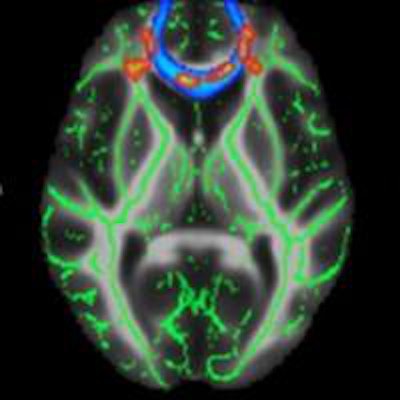

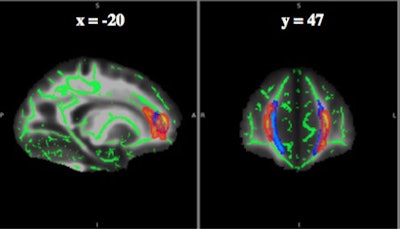

CHICAGO - Repetitive hits to the head and a history of concussions can affect different areas of the brain in former collegiate and professional football players, based on the player's position, according to a comparison of diffusion-tensor MR images (DTI-MRI) presented on Monday at RSNA 2015.

Researchers found lower fractional anisotropy values -- an indication of abnormal movement of water molecules in brain tissue -- in frontal white-matter tracts of nonspeed players, such as offensive and defensive linemen, compared with speed positions, such as quarterbacks, running backs, wide receivers, linebackers, and defensive backs. (Kickers were not included in the study.)

More specifically, fractional anisotropy values varied significantly in three clusters in the forceps minor and genu of the corpus callosum, based on the player's position.

"The forceps minor and genu of the corpus callosum cross over the two hemispheres of the brain and are closely connected to the frontal cortex, which is associated with cognition and higher-level functioning," explained study co-author Michael Clark, an MD-PhD candidate at the University of North Carolina (UNC) School of Medicine. "We believe that might be related to the types of head impacts that these players are exposed to, especially in the nonspeed positions."

Front-line experience

Lead study author Allen Champagne is a former defensive lineman at UNC. At the time of the study two years ago, he was an undergraduate at the university and made this research part of his honors thesis. Since then, Champagne has returned to the master's program at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, in Canada.

Lead author and former UNC football player Allen Champagne.

Lead author and former UNC football player Allen Champagne."Being a former defensive lineman on the college level, I am aware that there are risks in terms of concussions by being on the field," Champagne said during his RSNA presentation. "And I would like to know more about what is going on."

There has been much research in recent years on how concussions and repeated head trauma affect football players who are active at various levels of competition. A number of papers have explored whether these injuries may cause chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a progressive neurodegenerative disease in people with a history of repetitive brain trauma.

"If a player is hitting their head aggressively on every play, does that have a cumulative effect? And does that contribute to later-life cognitive decline?" Clark asked.

The study enrolled 32 former college football players with a mean age of 58.2 years (± 3.7 years) and 31 former professional football players with a mean age of 58.5 years (± 3.6 years), who were matched based on age, concussion history, and playing position.

The former college players who had one concussion or less and those who had three concussions or more played for a mean of approximately eight years, which includes participation before college. Former professional players with one concussion or less or three concussions or more were active for a mean of approximately 17.6 years.

Study co-author Michael Clark from UNC School of Medicine.

Study co-author Michael Clark from UNC School of Medicine.The researchers also tallied the number of "contact hours" based on the former athletes' practice and game time. Former college players with one concussion or less had a mean total of 1,062 contact hours, compared with a mean 1,332 contact hours for those with three concussions or more.

Interestingly, former pros with one concussion or less had more mean contact hours, at 3,284, than retired professional players with three or more concussions, at 3,041.

So, one study goal was to determine any ramifications of additional playing time in the National Football League (NFL) in regard to the number of concussions each subject reported.

"With nonspeed positions, they are experiencing an impact on every play with the person who is lined up 1 foot away, versus the speed positions, who take impacts at higher rates and have much more closing distance between them and the people they are impacting," Clark said.

All subjects were cognitively normal for their age, based on a series of neuropsychological tests. They were imaged on a 3-tesla MRI scanner (Trim Trio, Siemens Healthcare), which included T1-weighted and T2-weighted imaging, along with functional MRI as part of the single-scan protocol.

The players were also given an n-back cognitive test while in the scanner to measure brain activity through functional MRI. The n-back task evaluates subjects' working memory by asking them to recall a sequence of letters and numbers and press a button each time they see the image again.

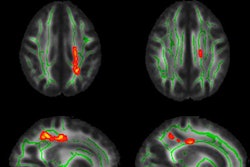

Upon analysis, diffusion-tensor imaging revealed consistently lower fractional anisotropy for nonspeed players with a history of three or more concussions, compared with players with one or no concussions, in the forceps minor and genu of the corpus callosum near the frontal cortex.

DTI measures the movement of water molecules in tissue and white-matter brain regions through fractional anisotropy to determine disruptions in flow. The lower the fractional anisotropy value, the more likely there is a microstructural abnormality.

"In all three clusters, we see consistent differences in nonspeed players with a high concussion history with lower fractional anisotropy, which has been known to degrade white matter," Champagne said.

The statistical heat map for the concussion-position interaction is shown in red-orange. The major clusters were within the frontal white matter, specifically within the forceps minor (blue). This result suggests there may be a modifying effect of subconcussive impact exposure on damage to white-matter structures caused by recurrent concussions. This modifying effect appears most prominently in the frontal white-matter structures. The implications of such white-matter structural changes on late-life cognitive function are unknown. Images courtesy of Allen Champagne and Michael Clark.

The statistical heat map for the concussion-position interaction is shown in red-orange. The major clusters were within the frontal white matter, specifically within the forceps minor (blue). This result suggests there may be a modifying effect of subconcussive impact exposure on damage to white-matter structures caused by recurrent concussions. This modifying effect appears most prominently in the frontal white-matter structures. The implications of such white-matter structural changes on late-life cognitive function are unknown. Images courtesy of Allen Champagne and Michael Clark."That led us to believe that it may be because of the impacts [nonspeed players] are receiving in the front of their helmets," Clark said. "They might not receive as many high-magnitude impacts, but they receive a lot of lower ones, which may have an effect."

The researchers did not find any main effects of football exposure, which would suggest that without concussive injuries, playing the additional years in the NFL did not account for any variances in fractional anisotropy or mean diffusivity.

Future research

The researchers are still analyzing the functional MRI data, but preliminary results suggest that regardless of concussion history or player position, the subjects appear cognitively normal, Clark said.

"On all of our pencil tests and cognition tests, they all performed within normal limits," he said. "When they did the task in the scanner, [both speed and nonspeed player groups] had the same accuracy. We can't say that either [group] had worse cognition, but what we are looking at with functional MRI is how much of their cognitive resources they need to recruit to complete this task."

One contributing factor to how much additional processing is needed to complete cognitive tasks is concussion history. "It seems that concussion history plays more of a role in this 'overrecruitment' of resources to respond to tasks than does exposure [to head impacts], but they both seem to have a role," Clark said

"Our findings are exciting, but they are preliminary and we do not want to make early conclusions," Champagne told attendees. "We do think that the nature of exposure and concussion history play a major role with regard to differences in white-matter integrity in football players, which is why we are currently working on an appropriate model to define the proper position variable."

The researchers are now working with imaging biostatisticians to develop that model, which would include a proper player variable to reflect the nature of head impacts based on position.

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)