MRI scans of college athletes who have a history of concussion show changes in brain size, blood flow, and structural white matter months and even years after injury, according to a study published online July 21 in the Journal of Neurotrauma.

Nathan Churchill, PhD, from St. Michael's Hospital.

Nathan Churchill, PhD, from St. Michael's Hospital.Researchers from St. Michael's Hospital in Toronto discovered less gray matter and decreased blood flow in the frontal lobe, as well as microstructural changes in white matter, in MRI brain scans acquired nine months to 10 years after injury. No such alterations were seen in MR images of athletes with no previous concussions.

"Looking at this group, we noticed there were strong differences emerging even among people who had not been injured in six months to 10 years," said lead author Nathan Churchill, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Keenan Research Centre at St. Michael's. "The questions are: What does it mean? Does it actually have consequences?"

Concussion concerns

The issue of potentially long-term adverse effects of concussions -- from both sports-related and nonathletic activities -- has received escalating scrutiny among medical researchers. However, as Churchill and colleagues noted, information remains limited on brain abnormalities associated with a history of concussion and how they relate to clinical factors.

There also is speculation that repeated head trauma can lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy and neurodegeneration, including gross cortical atrophy. Somewhat less traumatic, but equally debilitating, can be the loss of cognition and motor skills from long-term changes in brain structure caused by concussions.

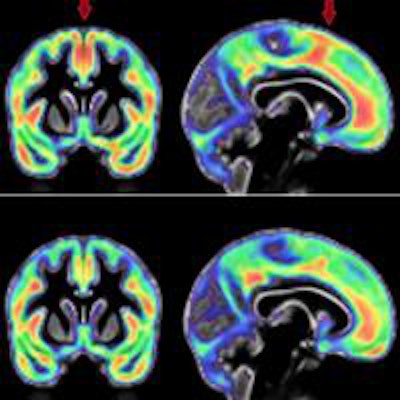

For the current study, the Canadian researchers took a different tack to investigate the long-term effects of concussion by combining scans of cerebral blood flow, gray-matter volume, and white-matter microstructure in one cohort to garner a more comprehensive landscape of the brain. This approach might be the first of its kind for concussion research, Churchill said.

"The vast majority of studies look at only a single measure at one time -- just volumetrics or just blood flow," he added. "We are interested in the convergence across all three measures. For the first time, to our knowledge, we pulled together these different metrics within a single cohort."

The starting lineup

Researchers recruited 43 active athletes between ages 18 and 23 from seven varsity sports (volleyball, hockey, soccer, football, rugby, basketball, and lacrosse) at the University of Toronto, which mandates baseline testing for concussion prior to the start of each season. Thus, the sports medicine clinic at St. Michael's Hospital has a "very high throughput of athletes" from whom researchers can collect detailed clinical data, Churchill said.

MRI brain scans were performed on 21 subjects with a prior history of concussion and 22 athletes with no previously documented concussions. Athletes with a concussion history had a median of two previous head injuries, with a median time of 26 months since their last concussion. The time from their most recent head injury to medical clearance to return to play took an average of 18 days.

Brain imaging was conducted at St. Michael's using a 3-tesla scanner (Magnetom Skyra, Siemens Healthineers) and a standard 20-channel head receiver coil. Among the MRI protocols was a diffusion-tensor MRI sequence to calculate cerebral blood flow, gray-matter volume, white-matter microstructure through fractional anisotrophy, and mean diffusivity.

Brain changes

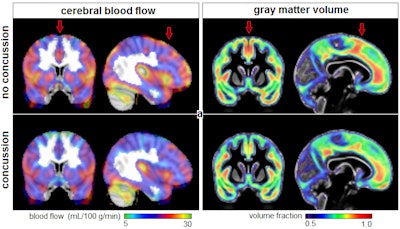

In reviewing the MRI brain scans, researchers discovered that athletes with prior concussions showed a 10% to 20% decrease in gray-matter volume compared with athletes with no concussions. Much of the shrinkage was in the frontal lobes. In addition, they found there was 25% to 35% less blood flow, primarily in the frontal lobes, which are vulnerable to injury because of their location.

"The significance of the changes in the frontal lobe cannot be overstated; this is a critical area of the brain for different processes, [such as] decision-making, planning, and impulse control," Churchill said. "The very fact that this study shows some long-term effects makes it critical to investigate this [finding] in the future as a possible vulnerable area for future injury."

Brain MR images plot the average cerebral blood flow (left panel) and gray-matter volume fraction (right panel) for athletes with and without a history of concussion. Red arrows denote areas where concussed athletes showed significantly lower blood flow and gray-matter volume. Images courtesy of Nathan Churchill, PhD, and St. Michael's Hospital.

Brain MR images plot the average cerebral blood flow (left panel) and gray-matter volume fraction (right panel) for athletes with and without a history of concussion. Red arrows denote areas where concussed athletes showed significantly lower blood flow and gray-matter volume. Images courtesy of Nathan Churchill, PhD, and St. Michael's Hospital.Researchers also found reduced gray-matter volume in the temporal lobes, supplementary motor area, and the anterior cingulate. The deficiencies were associated with a longer recovery time among concussed athletes.

While the causal relationship among changes in gray-matter volume, cerebral blood flow, and white-matter microstructures is not a simple one-to-one corollary, the researchers found common characteristics that were shared among the three variables.

"For example, there are decreases in frontal cortical volume in the same areas there are decreases in blood flow, which speaks to the interesting crosstalk between structure and function in the brain," Churchill said. "But we also see changes that are unique. For example, people who took longer to recover from their last hit had lower blood flow throughout the brain, but the cortical volume itself was not affected."

To a great degree, the findings raise more questions than they answer. So, Churchill and colleagues plan to advance this study.

"In our view, we definitely need more data and need to follow people at multiple time points to see if these brain abnormalities have resolved and look at subjective outcomes," he said. "Do these people tend to have better or worse quality of life? Do they report any problems or symptoms? And what do they look like?"

They also plan to collect more detailed clinical information on the injury locations and the direction of the impacts to see how these factors might play a role in patient recovery time.

This study received funding from Siemens Canada.