Using MRI, Canadian researchers have created for the first time in vivo images of myelin damage in the human brain after a sports-related mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) -- in this case in Canadian hockey players.

The University of British Columbia study found a 6% (± 1.2%) decrease in myelin, the insulating sheath that protects the nerve fibers in the brain, based on MRI scans acquired at the start of the season and two weeks after injury in 11 concussed hockey players.

"Our data shows that after two weeks, there is still significant change in myelin," said co-author Dr. Alexander Rauscher, assistant professor and Canada Research Chair in developmental neuroimaging at the university. "That is longer than what is seen in neuropsychological tests done on people with concussions. So, there may be some residual change in the brain that is not visible or detectable by cognitive tests."

There is, however, some good news for concussed athletes who play contact sports. The myelin recovers within two months of the injury.

Myelin's function

Myelin is critical to brain function, and any disruption can lead to a disability.

"If [myelin] gets damaged, it causes problems," Rauscher told AuntMinnie.com. "The most common disease associated with myelin damage is multiple sclerosis."

Dr. Alexander Rauscher from the University of British Columbia.

Dr. Alexander Rauscher from the University of British Columbia.The researchers noted that much of the data on the adverse effects of mild TBI come from postmortem studies and animal models.

"Specifically, the dynamic effects of acute mild TBI on myelin in the human brain represent a major gap in our understanding of these injuries," they wrote (PLOS One, February 25, 2016).

The current study uses the same cohort of athletes from 2015 research in which Rauscher and colleagues found that playing contact sports could lead to subtle subclinical changes in brain volume.

"We scanned these people before they had the concussion," he explained. "A prospective neuro study in humans can only be done when you have people with high risk for injury. That was a key aspect of the study -- to work with the high-risk group so we could have pre- and postinjury data and compare them."

MRI scans were performed on a total of 45 hockey players between the ages of 18 and 36 years, both before the season and at the end of the season.

The researchers used a 3-tesla scanner (Achieva, Philips Healthcare) equipped with dual gradients and an eight-channel standard sensitivity encoding (SENSE) head coil. A 32-echo, T2-weighted scan (14 minutes, 22 seconds) was performed for myelin assessment.

During the season, 11 players (five men and six women) experienced concussions. They received follow-up MRI scans three days, two weeks, and two months after their injuries.

The researchers analyzed myelin water fraction changes and compared concussed athletes' baseline MR images to subsequent MRI scans.

Concussion effects

At the start of the study, myelin water maps showed no significant differences in myelin water fraction between baseline MRI scans of nonconcussed athletes and players who later suffered mild traumatic brain injuries.

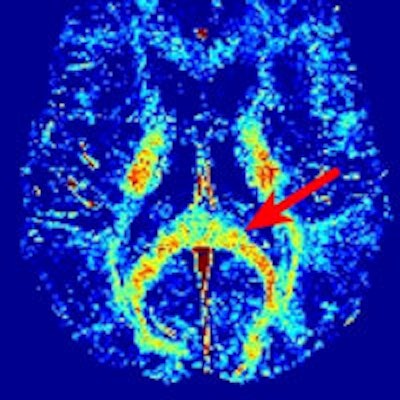

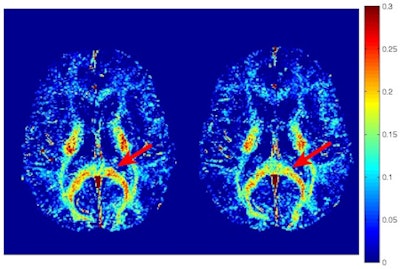

As one would expect, there also were no significant differences between preseason and postseasons scans of players who had no head injuries. Among the concussed athletes, the myelin water maps showed clusters of voxels with significantly reduced myelin water fraction -- a reduction of 6% (± 1.2%) -- two weeks after the injury, compared with baseline results.

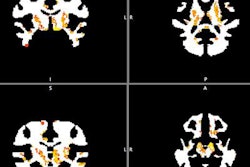

Changes were most evident in the splenium of the corpus callosum, right posterior thalamic radiation, left superior corona radiata, left superior longitudinal fasciculus, and left posterior limb of the internal capsule.

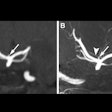

Myelin water fraction maps show a concussed athlete at baseline (left) and two weeks after the injury (right). A region of the corpus callosum had a visible reduction in myelin water fraction postinjury (red arrow). Image courtesy of PLOS One.

Myelin water fraction maps show a concussed athlete at baseline (left) and two weeks after the injury (right). A region of the corpus callosum had a visible reduction in myelin water fraction postinjury (red arrow). Image courtesy of PLOS One.Interestingly, the researchers discovered a decline in myelin water fraction 72 hours after the injury in these voxels, but the results did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.076). There were no significant myelin water fraction changes between the baseline scans and those two months after the injury.

"The exact time course of myelin alterations following sport-related concussion cannot be determined from this exploratory study," the authors wrote. "As the subjects were acutely concussed and enduring the worst phase of their symptoms, only eight of the 11 subjects were able to complete the 72-hour scan. It is possible that the reduced sample size at this time point may have obviated statistical significance from being achieved."

Recovery time

There are two key findings in the study. One is the strong inference that the "changes in myelin water fraction are indicative of true changes in myelination within the brain," the authors wrote.

Second, the lack of significant myelin water fraction changes two months after a concussion would suggest that the myelin has recovered during that time. How and why the myelin recovers remains "an open question," Rauscher said.

Even though myelin water fraction changes appear to become less severe after two weeks, it is likely in the best interest of athletes who play contact sports to delay their return to the playing field, he noted.

"The imaging data shows that change takes longer than normally seen. I don't think [the athletes' conditions] will change overnight to normal on day 15 after the injury," he said. "It is probably safe to assume there is still some residual [myelin] change after three weeks, even though we don't have a measurement at three weeks. The neuropsychologists and sports medicine people have a good idea on how to translate that into what should be done in ice hockey."

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)