MRI scans show that adolescents whose mothers received food enriched with folic acid while they were pregnant have enhanced brain development and a reduced risk of psychosis and other mental illnesses as they progress toward adulthood, according to a study published online July 3 in JAMA Psychiatry.

Researchers discovered different patterns of cortical maturation in children between the ages of 8 and 18 years who were exposed through their mothers to grain products fortified with folic acid. The brain development differences were characterized by significantly thicker brain tissue and delayed thinning of the cerebral cortex in regions associated with schizophrenia.

"The pattern of folic acid exposure in pregnancy slowing the rate of cortical thinning was associated with a reduction in risk for psychotic symptoms in that group," said senior author Dr. Joshua Roffman, an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. "This is the first piece of evidence that ties these folic acid-related brain development changes directly to a clinical feature of mental illnesses. Without that step, it would be hard to know what folic acid exposure-related brain changes might mean for risk."

Folic acid fortification

Beginning in 1996, the U.S. mandated that grain products such as enriched bread, flour, cornmeal, rice, and pasta be fortified with folic acid. The deadline to complete the process was the end of 1997.

Folate is a B vitamin that is found in natural sources such as leafy green vegetables. Folic acid is the synthetic form of folate found in supplements and enriched foods. Because it is not stored in the body, people need to get regular, adequate supplies of the vitamin through their diet or from supplements.

Dr. Joshua Roffman from Harvard Medical School and MGH.

Dr. Joshua Roffman from Harvard Medical School and MGH."It has been known for some time now that for women who have low levels of folic acid in the early stages of their pregnancy, their children are at higher risk for a class of disorders known as neural tube defects," including spina bifida, Roffman told AuntMinnie.com.

Studies from some 20 years ago established that the incidence of spina bifida decreased substantially among children whose mothers took folic acid in the early stages of pregnancy or before they became pregnant, added Roffman, who also serves as co-director of psychiatric neuroimaging at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH).

Fast forward to this decade, and there remains the unanswered question of brain development among fetuses who are exposed to folic acid, compared with development in those who are not, and how that exposure -- or lack thereof -- could influence brain maturation when these individuals grow to adolescence.

It's a difficult question to study, Roffman said, in part because of the time lag between exposure to folic acid during gestation and the development of mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, which tend to appear in late adolescence or early adulthood. In addition, no one has investigated whether folic acid intervention correlates with subsequent brain development.

Among adolescents who develop schizophrenia and school-age children with autism, there is typically an accelerated thinning of the cerebral cortex over childhood and adolescence. Some thinning of the cortex is normal and may relate to synaptic "pruning," during which neurons improve the efficiency of their mutual communication by eliminating unnecessary connections, Roffman said. However, in cases of mental disorders, that thinning process seems to be accelerated.

MRI could provide some answers.

"With MRI, we had the opportunity not only to answer that basic question of whether folic acid exposure alters brain development but also to look at MRI markers of risk for schizophrenia and other serious mental illness," he said.

The researchers reviewed two sets of brain MR images acquired of children and adolescents between the ages of 8 and 18 years who were born between 1993 and 2001. One dataset included normal brain images acquired at MGH as part of the clinical care of 292 patients. The second set consisted of images from 861 participants in the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort (PNC), which included assessments for psychiatric symptoms, including psychotic disorders (JAMA Psychiatry, July 3, 2018).

To confirm the cortical thinning effects related to folic acid, the researchers relied on a third set of 217 participants from a multisite study conducted by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). This group included children 8 to 18 years old who were imaged before folic acid fortification.

Roffman and colleagues divided the subjects by birth date, based on whether they were born before, during, or after the implementation of folic acid fortification. They then correlated cortical thickness in the brains of the adolescents with their exposure to folic acid during gestation. The final sample included 217 participants and a total of 383 MRI scans on either 1.5-tesla or 3-tesla systems.

Brain alterations

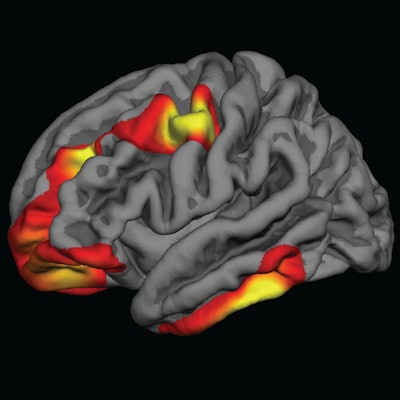

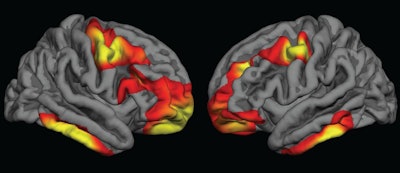

The researchers observed cortical thickness in the bilateral frontal and inferior temporal regions of the brain in adolescents who were exposed to folic acid compared with those who were not. For children born during the fortification period, partial folic acid exposure had more "intermediate effects," they noted.

The differences were characterized by significantly thicker brain tissue and delayed thinning of the cerebral cortex in regions associated with schizophrenia.

Colored areas indicate regions of the cerebral cortex that are significantly thicker in children who were exposed to folic acid fortification during pregnancy, compared with those who were not exposed. Images courtesy of Dr. Joshua Roffman.

Colored areas indicate regions of the cerebral cortex that are significantly thicker in children who were exposed to folic acid fortification during pregnancy, compared with those who were not exposed. Images courtesy of Dr. Joshua Roffman.Within the MGH cohort of normal brain scans, the researchers "observed widespread increases in frontal and temporal cortical thickness between comparable groups of youths who gestated just after, compared with just before, the rollout of folic acid fortification," they wrote. "Youths who gestated during the [folic acid] rollout, and who therefore had partial exposure, demonstrated intermediate increases, consistent with a dose association."

Results from the PNC subjects were similar to those in the MGH adolescents, with individuals exposed to folic acid fortification showing signs of delayed cortical thinning of similar duration in the frontal, temporal, and parietal regions.

Age factor

The researchers also found cortical thickness differences based on age, especially in the left inferior temporal and inferior parietal regions where there was a delay in age-associated cortical thinning.

"In the first few years, 8 to 11 years old, we saw the strongest differences in cortical thickness between the exposed and unexposed groups," Roffman said. "Over time, as they approached age 18, those differences tended to diminish."

Why was the effect more pronounced in younger kids? He suggested that the finding may be related to schizophrenia's strong genetic link in which first-degree relatives have a much greater risk of developing the disorder than the general population.

Roffman and colleagues noted a few limitations of the study, including its retrospective approach. The researchers also could not rule out how different magnetic field strengths within the MGH cohort may have affected the results.

"Although we use the fortification rollout as the proxy for increased folic acid, the most definitive way to study this [question] would be to have a large prospective cohort where we have a turnover of folic acid levels, if [mothers] take prenatal vitamins in addition to fortification, and then look longitudinally at the kids as they develop over time," Roffman said. "That is a long study to do because you have to start before birth and continue through the greatest risk of these disorders, which can be two decades."

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)