Physicians should be on the lookout for potential neurologic side effects related to new Alzheimer's disease treatments, according to a study published August 31 in RadioGraphics.

A group led by Amit Agarwal, MD, of Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, reviewed evidence from clinical trials testing new monoclonal antibodies for the disease and noted major neurologic safety concerns related to the medications: namely, amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA).

"For radiologists, knowledge about the imaging findings of ARIA and the imaging protocol is essential, as the volume of treatment-monitoring MRI examinations is expected to grow exponentially over the next decade," the group wrote.

Disease-modifying drugs like Leqembi and Aduhelm are monoclonal antibodies that work by clearing toxic beta-amyloid protein from the brain. These deposits are thought to trigger the development of tau protein, which is associated with cognitive decline in patients.

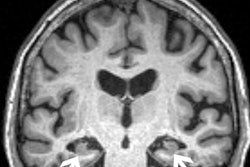

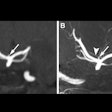

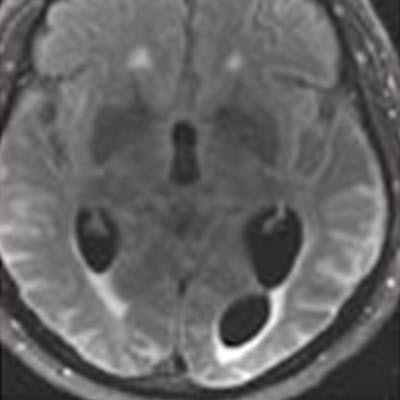

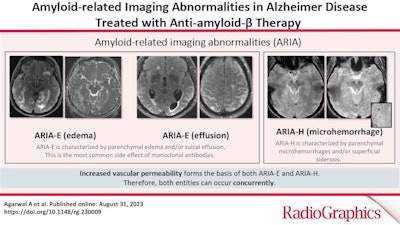

In fact, the increased use of these treatments in trials led to the discovery of ARIAs, the authors noted, and they have since been further classified into two categories, ARIA-E, representing edema (swelling) and/or effusion, and ARIA-H, representing hemorrhage. Both are thought to be caused by increased vascular permeability following an inflammatory response, leading to the leakage of blood products and fluid into surrounding tissues.

Patients with ARIA sometimes have headaches, but they are usually asymptomatic and only diagnosable with MRI, the authors wrote.

In the study, Agarwal and colleagues found that in two phase III trials, 35% of patients on the approved dose had ARIA-E. These trials also showed that most ARIA-E cases were clinically asymptomatic and that 98% were resolved at follow-up imaging. ARIA-E occurred most frequently between three and six months of treatment, with incidence sharply dropping after the first nine months, the authors noted.

A graphical abstract.

A graphical abstract.ARIA-H typically occurs in about 15% to 20% of patients treated with monoclonal antibodies and unlike ARIA-E, ARIA-H is not transient and does not resolve over time, they found.

"It is essential for the radiologist to recognize and monitor ARIA," Agarwal said, in a news release from RSNA.

Most patients with asymptomatic ARIA who meet specific radiographic and clinical criteria may continue to receive treatment, Agarwal advised. The vast majority of patients with ARIA-E can continue therapy either with or without temporary suspension; however, in ARIA-H patients, therapy decisions depend on the severity of ARIA-H and whether it is stabilized. The detection of 10 or more new microhemorrhages requires permanent discontinuation of therapy, he said.

"Immunotherapy is becoming more prevalent in managing dementia, and the recently approved monoclonal antibody therapy offers an exciting new frontier," Agarwal said. "Identifying and monitoring ARIA plays a vital role in safety monitoring and management decisions in anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody trials and clinical practice."

Ultimately, when ARIA is present, a conservative monitoring plan should be established with a multidisciplinary approach that includes neurologists and radiologists familiar with the clinical and imaging aspects of the condition, the researchers concluded.

The full article is available here.