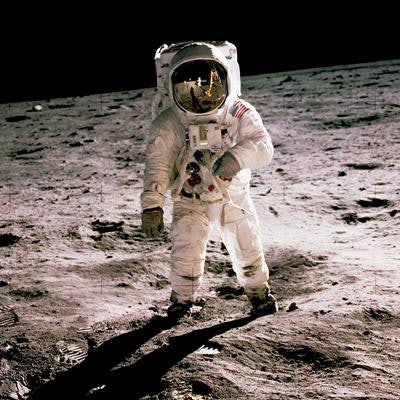

Astronauts should take heed of how time in space could affect the brain. Diffusion-tensor MR images (DTI-MRI) have revealed brain changes in astronauts based on how long they were in space, according to a study published online January 23 in JAMA Neurology.

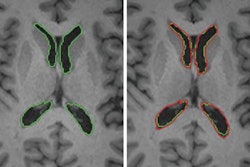

The researchers found fluctuations in extracellular fluid and white-matter volume, which they believe may reflect fluid shifts and an upward movement of the brain, both of which occur in microgravity. They also observed greater alterations in white-matter volume than are seen in the normal aging process.

"Some of these brain changes were associated with the number of previous spaceflight missions, mission duration, and preflight to postflight balance declines," wrote the group led by Jessica K. Lee, PhD, from the College of Health and Human Performance at the University of Florida.

Astronauts must maintain peak mental and physical function, and the brain is, of course, one critical component. However, one recent study found a loss of gray-matter volume in the brain soon after astronauts touched down and prolonged changes in the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid seven months later.

The integrity of white matter is important as well, given its association with cognitive ability and motor skills. It also "may provide insight into the neural mechanisms underlying the declines in balance, locomotion, and manual control that astronauts experience as a result of spaceflight," Lee and colleagues noted.

To further investigate any brain changes that occur with space travel, the researchers analyzed 15 astronauts (median age, 47.2 ± 1.5 years). Six men and one woman were on space station assignments of 30 days or less, while six men and two women were on board for 200 days or less. All 15 travelers underwent DTI scans on a 3-tesla system (Magnetom Verio, Siemens Healthineers) prior to their flight and again when they returned to Earth.

In comparing the pre- and postflight results, the researchers found a widespread increase in free-water volume in the frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes, along with a decrease in free-water volume in the posterior aspect of the vertex. All changes were statistically significant and ranged from approximately 2.5% to 4.0% across the brain regions. MRI also showed significant white-matter changes, ranging from approximately 0.75% to 1.25%, in the right superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculi, the corticospinal tract, and the cerebellar peduncles.

The amount of time astronauts spent in space and the number of missions were also factors in the degree of free-water changes. Astronauts who flew fewer missions experienced greater increases in free water in the anterior cingulate cortex; conversely, those who flew more often showed free-water decreases in the same region.

"This [finding] implies that the number of gravitational transitions experienced has an important effect on the free-water compartment. ... It is possible that repeated adaptation to multiple gravitational transitions may affect the gross morphology of the brain and its plasticity," Lee and colleagues wrote.

"Ongoing, prospective studies will help to elucidate recovery time course and performance consequences," they concluded. "Future work should also address whether and how these brain changes are linked to spaceflight neuro-ocular syndrome."