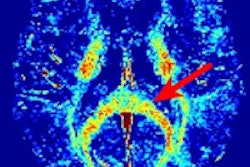

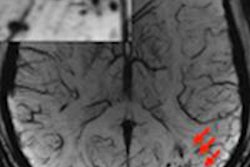

Susceptibility-weighted MRI (SWI-MRI) can identify microstructural changes in the brains of male and female college-level ice hockey players that may be due to concussions.

Results of the study were published online February 4 in the Journal of Neurosurgery. The researchers believe the study is the first to use SWI-MRI to detect signs of mild traumatic brain injury (by identifying smaller microbleeds than previously detected). They also believe it's the first to use the technique to detect changes in the brain prospectively over a sports season in athletes of both sexes.

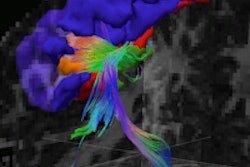

The high-resolution, 3D technique is particularly sensitive to the presence of blood and blood-breakdown products. It is designed to detect small hemorrhages that appear hypointense on T2-weighted MR images and are often the result of traumatic brain injuries.

During the hockey season, out of 25 men and 20 women, five male and six female athletes sustained concussions that were diagnosed independently by medical specialists. These athletes underwent additional SWI-MRI at 72 hours, two weeks, and two months after their injuries, along with serial clinical and neuropsychological evaluations.

At all time points, SWI identified small clusters of hypointensity in all athletes. To compare the extent of these hypointense regions within and between individual athletes and groups of athletes, the researchers calculated a hypointensity burden (HIB) metric for each athlete at each SWI time point.

Among the nonconcussed athletes, there was no significant change in HIB overall during the season. However, the researchers did notice significant differences in HIB according to gender, with male athletes having significantly higher mean HIB values than female athletes at both the beginning and end of the season.

Among the concussed athletes, there was a statistically significant difference between the HIB value at the beginning of the season and the value two weeks after concussive injury in male athletes; there was a similar though not significant difference during the same period in female athletes.

"Data acquired using this method could be used for the monitoring of players throughout their careers and could lead to improved diagnoses and return-to-play guidelines," wrote lead author Karl Helmer, PhD, and colleagues from Massachusetts General Hospital and several other institutions.

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)