A battery of MRI and PET neuroimaging tests show patterns of brain injury in active-duty U.S. soldiers caused by repeated blast exposures, according to a study published April 22 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The findings may guide the design of a new diagnostic test for personnel exposed to blasts in training and combat, noted lead author Natalie Gilmore, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues.

“[Special Operations Forces] personnel may experience cognitive, physical, and psychological symptoms for which the cause is never identified, and they may continue to be exposed to blasts in training or combat during a period of brain vulnerability,” the group wrote.

Currently, there is no diagnostic protocol for detecting brain injury caused by repeated blast exposure, the authors explained. Early detection of these injuries has the potential to enhance the combat readiness of soldiers, their career longevity, and quality of life, they noted.

To advance these efforts, the researchers enrolled 30 active-duty male U.S. Special Operations Forces personnel in the study. The soldiers served in Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, New Dawn, and Inherent Resolve and all had at least a decade of military service with extensive exposure to explosive blasts.

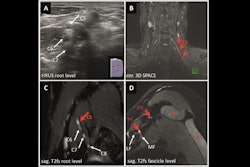

The researchers used advanced neuroimaging methods – structural and diffusion MRI, 7-tesla functional MRI, and hybrid PET/MRI scans – as well as measures of cognitive performance and psychological health to identify potential biomarkers among the group. A board-certified neuroradiologist and neurologist reviewed all conventional brain MRI scans acquired at the study visit, with no acute or chronic traumatic lesions detected for any of the participants.

However, the study analysis revealed that higher blast exposure was associated with increased cortical thickness in the left rostral anterior cingulate cortex, a finding that remained significant after multiple comparison corrections.

“Neuroimaging findings converged on an association between cumulative blast exposure and the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC), a widely connected brain region that modulates cognition and emotion,” the group wrote.

Moreover, while higher blast exposure was associated with worse health-related quality of life, it was not associated with changes in cognitive performance, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, or conventional MRI scans, the researchers wrote.

The authors discussed several limitations, namely the absence of a control cohort in the study. This reflects the challenge of identifying blast-naïve military personnel who perform at the elite cognitive and physical levels of active-duty Special Operations Forces personnel, they wrote.

Ultimately, the work supports the use of a network-based approach focusing on the rACC in future studies. This will involve elucidating the pathophysiological mechanisms and temporal dynamics underlying the associations and their relationship to repeated blast brain injury (rBBI), the authors wrote.

“Future efforts to develop a diagnostic testing protocol for rBBI should consider a network-based approach focusing on the rACC to optimize [Special Operations Forces] brain health,” the researchers concluded.

The full study is available here.