MRI used with a machine-learning model shows that people with compromised heart health in their 30s are at risk for premature brain aging as they enter their golden years, a study published August 22 in the Lancet Healthy Longevity has found.

Tracking brain health via MRI and machine learning in those who have had poor cardiovascular health earlier in life could offer a way to not only predict how an individual may age but also help tailor prevention of and treatment for neurodegenerative disease, according to lead author Dr. Jonathan Schott of University College London's Dementia Research Centre in the U.K.

"We hope this technique [of using MRI with machine learning] could one day be a useful tool for identifying people at risk of accelerated aging, so that they may be offered early, targeted prevention strategies to improve their brain health," Schott said in a statement released by the university.

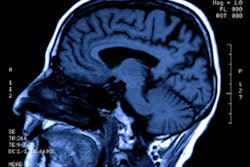

Brain age and cardiovascular health have been linked before, and older brain age compared with chronological age is associated with worse scores on cognitive tests and risk of increased brain atrophy over time -- which suggests that it "could be an important clinical marker for people at risk of cognitive decline or other brain-related ill health," the journal said in a statement.

Schott's team sought to explore possible connections between older brain age and poorer cardiovascular health via a study that used an MRI-based machine learning algorithm to assess the brain age of 456 British people born in a single week in 1946.

The study participants were part of the U.K.'s Medical Research Council National Survey of Health and Development study (also known as the 1946 British Birth Cohort or Insight 46), which tracked them their entire lives. As part of the study, they have undergone 24 health assessments, including heart health assessment with the Framingham Heart Study Cardiovascular Risk Score.

All participants also received MRI exams between May 2015 and January 2018, when they were between the ages of 69 and 72.

The machine-learning model Schott and colleagues created was trained on 2,001 healthy adults between the ages of 18 and 90. The group used this model to compare the Insight 46 MRI exam data to the chronological age of study participants to determine what they call the "brain-predicted age difference."

Schott's team found that those study participants who had worse heart health in their 30s also had worse brain health in their late 60s and early 70s, and that increased brain-predicted age was associated with increased cerebrovascular disease burden, lower cognitive performance, and increased serum neurofilament light concentration (a biomarker for neuronal injury).

The investigators also found that the model predicted the brain ages of women to be five years younger than those of men. But the researchers did not find any association between higher brain age compared to chronological age based on childhood cognitive ability, educational level, or socioeconomic class.

The study results suggest that brain-predicted age difference based on MRI findings could be a useful way to assess an individual's brain health, according to the authors.

"These findings support brain-predicted age difference as an integrative summary metric of brain health, reflecting multiple contributions to brain aging, and which might have prognostic utility," they concluded.