Despite bans on leaded gasoline and lead-based paint, areas of high lead exposure still exist. MR images have helped uncover differences in brain structure and subsequently lower cognitive performances in children living in areas with these toxic conditions, according to a study published January 13 in Nature Medicine.

The findings come from data in the ongoing, 10-year longitudinal Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. Researchers from Children's Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California (USC) found that children most affected by lead exposure came from lower-income families. MRI scans showed that these kids exhibited less cortical volume, smaller cortical surface areas, and lower cognitive test scores than children from high-income families whose children also were exposed to lead.

"It is important to note that causality cannot be inferred because of the cross-sectional, observational nature of the ABCD study's baseline data and because we do not currently have direct data on participants' lead exposure levels," wrote the authors, led by Elizabeth Sewell, PhD, a professor of pediatrics at USC. "However, our results suggest that U.S. children from low-income families might be more vulnerable to environmental insults associated with high risks of lead exposure."

It is well-known that socioeconomic factors such as family income can have a positive influence on brain development and cognitive functioning. Total brain volume also is associated with intelligence. Consequently, children from higher-income families tend to have significantly larger volumes of gray matter than children from lower-income households. Previous studies, however, have not taken into account to what degree children from different levels of affluence are subjected to lead.

"Thus, the neurotoxic effects of lead exposure may be exacerbated in low-income children, who may have less access to environmental enrichment," Sewell and colleagues added.

To further investigate the issue, the researchers analyzed 9,712 children in the ABCD study. Of that cohort, 5,745 (60%) children lived in areas classified by the researchers as at intermediate-risk (33%) for lead exposure, while another 2,657 children (27%) resided in high-risk areas. The children underwent structural MRI scans, which included T1- and T2-weighted imaging sequences for the purpose of the study.

Sewell and colleagues found that among children with the highest risk level of lead exposure (lead risk = 10), children from low-income families achieved 12.2% lower total cognitive test scores, had 9.6% smaller cortical volumes, and had 8.2% smaller cortical surface area than the children from high-income families who also were living in the highest-risk neighborhoods.

The differences between the two income groups lessened as their respective levels of lead exposure decreased. For example, at a lead risk level of 1, the difference in cognitive scores was only 4.2%, the difference in cortical volume was 2.9%, and the difference cortical surface area was narrowed to 2.3%.

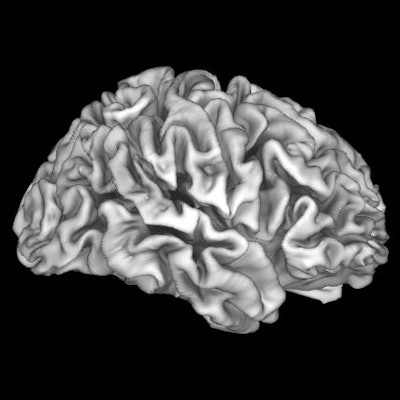

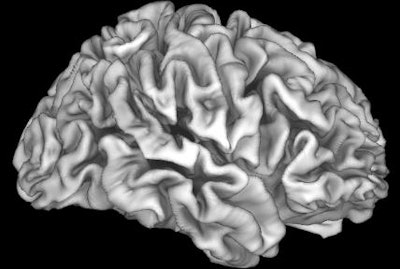

Brain MR image shows that the cortex is adversely affected by the high risk of lead exposure in children from lower-income families. Images courtesy of Marshal et al and Children's Hospital Los Angeles.

Brain MR image shows that the cortex is adversely affected by the high risk of lead exposure in children from lower-income families. Images courtesy of Marshal et al and Children's Hospital Los Angeles."What we're seeing here is that there are more pronounced relationships between brain structure and cognition when individuals are exposed to challenges like low income or risk of lead exposure," noted lead study author Andrew Marshall, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at USC, in a statement.

The authors recommended additional studies to determine the precise cause for these differences to determine if lead exposure itself or other factors associated with living in a high lead-risk environment contribute to the results.