CHICAGO - New MRI-based research suggests that changes in the brain linger after athletes appear to recover from the cognitive symptoms involved with a concussion, according to results presented in a press conference at this week's RSNA 2015 conference.

Blood flow appears reduced in multiple regions of the brain at eight days, compared with what was revealed by MRI scans at 24 hours, said Michael McCrea, PhD, a professor of neurosurgery and director of brain injury research at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

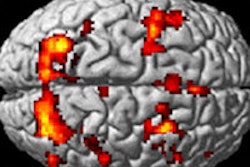

The researchers compared football players who had sports-related concussions with nonconcussed controls, using MRI with arterial spin labeling to measure blood flow in the brain. They obtained MRI scans of the concussed players within 24 hours of the injury, along with a follow-up MRI eight days after the injury.

About 30% to 35% of the players in the study had experienced a previous concussion, McCrea said.

Clinical assessments were made using the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 3 (SCAT3) and the Standardized Assessment of Concussion (SAC). At 24 hours after the injury, the concussed players showed significant impairment at clinical assessment, but they returned to baseline levels at eight days. Their MRI scans told a different story, however: The concussed players had a significant decrease in blood flow at eight days, compared with their 24-hour results. Meanwhile, the nonconcussed players had no change in cerebral blood flow between the two time points.

At the press conference, McCrea said his report was preliminary, so he was unable to state how long the reduced blood flow in the brain continues -- or whether it has a clinical impact. The present study will look at brain blood flow again at six months. Future studies, he suggested, may include MRI at more frequent intervals.

"The tail of physiologic recovery extends beyond the point of clinical recovery," McCrea explained. "It's not reduced to what are the signs and symptoms manifested by this extended tail of physiologic recovery. It really pertains more to the discussion about that person's readiness to return to activity, where they're certain to sustain additional head impacts."

McCrea said that players who experience concussions on the field may report that physical symptoms such as headache and dizziness resolve after about three days, and cognitive functioning may also improve to baseline within a few days.

As recently as 2008, about 20% of high school athletes rendered unconscious on the field returned to play that day, he noted. By 2012, it was general policy that no athlete who experienced such an episode should be allowed back on the field that day. By 2015, the time to resume play was extended to about 15 days.

"Those extra days not only provide the athlete adequate rest and clinical recovery, but it's also going to put them in a better place in terms of physiologic recovery," he said.

"The end-game here, from a translational perspective, is that decision-making around fitness to return to activity is dependent not only on what we observe to be their clinical recovery, but on their readiness from a physiologic standpoint to return to activities that may render them at risk for secondary injuries down the line," McCrea said.

"We are at a very early stage in understanding how the brain recovers from concussions and injuries in general," said press conference moderator Dr. Salomao Faintuch, clinical director of vascular and interventional radiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and assistant professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School. "Recovery time may be much slower, and we can't currently determine that based on clinical symptoms alone. We're looking forward to getting more data on how long it takes the brain to fully recover."