Structural MRI revealed brain scars in the form of white-matter T2-weighted hyperintensities in more than half of active duty military personnel who had blast-related predominantly mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) in a study published online December 15 in Radiology.

In what they believe is the largest study to use advanced neuroimaging in soldiers with TBI, researchers from Walter Reed National Military Medical Center found T2 hyperintensities in 52% of the patients with TBI. The results deviate from the accepted consensus that people with mild TBI have normal MRI results.

The presence of these brain scars in this predominantly young group is unusual and could represent traumatic brain injury; however, the researchers noted that it is difficult to definitively determine the source of the hyperintensities without a baseline MRI prior to the injury.

"It is difficult to know exactly what to make of this, but the fact is that [T2 hyperintensities] are there," said lead author Dr. Gerard Riedy, PhD, chief of neuroimaging at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence at Walter Reed. "If you have 20 T2 hyperintensities in a 20-year-old person who is otherwise healthy and the one indication is exposure to a blast, you have to wonder where they came from. They are clearly abnormal. The question is: What is the origin of them and what do they mean?"

Incidence of TBI

More than 300,000 service men and women were diagnosed with mild traumatic brain injury between 2000 and 2015, according to the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. White-matter T2-weighted hyperintensities are commonly caused by aging, diabetes, and hypertension.

"You have to have a fair amount of hyperintensities before you have any real clinical effects," Riedy told AuntMinnie.com. "You can have some mild cognitive impairment, but the brain has a fair amount of reserve. I think these things are just tiny 'hits' on the brain."

Because the military personnel are operating at such a high level of brain function, Riedy did not know if it were possible to measure a clinically relevant effect from these brain scars.

"We are reducing the brain's capacity, but the brain still has a lot of capacity and reserve," he said. T2 hyperintensities are "more a marker of what has happened with this person in the past. Then the question becomes: What does the future look like for this person?"

Imaging protocol

The study included 792 men with a mean age of 34 years (± 8.1 years) and 42 women with a mean age of 33 years (± 11.3 years). Among this group, 688 people (84%) had blast-related incidents, 561 (69%) had multiple blasts, and 212 (26%) had two or more blasts or injuries within one month (Radiology, December 15, 2015).

In all, 768 soldiers (92%) had mild TBI, 52 (6%) had moderate brain injury, and 14 (2%) had severe TBI. The researchers also scanned 42 healthy active-duty service members who had no history or diagnosis of traumatic brain injury, psychologic disorders, or vascular pathologic results to serve as a comparison group.

MRI scans were performed on a 3-tesla scanner (Discovery MR750, GE Healthcare) with a 32-channel head coil at two locations between August 2009 and August 2014. The structural MRI protocol included T1- and T2-weighted gradient-recalled echo (GRE) imaging, susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI), and T2 fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery (FLAIR) imaging after an injection of gadolinium contrast.

The 90-minute MRI scan also involved four functional MRI (fMRI) sequences, diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI), perfusion, and MR spectroscopy as part of the protocol.

Discovering hyperintensities

One or more white-matter T2-weighted hyperintensities were seen in 432 subjects (52%) with TBI, compared with 16 (38%) of the 42 healthy volunteers (p = 0.057), a difference that was not statistically significant.

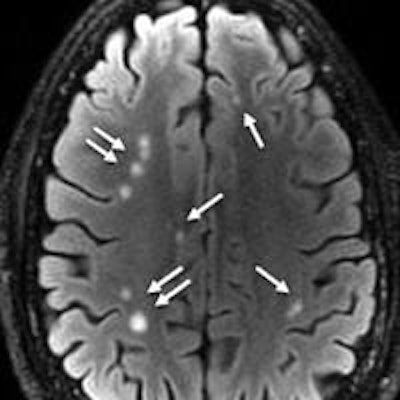

A 28-year-old man with blast-related TBI had multiple white-matter T2-weighted hyperintensities (arrows). Axial T2 FLAIR MRI discovered a total of 76 lesions on all sections. Image courtesy of Radiology.

A 28-year-old man with blast-related TBI had multiple white-matter T2-weighted hyperintensities (arrows). Axial T2 FLAIR MRI discovered a total of 76 lesions on all sections. Image courtesy of Radiology.

Microhemorrhage was seen in only 60 (7%) of the 834 subjects. Among the individuals with microhemorrhage, 35 (58%) had both T2-weighted hyperintensities and microhemorrhage at MRI.

"Quite honestly, we did not expect to see all that much with structural [MR] imaging," Riedy said. "It had been done for years and not really led to much in the way of results. We expected more advancement in research and certainly the diagnosis of TBI from DTI, functional MRI, spectroscopy, and other modalities."

Structural MRI also located pituitary abnormalities in 29% of the TBI subjects. Previous research has shown a decline in pituitary function in soldiers who experienced mild TBI, perhaps due to blast-related trauma.

"We are looking to correlate if there are any pituitary hypofunction and what the effect is on the rest of the body," Riedy said. "We don't know if [the abnormalities] are an indicator of TBI or if they are a clinically relevant finding."

Human consequences

Even though the data fall under the realm of research, the results are shared with all participants, Riedy said.

"For every patient we see, we go over the studies with them carefully," he added. "They are actually making career decisions based on these results. If they see a lot of T2 hyperintensities, many of them are opting for desk jobs instead of redeployment."

He recalled one case in which the results saved a marriage. A wife was ready to divorce her husband because she thought he was exaggerating his symptoms.

"She saw the results of the scan and decided to stay with him and help him through the long recovery process," Riedy said.

The Walter Reed researchers plan to place the accumulated data into a federally funded traumatic brain injury repository where researchers from around the world can access the information.

"We have 20 PhDs looking at this data and we can test a hundred theories or so, but there are people from around the world who have the expertise to bring to bear on this problem," Riedy said. "So we need to give them access to this database so they can share it as well."

'Tip of the spear'

The paper is the second piece of research to come from Walter Reed that shines a light on the effects of TBI in military personnel.

Researchers previously concluded that the sooner a person with a traumatic brain injury receives an MRI scan, the better the chances of finding microbleeds in the brain. Nearly one-quarter of the 603 patients had evidence of cerebral microhemorrhages within three months of their injury, but the number with detected bleeds fell in the months that followed.

"That is the tip of the spear," Riedy said.

He and his colleagues are currently analyzing the data from fMRI and DTI scans taken as part of the current study. Those results will be released in future papers.