Using functional MRI (fMRI) to gauge a child's neurological responses to different visual stimuli, researchers believe they have developed a faster way to diagnose autism, according to a study in the current online edition of Biological Psychology.

Their approach targets the ventral medial prefrontal cortex, which helps process decision-making. Among the autistic children in this study, the average response in this brain region to familiar faces was significantly diminished, compared with a group of typically developing children. Using fMRI to diagnose autism could take a fraction of the time required for more conventional methods.

"These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the brains of children with autism spectrum disorder do not encode the value of social exchange in the same manner as typically developing children," wrote lead co-authors Kenneth Kishida, PhD, from Wake Forest School of Medicine and Dr. Josepheen De Asis-Cruz, PhD, from Children's National Health System and colleagues. "The latter finding suggests the possibility of utilizing single-stimulus fMRI as a potential biologically based diagnostic tool to augment traditional clinical approaches."

Currently, it takes two to four hours for a clinician to diagnose autism, with much of the conclusion based on a subjective analysis. With the fMRI-based approach, researchers are looking to create a more rapid, objective measurement of an autistic child's brain by comparing its response to different stimuli and using that result as a biomarker for autism.

For this study, the researchers looked at 44 typically developing children and 24 children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Functional MRI scans were performed on two 3-tesla MRI scanners (Allegra and Trio, Siemens Healthineers). The researchers targeted the brain's ventral medial prefrontal cortex based on previous studies that showed the region's role in "encoding the value of different types of reward" and as a "critical component of reward processing and decision-making in humans," the authors wrote (Biol Psychol, July 2019, Vol. 145, pp. 174-184).

The first phase of the study had the subjects view eight images for five seconds each of either a favorite person or favorite object during the 12- to 15-minute fMRI exam. The set was repeated six times in random order and included two pictures chosen by the subject. The other six pictures included three faces and three objects, each of which were designed to appear as pleasant, neutral, or unpleasant based on previously published psychological experiments.

The 12- to 15-minute fMRI scan was followed by two behavioral tests. The children viewed the images on a computer screen and ranked them on a sliding scale from pleasant to unpleasant. They also were asked to look at pairs of images and decide which image they liked better.

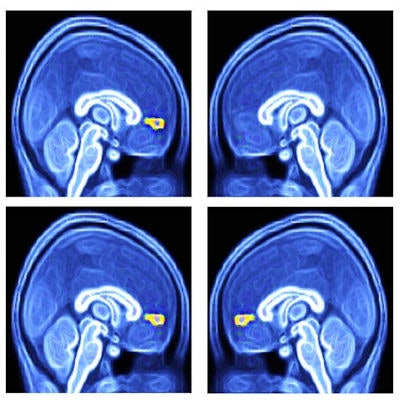

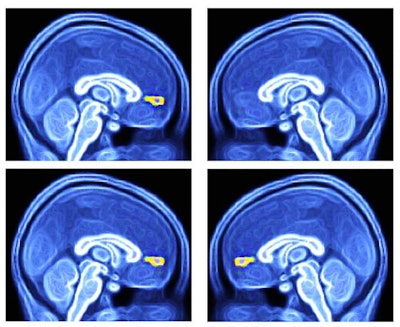

As the researchers had hypothesized, the functional MR images showed that the average response of the ventral medial prefrontal cortex was significantly lower in the autistic group than among typically developing subjects. That dysfunction related to the autistic children's reduced ability to process their self-chosen favorite faces but not favorite objects.

Among children with ASD, the brain's ventral medial prefrontal cortex (yellow) activates normally when they view their favorite objects but does not respond (top right, missing yellow) when they see their favorite faces. Among typically developing children, the region reacts normally (bottom left and right, yellow) to seeing favorite faces and objects. Images courtesy of Wake Forest Baptist Health.

Among children with ASD, the brain's ventral medial prefrontal cortex (yellow) activates normally when they view their favorite objects but does not respond (top right, missing yellow) when they see their favorite faces. Among typically developing children, the region reacts normally (bottom left and right, yellow) to seeing favorite faces and objects. Images courtesy of Wake Forest Baptist Health."Our results suggest that perturbed valuation of social rewards in the ventral medial prefrontal cortex contributes to the impairments observed in autism: social stimuli are devalued, leading to decreased motivation to seek such rewards," the authors wrote. Simply put, the autistic subjects could not encode the value of social exchange in the same way as typically developing children.

Kishida and colleagues plan to advance their research to determine which additional areas of the brain might be involved in the different facets of autism to help personalize treatments for the children.