Cardiac MRI has overcome issues that limited its use in the past. But challenges remain, specifically in how it can diagnose cardiovascular disease (CVD) in women, according to a presentation May 9 at the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) meeting.

In a plenary session Monday afternoon in London, Dr. Warren Manning, chief of noninvasive cardiac imaging at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, discussed paradigm shifts in the development of cardiac MRI (CMR) over the past 30 years.

ISMRM is holding this week's meeting in conjunction with the European Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine and Biology and the International Society for MR Radiographers and Technologists.

How cardiac MRI applies to women

Manning was followed during the session by Dr. Mona Bhatia, head of cardiac imaging at Fortis Escorts Heart Institute in New Delhi, India, who discussed how current cardiac MRI techniques apply uniquely to women.

"I think of noninvasive cardiac imaging as a funnel through which all of our patients pass on their way to a diagnosis, or for monitoring for patients who are getting therapy," Manning said, in the introduction to his talk.

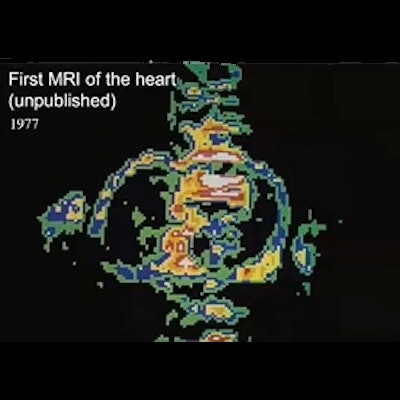

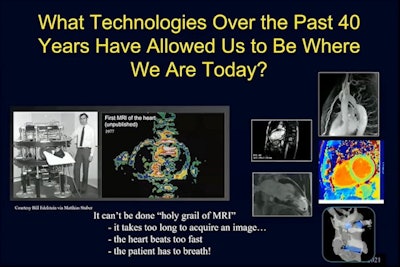

In the beginning, however, there was doubt. "People said, 'oh, you can't do the heart, the heart is the holy grail of MR,' " Manning said.

One of the most significant articles published in the past 30 years in the field concerned the use of contrast-enhanced MRI to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction, Manning said. This led to the observation that gadolinium was actually retained in the myocardium and helped establish a technique called late gadolinium enhancement (LGE).

LGE was the first "killer app," in cardiac MRI and is widely used today for cardiac tissue characterization, especially for the assessment of myocardial scar formation and regional myocardial fibrosis, Manning said.

A major next step was the development of balanced steady-state free precession (SSFP), a technique pioneered by researchers at Siemens Healthineers that offers a very high signal-to-noise ratio. Prior to this development, clinicians had difficulty seeing ventricular endocardial borders, especially in patients who had poor cardiac output, Manning said.

"Quickly, almost overnight, it became the standard way we acquire images, and it is still used today -- a fundamental advance in cardiac MR," he said.

This development was followed by techniques for faster image acquisitions and more recently by parametric mapping, which provides direct visualization of tissue MRI properties and a more complete assessment of the myocardium.

Today, when these techniques are put together, they can offer a "30-minute cardiac CMR for common clinical indications," an exam recently outlined in a white paper from the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, Manning noted.

In the conclusion to his talk, Manning said present advantages to cardiac MRI include the use of nonionizing radiation, excellent soft-tissue contrast, 3D acquisition of complex structures, high temporal resolution, and superior image quality and perfusion assessment.

"We take these beautiful images we have today for granted," he concluded.

Cardiac MRI for women

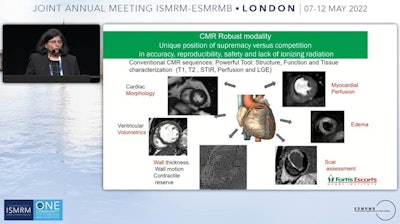

Following Manning's presentation, Bhatia of Fortis Escorts Heart Institute agreed that cardiac MRI is an extremely robust modality with a unique position of supremacy in accuracy, reproducibility, safety, and for its lack of ionizing radiation.

However, she noted that CVD affects women differently, and thus women require different imaging approaches to diagnose disease.

CVD accounts for one female death every 90 seconds, Bhatia said. Despite increasing awareness, in the last decade CVD mortality has been rising in younger women who continue to receive less timely, aggressive, and appropriate diagnoses and treatment than men, she said.

"With this super toolbox we have for cardiac MR, why are we still lagging behind on the women's story?" she asked.

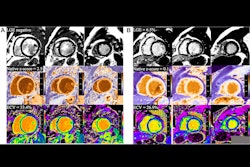

One issue is that quantitative cardiac MRI normative values and cut-offs used for males do not hold true for females, Bhatia said.

For instance, ventricular volumetrics studies have shown that women in fact have smaller hearts. Left ventricles (LV) and right ventricles are smaller in terms of end-diastolic and systolic volumes, and stroke volumes, compared with men, Bhatia said. Men also have a greater absolute and indexed LV mass.

When looking at age-specific ventricular reference ranges, LV volume and mass decrease with age for men, while women have an adaptive response and see increases in LV volume with age. In addition, parametric T1 mapping has shown that native T1 and extracellular volume fraction (ECV, a marker of myocardial tissue remodeling) are higher in women, Bhatia said.

Awareness of these differences between men and women can have a huge impact in clinical diagnoses of CVD, and Bhatia summed up normative values among women as follows:

- Smaller ventricular volumes

- Lower ventricular mass

- Greater LV torsion, ejection fraction, and strain

- Higher native T1 and ECV

On top of these differences, multiple other factors have additional impact on inducing sex-specific responses to cardiovascular injuries, such as anatomical and physiological differences, sex hormones, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause, Bhatia added.

"We have a challenging jigsaw and CMR is the critical piece for patient satisfaction and patient management," she noted.

Ultimately, more research is required to continue raising the bar.

"We definitely need to have a global concerted and targeted effort with a fair representation of women in larger studies today for adequate consideration of sex-specific data," Bhatia concluded.