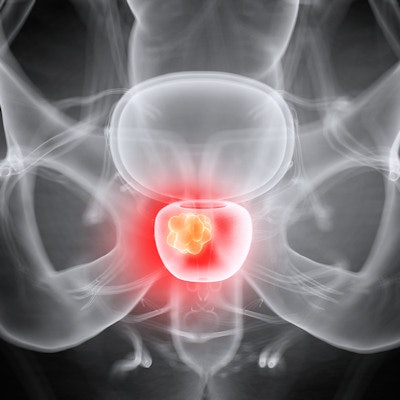

MRI-targeted biopsy can greatly improve prostate cancer diagnosis and reduce the chances of patients being either overtreated or undertreated for their disease, according to a study published March 5 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

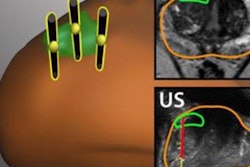

MRI-targeted biopsies combine MR images of suspected cancer with real-time ultrasound. In the new study, the technique discovered approximately 10% more prostate cancers than systematic biopsy alone and upgraded or changed 22% of more than 2,100 cases to a more aggressive forms of the disease, according to researchers from the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI).

"Prostate cancer has been one of the only solid tumors diagnosed by performing systematic biopsies 'blind' to the cancer's location," said senior author Dr. Peter Pinto, from the NCI's Center for Cancer Research, in a statement. "With the addition of MRI-targeted biopsy to systematic biopsy, we can now identify the most lethal cancers within the prostate earlier, providing patients the potential for better treatment before the cancers spread."

Prostate cancer varies widely in severity and can easily metastasize to other parts of the body. While low-grade prostate cancer is associated with a very low risk of death and often does not require treatment, high-grade prostate cancer is much more likely to spread and greatly reduce a patient's chances for survival.

Pinto and several NIH colleagues first developed MRI-targeted biopsies more than 10 years ago, and they worked with Philips Healthcare to develop software designed to overlay MR images onto ultrasound in real-time to provide a view of lesions from which samples could be taken. It was a task not possible solely with systematic biopsy, which is a considerably less direct method of locating and sampling suspected cancerous lesions and naturally is prone to miss more severe cancer.

"For decades [systematic biopsy] has led to the overdiagnosis and subsequent unnecessary treatment of nonlethal cancers, as well as missing aggressive high-grade cancers and their opportunity for cure," Pinto noted.

To determine the efficacy of MRI-targeted biopsy, Pinto and colleagues analyzed 2,103 men with lesions visible on MRI who underwent both MRI-targeted and systematic biopsies. Of those subjects, 1,312 men (62%) were diagnosed with cancer and 404 (19%) of them underwent prostatectomy.

In the direct comparison of diagnoses, the researchers found that MRI-targeted biopsy resulted in 208 more cancer diagnoses (10%) than systematic biopsy alone and led to 458 upgrades (22%) or changes in diagnosis to a more aggressive cancer, based on analysis of the biopsy tissue by histopathology.

In addition, among the men who underwent prostatectomy, MRI-targeted biopsies underdiagnosed fewer cancers (30%), compared with systematic biopsy alone, which underdiagnosed approximately 40%. When the two approaches were combined, underdiagnosed cases decreased to 14% of the cancers.

For the most aggressive prostate cancer cases, systematic biopsy underdiagnosed 17% of the patients, compared with 9% of those cases with MRI-targeted biopsy. When combined, the modalities only missed 3.5% of the most aggressive cancers.

"Seeing this technology really make a difference in how we diagnose and treat prostate cancer is validation of the work we have done and continue to do at NIH," Pinto stated. "But the change that matters most to us is how this impacts the patients we see every day, for whom we can now make more informed treatment decisions."