To evaluate large-vessel vasculitis (LVV), two modalities are better than one. A dual-modality approach worked well for French researchers who combined PET and MRI to improve their analysis of vasculitis abnormalities in a study published August 27 in Scientific Reports.

By merging contrast-enhanced anatomic assessments of MRI with the quantitative measurement of FDG uptake in PET, the researchers were able to accurately characterize and differentiate between inflammation and fibrosis in the aortic walls and auxiliary branches. Information gleaned from the hybrid modality could help direct clinicians to more appropriate treatment for patients with large-vessel vasculitis and reduce the need for temporal artery biopsies.

"In LVV imaging, combining different morphological parameters (wall thickening, enhancement) with biological parameters (FDG glucose metabolism) can assist in the characterization of disease status," wrote the researchers, led by Dr. Charlotte Laurent, from Sorbonne University and Hospital Saint-Antoine in Paris (Sci Rep, August 27, 2019). "Moreover, the simultaneous acquisition of PET and MRI data offers good colocalization of anatomic structures and the biological process occurring within these structures."

LVV's challenges

Large-vessel vasculitis is characterized by inflammation in the walls of the aorta, or aortitis, and its main branches, which can result in stenosis and aneurysms. The two main forms of the condition are giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu's arteritis (TA). In both cases, their diagnoses can be difficult, especially in patients who present with GCA symptoms but have negative results on temporal artery biopsies.

"In these patients, it is necessary to demonstrate arterial involvement in order to confirm the diagnosis of GCA," the authors noted. "In TA, the assessment of disease activity can be challenging, and PET imaging can be useful to distinguish fibrotic stenosis from active arterial lesions."

How PET/MRI might help in this regard is still unknown, as very few studies have investigated the hybrid modality for this clinical application. One 2019 retrospective study by Einspieler et al analyzed 14 patients with aortitis and 14 patients without the condition. The researchers used FDG-PET and pre- and postcontrast 3-tesla MRI with a T1-weighted volumetric interpolated breath-hold exam (VIBE) sequence to compare the two imaging strategies to evaluate aortic inflammation. They found a comparable number of patients with aorta vessel wall inflammation in patients with large-vessel vasculitis with MRI as they did with FDG-PET.

With those encouraging findings, Laurent and colleagues took the next progressive step to determine the efficacy of the hybrid modality for diagnosing the condition and patient follow-up by integrating the findings with two imaging patterns to determine LVV status.

Inflammation and fibrosis

Their study included 13 consecutive patients (median age, 67 years; range, 23-87 years), who underwent a total of 18 PET/MRI scans (10 exams for Takayasu's arteritis and eight scans for giant cell arteritis). PET/MRI scans were performed with a hybrid system (Signa PET/MRI, GE Healthcare) to allow for simultaneous acquisition of PET and 3-tesla MR images. Four scans were performed at diagnosis, seven scans to determine if patients had relapsed, and seven scans conducted during remission.

The median time between diagnosis to the scans was 44 months (range, 0-222 months), with a mean of 14 months (range, 0-61 months) for GCA patients and a median of 86 months (range, 4-222 months) for TA patients.

PET images were interpreted for FDG uptake to signal inflammation, while delayed-enhancement MR images were reviewed to determine any thickening of the aortic wall and luminal narrowing and dilation. The researchers targeted 11 arterial segments: four aortic segments, right and left common carotid arteries, right and left subclavian arteries,vertebral arteries, and common iliac and femoral arteries. Within those segments, they looked for three particular patterns in the PET/MRI results:

- Inflammatory patterns with positive FDG uptake in PET images and abnormal MRI with stenosis and/or wall thickening

- Fibrosis patterns with negative FDG uptake in PET images and abnormal MRI stenosis and/or wall thickening

- Normal patterns with negative results in both modalities

Abnormal patterns

Among the 18 PET/MRI scans, Laurent and colleagues observed an inflammatory pattern in eight results (44%) and a fibrous pattern in three cases (17%). The remaining seven scans (39%) were normal.

When the researchers compared the 10 PET/MRI scans performed on the six TA patients, they discovered an inflammatory pattern in all five patients (100%) with active TA. Only two (20%) of the PET/MRI scans were normal. Among the seven GCA patients who underwent a total of eight PET/MRI scans, inflammation was found in three (50%) of the six patients with active GCA. The hybrid modality also uncovered vascular signs in four (80%) of the five active TA patients and three (50%) of the six GCA patients.

"The inflammatory pattern, defined as both abnormal PET and MRI, was highly associated with disease activity, particularly in TA," the study authors noted. "This pattern was found in all scans from patients with active TA disease, compared to only 50% of scans from patient with active GCA."

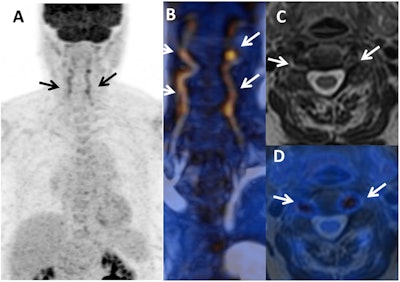

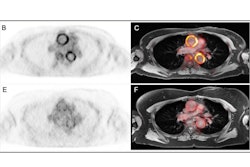

PET and MR images show the initial diagnosis of giant cell arteritis (GCA) in a female with temporal headaches and acute-phase proteins that can cause inflammation but no vascular signs or join pain (arthralgia). There is an inflammatory pattern with clear FDG uptake in vertebral arteries in maximum intensity projection (A) and fusion MR angiography/PET (B) (arrows), which is associated with arterial wall thickening on axial T2-weighted MR image (C) and T2-weighted/PET fusion (D). Images courtesy of Scientific Reports.

PET and MR images show the initial diagnosis of giant cell arteritis (GCA) in a female with temporal headaches and acute-phase proteins that can cause inflammation but no vascular signs or join pain (arthralgia). There is an inflammatory pattern with clear FDG uptake in vertebral arteries in maximum intensity projection (A) and fusion MR angiography/PET (B) (arrows), which is associated with arterial wall thickening on axial T2-weighted MR image (C) and T2-weighted/PET fusion (D). Images courtesy of Scientific Reports.Clinical benefits

Beyond the accurate evaluation of aortitis, pairing MRI with PET instead of CT can "reduce the radiation dose to the patient, thus facilitating repeated use for patients, if necessary, to evaluate the disease activity during follow-up," Laurent and colleagues wrote. "In GCA, repeated PET/MRI could help to confirm clinical relapse, and in TA, repeated PET/MRI could be used to determine remission and absence of arterial progression."

The additional information on the composition of aortitis from PET/MRI also could reduce the need for temporal artery biopsy. It would be a welcome omission in GCA cases, given that previous studies have pegged the procedure's false-negative rate between 6% and 17%, especially if a sample is taken from an arterial segment with no signs of the condition.

"By increasing the sensitivity for the detection of vasculitis using digital PET detectors and integrated PET/MRI analysis, the use of invasive tests, such as temporal artery biopsy, may not be necessary," the authors concluded.

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)