Functional MRI (fMRI) shows that damage to white matter in the brain leads to worse long-term cognitive health outcomes than damage to gray matter does, according to a study published May 11 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

The results could help clinicians better predict the long-term effects of strokes and other traumatic brain injury, according to a team that included senior author Dr. Aaron Boes, PhD, of the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

"These findings might help us better predict, based on the location of the damage, which patients are at risk for cognitive impairment after stroke or other brain injury," Boes said in a statement released by the university. "It's better to know those things in advance as it gives patients and family members a more realistic prognosis and helps target rehabilitation more effectively."

A research group led by first author Justin Reber, PhD, also of the University of Iowa, analyzed fMRI scans and results from cognitive function tests from more than 500 people with brain damage caused by stroke or other injury. Patient data came from two sources: Washington University in St. Louis, which provided information from 102 patients, and the Iowa Neurological Registry, which provided information from 402 patients.

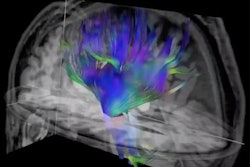

The researchers used fMRI to track the location of the damage and assess whether there were links between the damaged areas and cognitive disability, particularly using a measure called edge density (i.e., tracking the density of white-matter connections that form highly connected "hubs" in the brain).

To their surprise, the investigators found that lesions "disrupting white-matter regions with high edge density were associated with cognitive impairment, whereas lesions damaging gray-matter regions with high participation coefficient had a weaker, less consistent association with [poor] cognitive outcomes."

"The most unexpected aspect of our findings was that damage to gray-matter hubs of the brain that are really interconnected with other regions didn't really tell us much about how poorly people would do on cognitive tests after brain damage," Reber said in the university statement. "On the other hand, people with damage to the densest white-matter connections did much worse on those tests ... This study is a reminder that connections between brain regions might matter just as much as those regions themselves, if not more so."

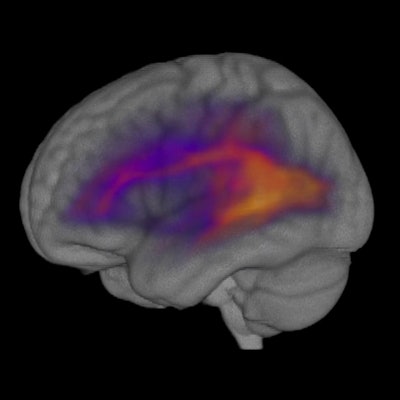

Using diffusion-weighted imaging and structural MRIs, the researchers created a map to measure the density of white-matter connections between different brain regions. The color scale in this video goes from dark purple where there are only sparse connections to a yellowish white where the connections are most densely packed. A University of Iowa study suggests that damage to highly connected regions of white matter is more predictive of cognitive impairment than damage to highly connected gray-matter hubs. Video courtesy of Justin Reber, PhD, University of Iowa.

The results suggest that further exploration of "how focal brain lesions influence cognition" is needed, according to the authors.

"Our findings indicate that edge density can be used to predict the likelihood of cognitive impairments, above and beyond the predictive utility of well-established predictors like lesion volume," the group concluded. "As such, this information could be incorporated into prognostic tools to more accurately predict cognitive outcomes after an acquired brain lesion, helping to inform treatment and rehabilitation plans for patients with focal brain damage."