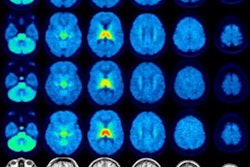

Brain signals detected on functional MRI during eating may be diminished in people with obesity, and these impaired responses appear to persist even after weight loss, according to a group at Yale University.

Researchers led by endocrinologist Mireille Serlie, MD, PhD, studied functional MRI (fMRI) signals in lean people and people with obesity after they were infused with glucose or fat directly into the stomach. A comparison revealed reduced neuronal activity in obese patients in the striatum, which plays an essential role in regulating eating behavior, according to the group.

"This was surprising," said Serlie, in a news release from the university. "We thought there would be different responses between lean people and people with obesity, but we didn't expect this lack of changes in brain activity in people with obesity."

So-called "post-ingestive nutrient signals" to the brain regulate eating behavior in rodents, and impaired responses to these signals have been associated with pathological feeding behavior and obesity, the researchers explained. To assess this in humans, Serlie's group performed a clinical study that included 30 women with a healthy body weight (12) and 30 with obesity (18). The women underwent fMRI to study cerebral neuronal activity based on blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals, with lower signals in regions of interest (ROIs) indicating reduced neuronal activity.

According to a whole-brain voxel-wise analysis of fMRI scans acquired 10 to 15 minutes after the nutrient infusions, obese patients had reduced BOLD signals in ROIs including the striatal, frontal, insular, limbic, occipital, parietal, and temporal brain regions.

Next, participants with obesity underwent a 12-week dietary weight-loss program, with those who lost at least 10% of their body weight undergoing a second round of imaging. For these individuals, weight loss did nothing to change the brain's response, according to the researchers.

"We show that a 12-week supervised dietary intervention promotes significant weight loss and metabolic improvement, but does not restore the physiological brain response to post-ingestive glucose or lipids in humans with obesity," they stated.

These differences in brain activity could help explain why it's difficult for some people to lose weight and maintain weight loss, according to the group.

"Given the devastating impact of obesity worldwide, it is highly relevant to determine whether post-ingestive nutrient signals ... are impaired in humans with obesity," the researchers wrote.

This research is still in its early stages, Serlie noted, and said that more research will be needed to uncover why diminished nutrient sensing occurs in some people, what biological pathways are involved, and when these changes begin to take hold.

The study was published online June 12 in Nature Metabolism.

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)